Abstract

Monuments listed in UNESCO’s Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Site suffered massive, disastrous damage when struck by the Gorkha earthquake in 2015, and Nepal undertook a massive program of ‘reconstructive conservation’ stretching over six years. This article reviews a select number of such monument reconstruction projects to evaluate the processes, materials and methods used and assess their response to create and gain authenticity, integrity and values in line of the traditionally followed reconstructive conservation in recorded to have been in practice in Nepal over its long history and argues that success of some of the reviewed projects deserves to be praised for making the best coming out of the disaster. The articles also review the reconstructive conservation experiences of Nepal in modern times (1950-2015) as a prelude to understanding the nature of Nepal’s post-earthquake reconstruction process and its buildup of mixed stance in choosing between the traditional and the modern options and approaches. It concludes that some of the projects make excellent cases for study as creative exercises in reconstructive conservation and as a positive theoretical contribution to the field.

Keywords: Kathmandu Valley World Heritage, Reconstruction, Post-Earthquake Reconstructive Conservation, Traditional Materials, Technology and Processes, Authenticity

Introduction and Prior Learnings in Contemporary Restoration:

The unique brick, wood and tile architecture and the urbanscape of the central palace core of settlements of Kathmandu Valley have held the world captivated ever since Nepal opened up to the outside world from its century-old self-imposed political seclusion in 1951. The Department of Archaeology was set up in 1953 and the Nepal Ancient Monuments Act, modeled after similar Indian legal instruments, came into force in 1956. World interest in saving and supporting the maintenance of this medieval-built culture grew also as Nepal started receiving technical assistance and experts under the United Nations development programs. In the early 1970s, Nepal got the Kathmandu Valley Inventory (of heritage) as well as the Masterplan for the Conservation of the Cultural Heritage of the Kathmandu Valley prepared as outcomes of UN-sponsored assistance. The complexity of the problem of conservation of the cultural heritage of Kathmandu had thus beenstudied and the basic principles were set out early enough. Nepal’s sincerity towards the preservation and protection of its heritage and its willingness to learn from Western experiences is well expressed in these documents prepared even as the idea of World Heritage was shaping up under UNESCO.

Kathmandu Valley Heritage was the first applicant seeking listing as World Heritage in 1977 and highlighted the eagerness of the experts involved in its identification and development of protection plans. Its incorporation as WHS was approved in 1979. Kathmandu Valley WHS is one-of-a-kind cultural heritage - it has seven monument zones, and each monument zone has a large number of listed monuments. The typologies of these monuments vary functionally from temples and palaces to public urban resthouses and pavilions, and their building materials and structures are also as diverse. It also brings together built heritage in the middle of a living town along with sensitive and active religious sites and theaccompanying rural environment of those sites. The complex nature and extent of the identified and outlined heritage property in itself and the requirements of the World Heritage Convention had come together as a huge challenge for the field of conservation itself. For the Department of Archaeology (DoA), as a state party responsible for the management of authenticity of the inscribed heritage, it was a big call, especially as the DoA had been slow in building up to the large scale of national conservation needs. The practical learning process to understand the problem and issues in heritage conservation had already started with the UNESCO-sponsored project for the Hanuman Dhoka in the Kathmandu Monuments Zone (1973-1978), which targeted the conservation of both the terraces and the tower pavilions of the palaces' main residential court, the Lhohn Chowk. The approaches and practices followed there were documented and published by UNESCO. At under the title -Building Conservation in. Nepal: A Handbook of Principles and Techniques about the same time, a fifteen-year-long Bhaktapur Development Project financed through grants from West Germany had also started and undertook several architectural restoration activities, including Pujarimath, a sprawling complex of priestly residences of significant historical, heritage, and crafts values. Another set of approaches and standards in restorative conservation was developed and applied here. Although not officially endorsed, the interventions and reconstructions undertaken with Hanuman Dhoka and BDP appears to have become a reference norm for DoA.

But with the inscription, all such approaches and interventions became subject to expectations of the WHS convention and the expert scrutiny of the WH Committee. Reversibility of interventions, limited use of cement and restrictions on reinforced concrete intrusions as strengthenings (Skopje, 1985) were building up as basic requirements – these had brought into question the acceptability of reinforced concrete strengthening measures applied in the major restoration projects in KV WHS monuments zones. And by 2003, just the impact of regular developmental activity on the architectural fabric of the envelop in unlisted buildings in the edges of its buffer zone and urban changes happening around in its buffer zone itself had been enough reason for the World Heritage Committee (WHC) to put KV WHS into the List of Heritage Sites in Danger (LSD). In 2010, it reverted to the regular WHS as DoA registered a new management plan as a remedy.

Between 2003 and 2010, Nepal undertook the restoration of the 55-windowed palace in Bhaktapur Monuments Zone – a listed WHS building that had been restored in the past in several interventions following the 1934 Earthquake. Undertaken jointly by DoA and the Municipality of Bhaktapur following decade-long public consultations involving national and expatriate specialists, it was fully planned and executed by local expertise and followed traditional materials, methods and processes . Like the Hanuman Dhoka project, it provides a clear comparative example of conservation action undertaken in the valley under expert preview. However, both the Hanumandhoka project and Restoration of 55-Windowed Palace were, like the Kathmandu Valley region and the hundreds of other buildings listed in the monuments zones of KV World Heritage were under threat of a huge earthquake expected to hit as they were already in the estimated one-hundred year repeat period of the great earthquake of 1934, which was massive one of Richter Mw = 8.4. Considerations of strengthening against earthquakes had been a requirement for developing the approach to any restoration/conservation project in the valley.The project Hanumandhoka had approached the conservation works of bricks and woodworks largely based on the methods and know-how of traditional craftsmen. It had used cement mortar rather freely and high-handedly, even approaching the strengthening of architectural structures by introducing concealed concrete ring beams into the traditional historical monument. In contrast, the 2003-2008 project for the conservation of the 55-Windowed Palace had started with actions to remove brickwork where cement had been introduced in the seventies and the restoration actions were based on the use of traditional knowhow and skills, materials and methods. As part of structural strengthening, timber uprights had been inserted concealed behind the outer board of the straightened main wall, which held both the defining elements of the building mural on its inner face and the 55 windows on the outer face.

The Gorkha Earthquake and Destruction of Heritage

When the major earthquake happened on April 25, 2015, its force was comparatively less than expected with a moment magnitude of Mw = 7.8 and numerous strong aftershocks including one with Mw = 7.3 on May 12. It caused extensive destruction, damage, and suffering in central mountain regions, e.g. (i) 8786 deaths and 22491 injuries, (ii) 469000 houses destroyed, and (iii) massive damage to heritage monuments with 133 collapsed, 233 heavily damaged and 554 partially damaged . The government’s Post Disaster Need Assessment (PDNA) document states that the earthquake affected about 2900 structures with cultural and religious heritage value. PDNA assessed that the total estimated damages in terms of tangible cultural heritage alone were 16.91 billion NRs (US$ 169 million).

Of the completely damaged 133 structures, 25 were in Kathmandu, 13 in Lalitpur and 78 in Bhaktapur. In Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Site (KVWHS) alone, 33 monuments had collapsed, while 107 suffered heavy damage and 40 sustained minor damage. Significant sections of the three palace squares monuments zones and the unique architecture and ensemble of the urban centers had been knocked down to the ground. The top floors of the Basantpur Tower of Hanumandhoka Palace had collapsed while some other elements of the 1978 Lhohn Chowk conservation works were damaged. The top floor of the Keshav Narayan Chowk court of the Patan Palace had suffered major cracks. While the recently restored 55-window palace of Bhaktapur Darbar was unaffected, its Laldarbar wing was severely affected. Of the 17 monuments that collapsed in the Palace Monuments Zones of the Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Site (KVWHS), 10 were built in the tiered style, the typical traditional multi-roofed buildings famed for their art and craft in wood and brick.

The massive heritage damage, the fallen monuments and the streets and squares they had rendered inaccessible sent shock waves and numbness in the living Kathmandu valley cultural community. And, as the numbness wore off, the first concern the community voiced was about how to go about the fast-approaching festive season and celebrate the festivals, when the Newar community of the valley had been regularly living out its traditional cultural heritage in gay abandon in these streets and squares. The heritage disaster in KV WHS in particular had also precipitated a great national cultural identity distress while debilitating the cultural tourism economy of the nation. An annual loss amounting to US$ 6 m was estimated to result from a decline in ticket sales to KV WHS monuments and sites alone.

The Government of Nepal went on overdrive to deal with so-called ‘negative’ image of large-scale damage to heritage resulting from the world media coverage of the horrific aspects of the earthquake and it instructed local authorities to ‘open’ the heritage sites, particularly the monuments zone of the Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Site, as soon as possible. A second surge of debris removal using heavy PCVs began as a result again debilitating the already very feeble activities of rescue, recovery, inventory and secure storage of architectural, artistic and craft artifacts and pieces. Ironically, although listed as the last in priority in the social sector, heritage and its rescue, recovery, stabilization, rehabilitation and reconstruction had gained national priority not so much as a cultural or identity issue but more as a matter of national economy as so much of Nepal’s tourism depended on its cultural heritage, particularly of the Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu Municipality, which managed tourism in the urban spaces of the Hanumandhoka Monuments Zone, declared it open on 27 June, although some spaces and monuments were kept barred with signage and security tapes.

For the conservationists, the tragedy of heritage that had started with the earthquake quickly worsened with the ‘rough-shod search of a living and injured under the rubble’, ‘demolition of unsafe structures’ and ‘debris removal’, both of the latter undertaken as part of public safety action in heritage areas. But from the perspective of the human tragedy of the community trying to get back to living, the urgent need to accomplish such actions in the living city space context also deserves sympathetic understanding. These actions had community approval even as awareness had sunk in that the use of heavy machinery in such a context could lead to further loss and salvage of crafted and artistic elements impractical. Also, as weeks wore on, the woes of the heritage structures that were partially damaged by the earthquake but deemed safe enough to await stabilization and restoration worsened as the monsoon rains started – most of them deteriorating very quickly for lack of temporary rain cover of even plastics or tarpaulin.

PDNA calculated the cost of recovery of heritage at the estimated value of damages plus 20 percent to build back better (BBB) through the use of high-quality building materials and structural improvements for seismic strengthening (DRR). Storage of traditional building materials such as timber and bricks was expected. It would also only further exacerbate the dwindling availability of traditional skilled workers and craftspersons such as bricklayers, carpenters and wood carvers. The technical capacity of DoA to handle the required high volume of reconstruction of heritage was far too short.

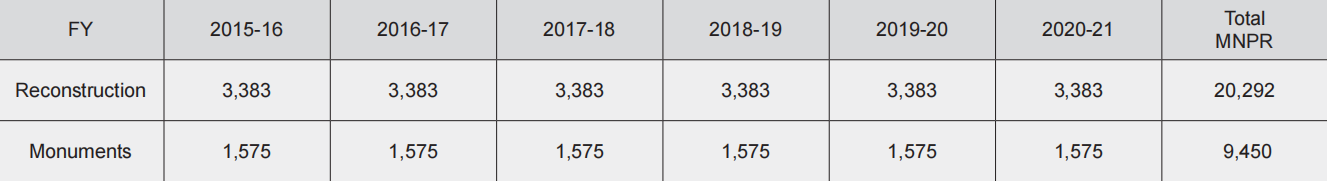

PDNA’s estimated reconstruction funding plan was huge and ambitious. It envisaged the restoration and reconstruction of all collapsed as well as damaged monuments and none were to be left out. The budgetary outlay is sought as follows: (Table 1)

International and National Scrutiny of Post-Disaster Reconstruction

Even as the valley heritage was no stranger to periodic large earthquake damage and successful large reconstructions carrying its authenticity, integrity and values forward led and carried out largely by the logic, skill, know-how, and capacity of local construction traditions and manpower had been undertaken before, the scale and nature of the 2015 damage and collapse did set the modern building engineering specialists on questioning the right or wrong of the structural system of the built heritage itself. Quick reactions in general tended to fault the structure as well as the materials and methods of construction of these buildings. Even the government’s Post Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) had hastily professed “to build back better through the use of high-quality building materials and structural improvements for structural strengthening”. In particular, the traditional building materials like mud, brick and timber and the associated technology and structural craft therein like joinery and mortar, were singled out to be the key factors of weakness and non-performance. So much so that official policy documents even recommended making it mandatory to rethink its conservation laws and remove restrictions on the use of modern materials and methods of construction while rebuilding heritage (GON, 2015)!”

Nepal’s response to rescue, recovery and stabilization of its damaged heritage was assessed to be so disastrous, ineffective and oblivious to accepted norms and practices that as early as July 2015, the 39th meeting of UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee (WHC) debated whether to put KVWHS in the List of Sites in Danger (LSD) considering the threat of ‘ascertained and potential loss of integrity and authenticity’ (WHC, 2015). While the threat of ascertained loss of integrity and authenticity of heritage, here, referred to the loss as evidenced in the nature and extent of earthquake damage, the added threat of loss was felt resulting from the nature of rescue, recovery, protection and stabilization activities and their lack of appropriateness and effectiveness in saving the integrity and authenticity, and thence the OUV of the heritage property, and the likely damage future processes and actions of restoration and reconstruction, if continued in the same vein without reasonable care and follow up within the international guidelines and practices, would do. Following the plea of the state party of Nepal, the WHC decided to send a reactive mission to review the post-earthquake processes on site and progress made and to reconsider the state of the heritage property in its next meeting. It is notable that the SP DoA of Nepal did not want KV WHS to be placed in the List of Heritage Sites in Danger (LSD) and provided the State of Heritage Property annually including the processes followed and progress made in restoration and reconstruction of the earthquake damaged property and warded off WHC presser every year during its annual meetings. Reactive missions continued to voice their disagreements on the process followed, e.g. ‘practice of procurement of heritage restoration and reconstruction through lowest bid tenders, disregard of accepted guidelines, norms and practices, and continuing damage to authenticity and integrity of the tangibles and erosion of their intangible content’. In its 2016 decision, WHC had noted that the traditional process of cyclical renewal of traditional materials and elements using traditional skilled manpower held the potential for saving authenticity and integrity. It had also urged the SP DoA to engage the community and its traditional institution of Guthi in the conservation process. This sequence of responding to comments and observation of Reactive Missions through the annually updated State of Heritage Property report continued year after year. In its 2019 decision, WHC reiterated its view to consider, in the absence of significant progress and continuing damage to the site’s OUV, the inscription of the property on the list of World Heritage in Danger. In its 2023 decision, it notes the monitoring mission’s observation that conservation actions continued to have adverse effects on the authenticity of the property and that they were also being focused on monuments at the expense of other attributes and called for ‘full implementation’ of the recommendations of the Monitoring Missions. It also established the International Scientific Committee for Kathmandu Valley (ISC-KV) to monitor progress in the future, presumably dropping the standing WHC agenda considering putting KV WHS in the LWHD at the behest and support of the Chinese delegation.

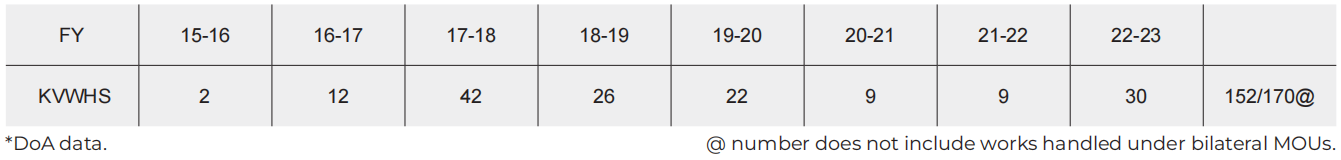

By this time, Nepal had accomplished the restoration and reconstruction of almost all the monuments listed in KV WHS as well as others affected by the earthquake. This can be seen in the following summary table of DoA-led restorations and reconstruction projects in Kathmandu Valley: (Table 2)

Within Nepal too, the concern for proper reconstruction of heritage was expressed loud and clear both by the body of conservation professionals and the community at large, particularly the body politic of the Newars of Kathmandu valley. Almost immediately, social and political influence makers had started grouping and creating large forums where conservation professionals and other experts were asked to present damage assessments, technical issues like costs and funding, materials and methods to be followed to meet the demands of the World Heritage Conventions and also to justly and sensitively reconstruct the national heritage and cultural identity to the best of local abilities and knowhow.

Happening amid continuing aftershocks, these meetings acted not only as public awareness campaigns against haphazard handling of restoration and reconstructions but also helped evolve the approaches, norms and standards to be followed by the government agencies involved in restorations. We find the society gearing up to meet, discuss and elaborate on the community watchdog functions quite early on. One such early large meeting of architects, archaeologists, historians and other concerned individuals was actually in session in Bhaktapur when the secondmajor jolt of the earthquake happened on May 12, driving the participants out in the open to face further damages to the already hard-hit monuments. Call to the government ‘to the use of traditional materials, traditional technology, and traditional craftsmen’ in reconstruction projects was growing all around in such forums (Tiwari S. , 2019a). Later, when a Kathmandu Municipality-led reconstruction project for Ranipokhari started placing reinforcements for cement concrete columns, Newar youths took to the streets and forced a stop to such ‘unacceptable modern intrusions and additions.’ This incident highlights the level of awareness and commitment among the local community to get the heritage reconstruction done right. As early as February 2016, this author had proposed the principle of ‘community-based AVI- navikaran’ for the restoration and reconstruction of KVWHS be adopted to protect and preserve the A-authenticity, V-value and I-integrity of heritage to the extent possible (Tiwari S. R., 2016). It sought to keep reconstructions tied within the possibilities of earthquake resilience offered by the renewed use (navikaran) of traditional materials, methods, processes, and craftsmen by proposing that performance of each monument be carefullyanalyzed in three steps while all the time keeping the traditional materials, methods, skills and knowledge in highest regards – (a) expound, glorify and promote the traditions, (b) past interventions – both pre-concrete and post-concrete, and (c) state of maintenance and decay. Since KV heritage architecture was a result of the traditional builders’ millennia-long experience of dealing with deterioration and destruction arising out of continuous action of big earthquakes and other deteriorating agents of the valley environment, the best approach to regaining AVI would lie in reconstruction using as much of traditional structural systems, materials, methods, processes, skills and knowledge as possible, which would automatically protect and preserve authenticity, value and integrity to the extent needed. Given the criteria of incorporation of KV WHS and the state and nature of authenticity, values and integrity of the property as it was in 1979 CE, it would be right for the reconstruction of the KV WHS heritage to aim for a gain of AVI as reinterpreted in the context of Nepal’s traditions of ‘cyclic renewals’ (Tiwari S. R., 2017). The evaluative position taken for the cases of reconstruction and their AVI, both as nominated and as reconstructed, and we should deliberately differentiate the two, is specifically responsive to the inherent cyclical renewal process and centuries-old tradition of conservation practiced in the heritage architecture of Kathmandu Valley (Tiwari S. R., 2009). It sets the standards for the post-2015 reconstruction, borrowing from traditional practices after similar cataclysmic ‘environmental events’ in the history of the valley itself. Reconstruction of severely damaged and collapsed monuments of KVWHS is thus taken as a case of ‘continuing traditional cultures’ (Jokilehto & King, 1998) promising to best follow the ‘living tradition’ in as many of aspects such as forms, methods of construction and craftsmanship, materials, and socio-religious rituals as possible.

Within eight months of the quake, DoA had also come up with ‘Conservation Guidelines’ following a series of consultations with conservation professionals and other stakeholders. Although it recognizes the continuation of traditional technology along with the retention of traditional structural systems as requirements, the wording of guidelines could easily be interpreted to reject the use of traditional materials and systems in the interest of earthquakeresistant rebuilding and or the national slogan of building back better. The allowance for new materials and structure was particularly left open by the guidelines given for reconstruction of collapsed (31g, 31h)and heavily damaged structures (32d) and these were, in quite a few cases handled by DoA itself, misused to reject traditional materials like mud mortar or even replace the foundations of the heritage structure (Tiwari S. R., 2073BS). The guidelines required the use of traditional skilled workers as an authenticity measure. It also requires reversibility whenever non-traditional material and system intrusions are made.

Evaluation of AVI response of Restorations and Reconstructions

Restoration and reconstruction of the built heritage started almost immediately with the government committing to fund it on the scale as needed. DoA expanded its technical staff by adding over 20 architects and engineers to prepare detailed drawings and documentation, estimation of quantities and costs of reconstruction for individual monuments. It had set up and tasked a special unit, the Earthquake Recovery Coordination Committee (ERCO), to coordinate salvage, stabilization and protection of sites and monuments in the KV in general and the WHS Monuments Zone in particular. Actual on-site reconstruction had also been started by November and it was reported that DoA had signed contracts for initiating works in 30 sites. International assistance in terms of money and expertise was received in several cases including from the United States (restoration of Panchamukhi Hanuman temple and Gaddi Baithak at KMZ), Japan (Agamchhe, Siva temple at KMZ and Degutale at PMZ), China (Basantapur Tower and Lhohn Chowk terraces in KMZ, Nuwakot Durbar), and Getty foundation (Kileswor temple at CMZ). By April 2016, the restoration of the main temple of Changunarayan had been completed by DoA using traditional methods and craftsmen and direct government funding. (Table 3)

Although the use of the local tradition of ‘cyclical renewal carried out by craftspeople using traditional processes and materials’ had been recommended for sustaining authenticity and values, WHC monitoring missions apparently did not see that happening in DoA executed works. It is difficult to understand how or why DoA would continue to work and complete over 90% of its targeted reconstructions and yet fail to extract good marks from the reactive missions. However, with whatever level of AVI recovery and gain had been achieved, Nepal did succeed in its aim to keep KV WHS out of LSD.

This article reviews the case of the following seven monuments to examine each in detail for the nature of damage and approaches, processes, methods and materials used in its restoration and reconstruction and to analyze those actions in terms of their effectiveness in preserving the authenticity, values and integrity of the heritage monument. It will also identify actions that lead to a severe compromise in authenticity or loss of values of the monument. Cases have been chosen to reflect a variety in restorations made, e.g. monuments of different historical and stylistic traditions and types and or managed by different implementing agencies as well as the use of different procurement methods.

1. Gaddi Baithak, KMZ, In-Situ Restoration (Miyamoto International Consultant)

2. Kasthamandap, KMZ, Reconstruction (Kasthamandap Reconstruction Committee)

3. Charnarayan temple, PMZ, Reconstruction (Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust)

4. Nritya Batsala temple, BMZ, Reconstruction (Bhaktapur Municipality)

5. Ratomatsendranath Temple, Bungamati, Reconstruction (DoA)

6. Manimandap, PMZ, Reconstruction (KVPT)

7. Bouddhanath Stupa, Bouddha MZ (Bouddhanath Development and Conservation Committee)

1. Gaddi Baithak, KMZ, In-Situ Restoration and seismic strengthening (Miyamoto. Relief)

This monument, built in 1908 CE in Post-Victorian British Classical style and forming a part of the Palace complex of Kathmandu Darbar Square Monuments Zone, was heavily damaged in the earthquake and had been stabilized using some temporary supports in the emergency and rescue phase. Its restoration was funded internationally (United States of America) and managed and supervised by deputed international consultants. Detailed structural and constructional assessment and restoration details aimed at repairing and structurally upgrading the monument were prepared and implemented by engineers specializing in earthquake performance and architects specializing in heritage building preservation and reconstruction. The involvement of local professionals was significant in detailing and supervision. Work items involving skilled masonry works, carpentry and other traditional construction techniques were supplied under contract by a group with previous experience on restoration works in the palace. Material supply was arranged through prudent shopping. It followed an itemized in-situ restoration process and did not go through the national public procurement regulations. Involvement of the community as well as DoA and other state agencies, was minimal with general participation in administrative meetings. Works were accessible for observation by local conservation professionals.

The physical fabric of the structure remains essentially the same as before the earthquake and the strengthening elements added were unobtrusive and largely reversible (timber wall ties, timber bracing of parapets and timber plank diaphragm ceiling). Steel ties have been used in the east and west corner blocks. Walls were repaired using matching mortar and columns have been strengthened with the introduction of reinforcing bars. It has successfully saved the authenticity and historic, technological and decorative values of the building while enhancing its earthquake performance to meet its adaptive use as a public museum space. Documentation and description of interventions, restoration and strengthening works have been published as a booklet, ‘Restoration and Seismic Strengthening of Gaddi Baithak’, 2018, by the US Embassy Kathmandu.

2. Kasthamandap, KMZ, Reconstruction (Kasthamandap Reconstruction Committee)

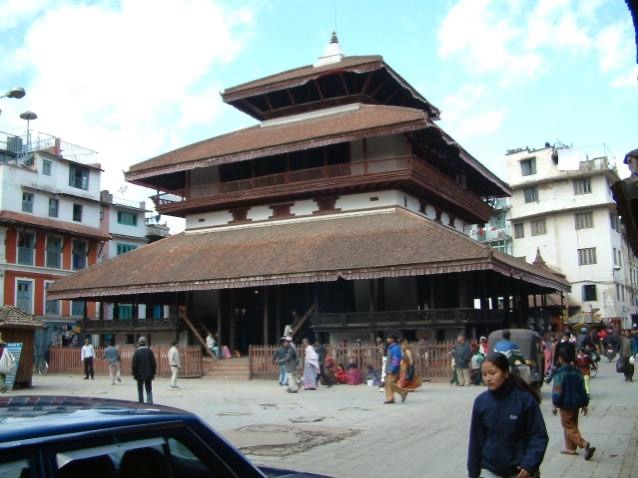

Kashthamandap, a three-tiered mandapa temple turned sattal structure in the famous brick and wood architectural tradition of Kathmandu valley, built in the seventh century CE at the central crossroad of Kathmandu town, faced a total collapse in the earthquake. This rather plainly embellished multi-roofed wooden structure had a great socio-cultural value, having given its name to the city and the valley had stood as the oldest known monument in Kathmandu Monuments Zone of KV WHS. The monument, which had survived the huge earthquakes of 1934 and 1833 unscathed, showed in the post-earthquake Archaeology performed on its site, foundations, salvaged timber elements and fragments and carpenter’s identification marks found on the brackets (metha) of the main timber posts, indicates at least two more major renovation events undertaken before 18th century, including ones needing replacement of its huge central posts and capital systems. These have been dated to 9th, 11th and 15th centuries through C-14 and OSL tests (Coningham, et al., 2017)).

The historic value of the monument has been enhanced through the same studies which confirmed its 7th-century construction and use of a 5th-century timber capital (metha). The monument had also faced heavy-handed use of types of equipment during the emergency rescue and debris removal operations further damaging the historic material values of the site and the ruins. The stocktaking inventory of salvaged woodworks was completed only in October 2016, one and a half years after the earthquake!

Post-earthquake Archaeology assessment had concluded that ‘the components of the foundation and the method of their construction apply core principles of earthquake resistant strategies and contribute to the resilience of the superstructure of Kasthamandap’ adding that ‘the traditional method of foundation design highlights a cultural knowledge of earthquake damage mitigation’ (Kelly, Callum, & Simpson, 2019). Further research done by the Kasthamandap Reconstruction Committee on the mud mortar used in the brick foundation walls has revealed that the mix ratio was uniform throughout and well within the present-day recommendation of clay 18-22%, silt 40-45%, and sand 30-40%.

Earthquake performance assessment on the extant structurerevealed no serious flaws in the overall scheme and design and the foundations have remained intact despite several big earthquake actions on it. Only a general strengthening of the corner brick piers by introducing timber uprights and horizontals was recommended as an addition. The collapse of the monument has been attributed to poor and incompatible restorations in 1968 (when its timber plinth ties and floor structure were replaced by brick paving and one of the central posts was left hanging over a support stone), lack of regular maintenance of roof and its timber understructure and joints.

The reconstruction of Kashthamandap became an issue almost as soon as it collapsed, and all of the governments of Nepal, Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC), and local communities pledged to fund and rebuild it. The initial restoration proposal prepared for DoA by a local engineering firm, which had recommended, among other interventions, large-scale nonreversible intervention on the foundations, was rejected (January and March 2016), and it further aggravated disagreements. As an implementing agency, KMC was also caught in its bureaucratic and procurement regulations as it sought to carry out the reconstruction as a regular construction tender activity. In the meanwhile, the community and heritage organizations were campaigning against heritage reconstruction through the use of the lowest bidder contractor obtained through a tender process, and several of DOA’s and KMC’s heritage reconstruction projects were stopped through community action. A community-based organization called Rebuild Kasthamandap was then signed in by the National Reconstruction Authority (NRA), DOA, and KMC for the reconstruction of Kashthamandap on May 12, 2017. But before it could start working, the newly installed Mayor of KMC, elected under the new constitution, pronounced that KMC would take up the reconstruction by itself. But that, too, failed to move any further than putting a tin shade protective over the excavated foundations under political crossfire and the stranglehold of its own bureaucratic and procurement regulations. Only another year later, the Kasthamandap Reconstruction Committee was authorized to manage an authentic reconstruction with maximized use of traditional architecture, construction materials, methods and processes, skills, and knowledge. It followed the procurement process of ‘force-account’ using select traditional skilled carpenters and bricklayers. The first salvaged bricks were put back in the foundation on November 8, 2018. Survey and laboratory tests of the ancient bricks and mud mortar used in foundations were made, and the size, shape, and strength specifications for new matching bricks to be manufactured and the mix ratio of sand, silt, and clay for new mortar were fixed. One of the main central posts dated to the 11th century CE and four other salvaged ones were accepted for reuse. The very idea and realization of putting these posts back into the reconstructed structure along with the fifth-century metha atop the north-west post (Fig. 2) and the 11th-century post making the south-east member, both of the central sanctum set, have not only helped regain material authenticity substantially for the monument but also added much to the heritage storytelling vocabulary of the rebuilt Kasthaman dap.

The reconstruction proposals and drawings were prepared under the principle of truthful, authentic rebuilding of the original with minimum intervention and changes and were based on archaeological findings and site measurements along with available documentation such as drawings and photographs. Apart from the introduction of timber uprights and horizontals made into the corner brick piers for structural reasons, Kasthamandap was reconstructed exactly as per the original architectural and constructional design and details following the traditional construction process and using traditional tools. From the use of traditional bamboo scaffolds with jute rope ties, manual hoisting and placing of all kinds of building materials such as bricks, tiles, mud and timber posts, beams, rafters, etc., to the mobilization of community labor for salient and symbolic works, the reconstruction had followed the traditional building reconstruction process itself to regain authenticity of a symbolic level too.

3. Charnarayan temple, PMZ, Reconstruction (Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust)

This two-tiered temple of Charnarayan, built in 1565 CE by Purandersimha, thirty years before Patan was restored to Malla rule from the hands of dynastic local mahapatra, is the oldest and most valued iconic representation of traditional Newar architecture and craftsmanship. Built in the Sivalaya devalaya (Pashupati) format, it houses a four-faced image of Narayana and forms a key monument in the Patan Monuments Zone of KV WHS. It totally collapsed under the action of the earthquake with only its plinth structure surviving. Its restoration was funded as well as executed by the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust, an international charity with twenty-five years of valued and recognized conservation experience. The rescue, salvage and storage operations in PMZ were also led by KVPT and there has been all-round appreciation and praise for professionalism in the works.

KVPT worked under its own procurement rules and the use of traditional skilled craftsmen (particularly in wood working and carving) in restoration activities has been standard.

With almost all the wooden and stone elements and fragments salvaged from the rubble and a prior plan, elevation and section documentation available from earlier studies and publications, KVPT’s reconstruction of the Charnarayan temple is almost an exact reerection of its original form and shape. The reinstatement of almost all original wood and stone pieces into the rebuilt structure has been able to save its authenticity, integrity, and values to its utmost. Archaeological opening of foundations was made and the space between the two foundations was rebuilt packed solid with brick in mud mortar, replacing the traditional brick infill laid on dry and sandy mortar. Although several interventions were proposed for discussion with DoA, in actual reconstruction no new structural strengthening input was deemed necessary once the tripartite door portals and their inner structural frames were repaired and traditional joints reinstated. A quick resetting of the sanctum for worship purposes and the involvement of the priests and the local community in bringing back the worship ritual function is believed to have restored intangible values early enough to enable a smooth reconstruction process.

4. Nritya Batsala temple, BMZ, Reconstruction (Bhaktapur Municipality)

This monument, built in 1678 CE in stone in the Granthakuta style by King Jitamitra Malla, houses the goddess Batsala in the form of a purna kalasa with a carved image of Nrityanath under and Sriyantra carved on top and forms a part of the Palace complex of Bhaktapur Darbar Square Monuments Zone. It had been damaged in several earthquakes in the past and rebuilt fully or partially in 1700 CE, 1835 CE and 1934 CE. It was damaged in this earthquake with only the three-stepped plinth surviving. Its restoration was funded locally by the Bhaktapur Municipality and was achieved under its public procurement regulations using a Consumer Committee of local social leaders. The committee was chaired by Ramhari Gora and worked under the reconstruction policy of retaining original form and style, using original methods and techniques and local traditional skilled crafts backed with as much study, research and analysis as possible.

Detailed documentation of the measures, proportion and décor of the temple was available from previous repair and renovation events. Excellent salvage and rescue operations had made it possible to reuse a large number of carved stone pieces during restoration. An archaeological excavation was jointly made by Durham University, Bhaktapur Municipality and the Department of Archaeology to investigate the plinth and foundation edges.

Architectural documentation and detailed earthquake performance and structural strengthening assessments were undertaken by technical committees formed of select faculty of Khwopa Engineering College and Khwopa College of Engineering.

Architects experienced in reconstruction from the Heritage Unit of the municipality provided technical supervision. All stone and woodwork were done manually by local traditional craftsmen.

Kanchha Ranjitkar, 77, with lifelong experience of traditional stoneworking, was the lead stone cutter and carver. Works were accessible for observation by other conservation professionals.

Except for the introduction of timber frames and bracings for strengthening of its earthquake performance and the replacement of the broken brick cover on the inside of walls by stonework, no material change has been made to the physical fabric and overall dimensional aspects of the temple. As per DoA Guidelines, the original mud mortar was replaced by lime mortar.

It has successfully saved the authenticity and historic, manual skill, technological and decorative values of the building while enhancing its earthquake performance by introducing a concealed system of wood frame and bracing. Documentation and description of interventions, restoration and strengthening works as well as the participatory process, have been published as a booklet, ‘Nritya Batsala Mandir Punahnirman’, 2078, by the Bhaktapur Municipality.

5. Ratomatsendranath Temple, Bungamati, Reconstruction (DoA)

This granthakuta ‘Shikhara’ temple of Rato Matsendranath at Bungamati believed to have been consecrated in the 12th century CE had totally collapsed in the 2015 earthquake while its grand annual chariot festival was in progress in Patan. On-site postearthquake archaeology at the site, however, revealed foundations dated to the 16th – 17th century CE. The fallen structure was one rebuilt after what had collapsed also in the great earthquake of 1934.

This temple of Rato Matsendranath (Karunamaya) is not listed within KVWHS but its socio-cultural value, particularly arising out of intangibles associated with the cult of Matsendranath and its annual chariot festival, the religious value accruing out of the high religious and faith-based veneration that Matsendranath commands from both of its Hindu and Buddhist followers and its symbolic values built on its mythical linkage with the farmers, tantrics and kings, and nagas and rains have made it a living heritage par excellence of Kathmandu Valley.

The rescue, recovery and debris management immediately after the earthquake were largely coordinated by temple priests withhelp from local residents. With funds made available by the Government of Sri Lanka, the reconstruction of the temple was managed directly by DoA. Consultants were used to make necessary documentation and drawings based on site measurements, previously available drawings and photographs. The works have been undertaken by a contractor assigned to the project through a bidding process as per government procurement guidelines.

While the archaeologist had recommended that the temple foundations were intact and should be preserved, DOA decided to remove the extant foundations and built a new one using new bricks in lime-surkhi mortar (bajra) and in effect destroyed the original historic foundations and plinth. As part of structural strengthening, a multiple-box frame of timber was introduced from the ground level up to support the Shikhara structure above.

It appeared over-designed and excessive. No structural analysis document has been made public by DOA. The monument was built back to the previous fabric and measured ground up by the contractor amid local opposition and other disputes. The works had taken over nine years to complete!

6. Manimandap, PMZ, Reconstruction (KVPT)

The twin wooden pavilion in open sixteen-pillared ‘sohrakhutte’ mandapas format flanks the main stepped approach to the pit conduit of Manihiti in the Patan Durbar Monuments zone (PMZ) of KV WHS. Historians generally date the northern pavilion as an eighteenth-century reconstruction based on an inscribed record of an annual festive event held there (1701 CE). But the nine-pit plinth and foundation structure of the southern pavilion portend to be the remains of a Lichchhavi period water distribution utility for Manihiti as its supply branched along Mwomadugalli from the main irrigation canal that ran through Mahapal-Konti street. Traces of this water structure were still evident till the 1975 renovation, when its timber ties and floor structure were removed and replaced with stone paving. Inscriptions at Manihiti going back to ancient times also remember the ancientness of the water system.

Both of Manimandap structures had totally collapsed and fallen down into the terraces of Manihiti conduit pit in this earthquake, while they had both survived the 1934 earthquake on the strength of their traditional technology and structural configuration. The restoration was funded by a group of international and national donors coming together to support the initiative taken by Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT). The restoration was procured by KVPT under its own charter and used woodwork and wood carving expertise provided by Silpakars from the traditional skill house of Bhaktapur and led by master carver Indrakaji Shilpakar.

On-site recovery, salvage and storage of wooden architectural elements were done by the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT). The structural disconnect introduced by the removal of timber ties and floor structure in 1975 restoration and consequent deterioration of timber posts by damp action as well as the wrongly detailed application of bitumen sheets for roof waterproofing contributed to the collapse of the structure, which had survived the 1934 earthquake on the strength of its traditional technology and structural configuration. Drawing and documentation for restoration were prepared from measurements of the site and salvaged timber elements and fragments supplemented by old photographs.

In April 2016, KVPT sought DOA permission to change the traditional foundations with the introduction of concrete pads, steel ribs for the four central posts and steel grillage foundation, and reinforced concrete floor slab in a project proposal for the reconstruction of this Mandap (KVPT, September 2016, pp. 84-98).

While this was not granted, KVPT went ahead with the excavations of the floor and foundations and cleared ‘trash from the site’, leading to the total erasure of archeological signatures of its past.

The usual nine-pit mandala foundation of the mandapa, which reflected the pavilion plan configured with sixteen pillars, twelve on the periphery and four placed around the central square (Tiwari S. R., 2009), was replaced by a new brick in lime-surkhi mortar foundation walls configured to allow the introduction of steel stiffened columns on the new built-in reinforced concrete pad.

This offensive handling of the heritage foundations from an organization like KVPT done in total disregard of the guidelines and international norms deserves condemnation. The loss to Newar heritage caused by this is irreparable and irreversible.

Except for these intrusive missteps and their repeated use in the north pavilion, the repair and restoration of the rest of the architecture and fabric of the pavilions above the plinth, including posts and other woodworks, have been achieved with excellence.

The documentation of the restoration of woodwork has been presented in detail in KVPT publications (KVPT, September 2016).

7. Bouddhanath Stupa, Bouddha MZ (Bouddhanath Development and Conservation Committee)

The Bouddha Mahastupa is a Buddhist religious structure built in the Lichchhavi period as part of Sivadeva Monastery, which is held holy by Buddhists all over the world and Tibetans in particular.

Believed to have been built with the astudhatu of Kashyapa Buddha, it is recognized as a physical marker of the mythological and historical development of Buddhist religious practices. Its ancientness, historical, religious and artistic values are highlighted by its listing as a monument zone of KV WHS. The present structure is a 15th-century CE reconstruction. Its last major repair was done in 1968, when a fire caused by a lightning strike had damaged its pinnacle and a number of top steps of the upper structure. The upper structure of trayodashabhuvan was damaged in the earthquake and the resulting dislodging and displacing of the gold-plated covers were visible. The restoration was managed by the Bouddanath Area Development Committee (BADC), a site management committee organized and working under the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation there. Within days of the second quake, a ritual worship (kshyama puja) seeking an excuse to allow for going up for inspection, dismantling and reconstruction was offered. A damage assessment team led by a DOA engineer decided that the damage in the brickwork of trayodasabhuvan as well as its cubic base (laid in mud mortar) was very extensive. It was dismantled to the bottom of hermika and the top of the hemisphere. The reconstruction fund of about $2 million was met through donations of cash, gold and building materials made by local and Chinese religious and social institutions, religious leaders and individual donors, and the local community (Karki & Shrestha, 2016).

The dismantling of the upper structure of gajur, chhatravali, and padma and the outer gold-plated cover and its timber frames on trayodasabhuvan and hermika, demolition of the brickwork underneath, and collection, identification, inventorying and storage of retrieved items such as religious images, offerings and other treasures housed in boxes inside gajur and padma or encased in the brickwork of trayodasabhuvan and hermika were done under expert supervision so as to enable their systematic restitution in the reconstructed structure.

A concrete pad (2 feet thick and 28’-8” square) was cast to ‘make a strong base for the construction of the hermika cube and the trayadasabhuvan structure’, and a short 16 feet ‘soksing’ was erected on an 8mm iron plate (3 feet square) centrally over it. A salwood timber-framed box structure was introduced to encase and strengthen the earthquake response of the hermika and trayodashabhuvan brick masonry. The cube of hermika was built back with brick in lime-surkhi mortar, discarding the original mortar of mud. Likewise, the trayodasabhuvan was constructed like mass brickwork in lime mortar with timber box frames. A lime-surkhi plaster was applied over the whole of the masonry work. In addition, the whole of the upper structure was then encased in a copper plate cover before the old gold-plated cover (with new gold molamba) was put back. The chatravali structure was assembled back to the top with the support frame of the parasol cover done in metal.

The works were completed in eighteen months after the quake, making it the first of the world heritage monuments to be reconstructed completely.

The finished outer look of the reconstructed Bouddha Stupa is indeed resplendent and magnificent and reflects the support and goodwill of the religious community, the faithful and the craftsmen alike. But whether so much of religious symbolism, symbolic andheritage values was at all necessary to be sacrificed continues to challenge the conscience of conservation. Neither the damage assessment nor the reconstruction design has asked the question as to what led to the damage of the top four stages of the trayodasabhuvan in the 2015 earthquake. If this had been investigated, the reason for the kind of damage was more due tothe introduction of stiff concrete posts cast around the so-called yashin as part of the DOA carried out restoration of 1968, rather than the severity of the present earthquake.

A report of reconstruction is available titled ‘The Boudha Stupa Renovation 2016 – A Brief Study’.

Conclusion

So how effectively has the post-Gorkha earthquake reconstruction saved or regained the authenticity, integrity and values of KVWHS?

While the DOA guidelines seem to follow the international practices and norms in wording and seem to have worded most of the clauses within the right theoretical perspective, the actual reconstruction works, even those done under the direct stewardship of DOA, have failed to sincerely remain within bounds of authenticity, integrity and value protection and or gain.

Of course, among the 175 monument restoration projects undertaken in the seven Monuments Zones of KV WHS, there were varying levels of AVI recovery achieved: exceptional, mediocre and poor. Along with DoA, there were other agencies also working on restoration which followed different approaches to achieving appreciable gains on AVI standards set. While restorations undertaken by other agencies, such as Bhaktapur Municipality and KVPT, did not use the process of lowest bid tenders, DoA had continued its tender-based procurement approach, believing ‘community involvement and a robust contracting system yields productive results (Gautum, 2020). At the same time, KVPT was still calling for a ‘heritage friendly Procurement Act’ (Ranjitkar, 2020) and working in its own ways of procuring restoration works. Exceptional restoration and reconstruction work results can be observed in projects like the Gaddi Baithak and Kashthamandap.

At the poor end of the scale of AVI gain, one does find some works of DoA, like the reconstruction of the Rato Matsyendranath temple.Documentation can be assessed as satisfactory in most cases, although the restorations appear guided by accuracy in elevation and dimensional coordination. As even the collapsed structures had retained a clear trace of their plinth and plan dimensions and intact foundations, the replication accuracy in plan form has been highly satisfactory. However, given the nature of natural materialbased architecture, minor dimensional variations may not materially affect the proportions and measures in terms of authenticity. Although classical systems of proportioning and measurements are known, conservationists have used visual judgments to revert to ‘proportionate’ reconstruction (Ranjitkar, 2073BS). A sense of dimensional closeness to the original is also sought to be achieved through the reassembly and repositioning of key salvaged elements.

The loss of the heritage of structural principles and performance of local materials and technology in reconstruction, particularly in foundations and plinths, has been massive as seen in the case of Manimandap and Matsendranath temple. The reckless discardingof the traditional mortar (made of clay, silt and sand) and its replacement by lime-surkhi mortar have introduced such stiffness in place of resilience that only time can tell how costly this can prove to be – if nothing else, the characteristically salvageable nature of the heritage architecture is lost forever. The loss of the traditional foundation system (nine pits with designed infills) and the archaeological materials there has been immense. The reconstruction of Kashthamandap is the only case where mortars and foundation infills exactly replicating the original mud and mix were used. The use of lime-surkhi mortar can be said to have met compatibility requirements only in the cases of Gaddibaithak and Nritya Batsala.

Similarly, the introduction of irreversible materials and methods and the creation of strong monolithic masses through the use of industrial and stronger materials have destroyed the very principle of cyclical renewal through which KVWHS architecture had saved and preserved its authenticity over history. The case of Bouddha stupa even shows how the introduction of so-called earthquakeresistant measures has destroyed the symbolic, ritual and religious value of the monument itself – in this case, even the symbolic soul spine of a stupa, the earth-tree, has been done away with for engineering expediency. The technological intrusions made onto the Manimandapa foundations have been killing the heritage of traditional knowledge.

The exceptional quality of the restoration of Gaddibaithak may have been assisted by its post-Victorian British Classicism and materiality created by AVI and its greater compatibility with industrial materials and methods. The Kashthamandap case, despite the long-lasting delays and debates, comes off as the best and most successful case as it had sincerely followed AVInavikaran prioritizing all three traditions, e.g. traditional material, traditional process and traditional forms (Chen, 2012) to recreate its authenticity, integrity and value.

The post-2015 exercise of restoration and reconstruction appears to have firmly taken the motive behind the preservation of monuments more into its value as part of the national heritage from the earlier socio-cultural stance seen in the community’s motivation towards religious needs, historical reasoning and posterity in the past. Meanwhile, it seems that the authenticity of heritage has been reinterpreted and its values as a living heritage property requalified by the new level of community awareness and acceptance of the fact that the living heritage of KV is truly living Between Two Earthquakes, to borrow the title of Fielden’s famous work.

Fig. 1 Kasthamandap (pic. 2003) before the 2015 earthquake

Fig. 2 Kasthamandap (pic. 2024) after reconstruction

Fig 3 An overhead view of the reconstruction

Fig 4 Rato-Matsendranath of Bungamati – New foundation, sanctum platform and timber frames

Fig 5 Original foundations (left and center) removed and replacement made (right) (Tiwari S. R., 2073BS)

loading......

loading......