Author

Manindra SHRESTHA

Founding member of ICOMOS Nepal, Project Manager and Technical Team leader, Kasthamandap Reconstruction Committee

Email: manindrashrestha@yahoo.com

Abstract

Proven from post-earthquake archaeological studies to date back to the Licchavi era (78-880 CE), Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap has been an iconic monument after which the city of Kathmandu was named. Whilst the collapse of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap in the 2015 Gorkha earthquake was an unforeseen catastrophe, at the same time, it presented an unprecedented opportunity for revisiting the traditional heritage rebuilding process in the backdrop of the prevailing heritage conservation scenario, which is often criticized for its anomalous approaches. It also presented an opportunity for exploring Nevār heritage ideology, which has somehow been misinterpreted and often overlooked. The idea of livingness that is fundamental to Nevār heritage has largely been mistaken for associated human activities only. The reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was a novel exercise in its own right, taking a different approach with an intent towards improving the state of conservation practice in Nepal. It was a wider experimentation on approaches as well as on traditional materials and methods. Integrating facts, observation and commentary on various aspects, and also with narrative on underlying intangible implements, the paper intends to highlight the features that have been forgotten and lost ways in modern conservation practices. Given that, it intends to stress that in the arena of heritage, modern science and engineering should always be viewed to assist, rather than dictate or challenge traditional wisdom. Apart from the scientific aspects, the paper also intends to delve into the theoretical discourse on the approach towards reinstating heritage value, which may not comply with any scientific reasoning and are often case-specific. Additionally, a comparative study of the model adopted in two other projects will be presented to demonstrate why the model adopted in Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was unique, yet difficult to be adopted in other projects.

Keywords

Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap, living heritage, intangible, reconstruction, Nepal Mandal

Context

Way before being inscribed in the list of world heritage property, Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap has already stood for thousands of years as an iconic landmark after which the city of Kathmandu was named. Literally, ‘kāṣṭha’ stands for timber and ‘maṇḍap’ for pavilion; the word ‘Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap’ degenerated into ‘Kathmandu’ over time. As the name Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap suggests, it is a monument that has the prominence of timber in its make. Located at the nodal juncture of the Tibet-India trade route and within the premise of Hanumandhoka Durbar Square, it has witnessed several sociopolitical changes and recurring natural upheavals like earthquake throughout its history. For a considerable period in the past, it was apparently used by the wayfarers as temporary lodging on their journey, which is why it also came to be addressed as sattal (Nevārsataḥ; lit. rest-house), and more precisely as maru-sataḥ—maru is a shortened name of the locality coined after the temple of Maru Ganesh close by.

There were days when monuments like these were not noticeably appreciated for the historical and cultural values they had accrued over time. It was only after 70s that the upsurge of awareness on heritage and heritage conservation was faintly seen. Whereas in the past, the conservation efforts whatsoever, carried out to tackle the effects of ageing, weathering, mishandling and even possible dilapidation of the monument, went unnoticed or even unrecorded. At times, several conservation efforts might have been made in Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap, sometimes in the form of repair, renovation or even reconstruction.

Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was one of the monuments that was toppled to the ground in 2015 Gorkha earthquake. It was leveled up to its plinth level, which was initially covered with its debris. This led the general public to suspect whether Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap has no foundation. But the archaeological investigation, more in a nature of rescue archaeology, which was carried out by the Department of Archaeology (hereafter DoA) in coordination with the Durham University, revealed that not only the foundation was perfectly laid, it was also intact and not damaged in the earthquake. As a part of the same study, OSL dating of the central foundation structures revealed that they belong to the 7th century (circa). Similarly C14 dating of one of the wooden capitals atop the main post revealed that it belongs to the 5th century (circa). These results pushed the historicity of the structure to Licchavi era (78-880 CE), a date much earlier than what was previously believed to be the actual date of construction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap.

The reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap that followed shortly was approached as an exemplary exercise to showcase an applied conservation methodology that could open avenues for amendments in existing approach or possibly an adoption of similar approach in the future. It demonstrated the possibility of what could be satisfactorily achieved not only from technical standpoint but also in terms of value addition.

Fig. 1: Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap after reconstruction in 2021 (top) Photo: Author; Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap in 1952 A.D. (bottom) Photo: Johannes Bormmann

Fig. 2: Foundation of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap revealed in the post-earthquake archaeological investigation carried out by DoA/Durham University. Photo: Narayan Maharjan (Setopati)

Methodology

The paper is not entirely a scientific paper. Scientific approach is indispensable for analyzing various components within Nevār architecture but might not be an exhaustive and ultimate tool for grasping the wider spectrum the Nevār heritage has. The paper is prepared based on first-hand observation and commentary on the rebuilding process of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. The reference to secondary sources is made wherever deemed necessary. As the intangible aspects or aspects that can only be felt to exist are difficult to describe in scientific terms, a considerable mix of narrative and remarks is utilized to bring out the idea at par with the nature of Nevār heritage.

The initial rebuilding effort

In the aftermath of the 2015 Gorkha earthquake, extensive interactions with the wider circle of heritage professionals were carried out at the Department of Archaeology (DoA) to discuss the immediate approach to be taken towards rebuilding heritage. The central government had already formed a body, namely the National Reconstruction Authority (hereafter NRA) in order to ease the process of seeking international assistance and to oversee the reconstruction works of private and institutional buildings throughout the country. However, NRA was criticized later for the ad-hoc and ill prepared approach it has adopted in dealing with heritage structures. The reconstruction of national level monuments was initially entrusted to the NRA.

It was a time of grave horror for everyone, and even the so-called experts were seen with faltered faith on load-bearing system and in mud mortar, out of which most of the monuments were originally built. To add to the irony, the idea of ‘build back better’ was floated, which tacitly advocated the idea of using cement and concrete in the rebuilding process. The voices of the few prominent experts were not listened to, who stressed that the collapse of monuments did not occur because of the weakness on the part of original material and technology but rather because the traditional structures which need periodic maintenance were left in neglect to a point that they lost their structural and material integrity over time making them susceptible to damage or even collapse with even a slightest of the shock. In spite of wider opposition from the heritage professionals at large, the Department of Archaeology seemed adamant on executing projects with the hidden use of concrete and cement. For the moment, mud mortar was apparently ruled out from the dictionary of department to be replaced with lime mortar, which they presented as better alternative.

With the upsurge of rebuilding projects, the need to rebuild Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was also widely voiced from the general public. A prominent structural/earthquake engineer was appointed by the Department of Archaeology (DoA) as a consultant to carry out the structural analysis of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap and came up with a proposed design. Heritage professionals were flabbergasted with the initial design which not only proposed the use of concrete piles to strengthen the foundation but also introduced nontraditional measures like the use of steel, nuts and bolts. The designer had based his calculation on soil test report of nearby spots and selfdeclared that the foundation of this 1500 years old monument, which withstood several earlier earthquakes, was laid on the soil whose bearing capacity was not good enough. It had been geologically proven that the whole of Kathmandu Valley was a lake bottom. In spite of that, the past generations had laboriously devised ways to tackle any shortcomings the soil strata may have and had built structures that have withstood the test of time. Now the effort is being made to prove that previous technology and techniques were wrong and modern engineering solutions are the only better option. Time-tested inferences were discarded to make space for lab-tested ones. The proposal, which was presented among the experts and stakeholders, was received with severe criticism. The revised proposal, now with timber piling option, met with the same fate. A couple of interactions even with prominent heritage experts could not sway the consultants too far from the rigid engineering mind frame. In the end, the Department overruled in favor of a compromised option with the use of heavy timber plinth beams and the use of metal ties and bolts. The fact that the mix use of traditional and non-traditional measures has always proved to be detrimental during earthquakes was not properly realized by the decision makers. Even after extensive assessment of damaged monuments throughout Kathmandu Valley, the department seemed indifferent in learning the lesson. The drawings were approved and displayed for public review.

A lot of heritage professionals were disheartened by the approach the Department had taken. People who could read the drawings, voiced their disagreement but to no avail. In the meantime, the DoA started the process of lowest bidding system (tender system) for the reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. As per Public Procurement Act of Government of Nepal, the call for lowest bidders was the only option available with the DoA to carry out works of that scale and nature. As tendering was never accepted by the general public as good practice as far as heritage renovation/reconstruction is concerned, there was an utter objection, discontentment and disbelief that the work will be better executed in acceptable technical, material and financial terms. A spark of objection led to the swarm of activism and the DoA was hard stuck in starting the process of tendering. Besides, the DoA initiated the act of delegating the rebuilding work of individual monuments to the donor countries. Out of the fear that Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap will also be given away to some donor country, locals, scholars, researchers, professionals and youths all joined hands in protesting the idea and the fit of activism swelled to national and international frontiers.

In the meantime, independent volunteers had come together to form a working group namely Campaign to Rebuild Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap (hereafter CRK) that carried out a lot of research and documentation work for over a year, that also included an extensive study on the intangible aspects and elements associated with Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. With a four-party agreement between CRK, DoA, NRA and Kathmandu Metropolitan City (hereafter KMC) CRK was entrusted later with the work of rebuilding Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. However, after the immediate local election, the position of Mayor was reinstated in KMC, and with renewed institutional setup, KMC claimed over the work of rebuilding Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. Amidst a larger confusion, KMC finally agreed to a larger public-private partnership and a committee namely ‘Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap Reconstruction Committee’ (hereafter KRC) with over sixty members was formed under the steering committee of the Mayor. KMC also agreed to fund the implementation of the project.

KRC was formed as an independent body authorized to take decision in carrying out the reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. Twelve sub-committees including an executive committee were formed. And under the executive committee a group of experts and an in-house technical team were assigned. The group of experts included renowned experts in architecture and heritage, structural engineering, archaeology and other technical disciplines. The in-house technical team was assigned to execute the site works with frequent consultation with the group of experts. The matter related to finance was dealt by the executive committee. The whole approach was unprecedented and novel in its own right because no such exact model was practiced for any project ever before. The group of craftsmen was independently hired by the executive committee based on their prior experience. And with the working groups in place, the work was approached afresh as if from a clean slate—starting almost from scratch. The idea of using modern material and technology as proposed by DoA was ruled out from the very outset and the team was free to adopt traditionally accepted material and technology. It was the greatest of the victories ever won over the imposition of foreign ideas in terms of material and technology.

Adopting traditional material and technology — the first pillar of heritage rebuilding

When we talk about traditional material and technology in this context, it would mean the building art that is practiced by the Nevār artisans for thousands of years. If we go back, we may find a rich culture of building creed, the root of which can be traced to a greater civilization that pioneered in brick architecture. They excelled in the material palette of brick, timber & mud and created marvels that we label today as heritage. The material was purely natural/organic and the technology resilient. After each great earthquake, the past builders improvised the technology to enhance the resilience of the building but always taking advantage of the inherent strength of the natural material to their utmost extent. Anything that could not be achieved within the range of the strength of natural material was probably discarded and discontinued. Today a modern engineer might perform complex calculations or seek the help of modern software to analyze the behavior of these structures. However, for a traditional artisan, it was not only an interplay of stress and strain but also a manifestation of the divine integration of forces or energies. How would a modern engineer perform the structural analysis of a human body—all complete with structure, the infills and the systems? By the day we understand that the traditional structure is no different, we might have reached somewhere towards understanding traditional structure. Modern engineering and technology have their own realm where they can be at their best. In the realm of heritage, modern engineering should be better utilized as ‘supportive attendants’, and not as a grafted or overlaid knowledge to dictate or challenge traditional wisdom.

When Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap collapsed during the earthquake, it came down into a pile of debris killing 10 people alongside. At the time of the earthquake, a blood donation camp was being held inside. In the process of immediate rescue using heavy machinery, a lot of material was lost—one of the four main pillars (370x370 section) was sawn into two pieces, bricks and terracotta tiles were cleared from the site using JCVs, and other timber members were displaced haphazardly. Some of the carved timber members were salvaged later, and only a nominal number of bricks and roofing tiles could be saved only to serve as the sample for remanufacturing.

Two sizes of bricks were found to be used in Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap—the average size of the brick used in the ground floor was 24.5x16x5 mm, while that used on upper floors was 22x15x5 mm. Now it is a wonder why two sizes of bricks were used. Apart from other explanations, it indicates that the structure was so important as to make the builders go to the length of using two sizes of brick in the same structure—an instance that is rarely observed in other monuments. The large size of brick is already indicative of Licchavi era construction, which is reinforced by the fact that no stone boulders were found to be used beneath the brick walls in the foundation. At the time of laying the bricks later on, it was found that the wall thickness was derived from the module of the brick or vice versa. Again the brick was so proportioned that the brick mason could lay the bricks in whole without having to split the bricks anywhere. No closure brick was ever used in brick masonry. Bricks were laid in a typical bond of two courses in header followed by two courses in stretcher (named as Double English Cross Bond in modern terms). This type of bond was also observed in surviving bahā-bahi (Nevār Buddhist monasteries) with a history as old as the 5th century. Hence, it can be considered typical of the era, almost like a period detail. Somehow this type of bond is not observed in later period structures. Even the number of brick courses were placed based not only on structural grounds but also to mark various philosophical concepts in numerological terms. It is doubtless that these all signify not only an era of developed brick technology but also an era when the professional skills of designers and craftsmen thrived innovatively.

As these sizes of brick were uncommon and not readily found in the market these days, the samples salvaged from the site were sent for lab test and after scrutinizing the report, the executive team, in consultation with the experts, placed order for Remanufacturing.

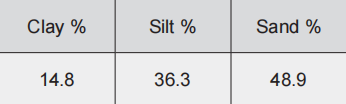

The mortar sample from the existing foundation was also sent for lab test and the report was quite exciting. The report revealed that the three major components of the mortar, viz. clay, silt and sand, were found in the following percentage: This was close to a ratio of 1:2:3 which was again a quite workable proportion. As it was prescribed that clay content reaching more than 20% is not good for the purpose of mortar because it makes the mortar brittle and flaky, the report was quite satisfactory in that respect. The search for the mortar soil with similar content was another challenge. Various samples of soil were sought and sent for lab test, however, with varying results. In the end, a mortar mix was devised by mixing two or three types of soil—soil with higher clay content to be balanced by mixing a calculated quantity of sandy and silty soil (pãcā). Prior to that, the report of archaeological study carried out by DoA and Durham University had also indicated a distinct possibility that the entire foundation might have been dug out initially; the foundation wall laid and the resulting chambers filled with silty mix of soil were quite different from the adjacent soil around. These show that the former builders were highly meticulous in choosing a specific type of soil for a specific purpose. It is needless to say that a quite developed soil technology might have existed in the past.

Source: KRC

Salwood was always the first choice for the timber used for structural purpose in traditional structures. We have very few monuments from the Licchavi period left to study and get an adequate idea of the building approach they followed in those days. However, instances demonstrate that the Licchavi period monuments are slightly colossal in their make; the size and section of timber used were slightly larger and the detailing bold. A famous hearsay has it that Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was built with the timber from a single tree. Considering the size of the monument and the quantity of timber required for its construction, it seems a distant possibility. However, it was observed that each of the four posts (370x370) on the central core, 32 posts (250x250) on the second layer and 28 posts (250x250) on the third layer on the ground floor were made from individual trees. Conversely, it can also be possible that the four central posts on the ground floor including the 16 meṭha-s (capital) and the 4 ninā-s (beams) on top of them could have been chiseled out from the one and the same tree. This argument can be based on the principle of seamless integration of caturmahābhūta, i.e four great elements, viz, air, fire, earth and water in the generation of all living entities, ultimately making them an independent whole in the making. And this might have triggered the above hearsay that ultimately took the form of a legend.

Fig. 3: The initial picture after the collapse (above); the immediate clearing operation after the earthquake. Photo: Maciej Dakowicz

Engaging community—the second pillar of heritage rebuilding

Community has always been thought to be the custodian of heritage. Moreover, cases have shown that the awareness of community about the heritage plays a vital role in shaping the course of action as far as conservation activities are concerned. It was in the case of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap itself that the community was against the tendering process that was initially being pushed by the government and the protest grew to an extent that the government was bound to change the decision. However, in cases where the community awareness on heritage is not so intense or even it is, if they do not voice against the malpractice, the conservation activities are seen to bring erroneous results and irreversible damages.

Throughout the reconstruction process, the community around Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap as well as the society at large was quite vigilant on what was going on inside. To make the activities transparent, only the wire mesh barriers were put up around the site instead of closing up totally restricting visual observation. Letting the community see the growth of the monument was crucial to establishing unseen link with the community that was significant in adding value to the monument. Needless to say, engaging community actively in the process of reconstruction was instrumental not only in adding value to the monument but also in instilling ownership of the community over the monument.

Volunteer participation of various community groups was sought at various stages during the reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. Hoisting the four main pillars on the ground floor with active participation of people from all classes of society marked an unprecedented event of forging close ties between Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap and the society at large. Engaging community and society in the event was a deliberate decision. After all, it was Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap that gave a name to this city.

Hoisting four main posts in place was thought to be the most challenging task of all. However, it was successfully carried out in the midst of a ceremonial event. Without any prior knowledge of how it was hoisted in the past, every possible way that could result in safer and quicker hoisting was discussed. Modern means like cranes and pulleys were also proposed, and quotations were called. But in the end, it was decided that no means other than by using non-modern and non-mechanical ways and by involving the community in the process will somehow enact the way it was hoisted in the past and will respect the tradition at the same time. The master carpenter and his team devised their own mechanism and everything was set up accordingly. A dense maze of bamboo scaffold was pulled up within a week or so, ropes were set in place and the community volunteers eagerly stood ready for the posts to be arrived. Transporting the posts from the workshop at Hanumandhoka from where they were being prepared at some 200 meters from the site was another mammoth task. Members of various guṭhī-s, musical troops and societies, who were invited to volunteer, carried the posts from the workshop to the site in a grand procession. Finally, the hoisting was carried out sequentially in the middle of hooting and cheering and with the jovial participation of all groups of citizens. It was believed that the event added a noble value to the reconstruction process of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap.

The community was seen to be quite resilient in that the postearthquake trauma could not deter the community from carrying out yearly jātrā-s, festivals and celebrations. Not a single festival was halted and all the yearly rituals performed in and around Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap were steadfastly carried out even in the midst of the chaos of reconstruction. In one of the celebrations namely Pañcadān / Pañjarā (Nevār) celebrated on Bhādra Kṛṣṇa Trayodaśī every year, the members of Taḥ Catã Guṭhī associated with the Tāmrākār community that resides close to Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap, take a huge copper cauldron inside Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap the day before cooking khīr (rice pudding) over the heat of firewood, and they will keep it overnight inside one of the pavilion rooms (generally the one on the north-west) on the ground floor of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap and give it away the next day to those coming for Pañjarā, a culture in which people pay a visit to various places seeking donations which necessarily includes five types of grains apart from other items.

The next ritual carried out by Sā Guṭhī, associated with Ḍaṅgol community of Bhimsensthan close by, is celebrated on the 1st of Māgha every year. During this ritual, the members of guṭhī take a copper cauldron inside Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap the day before boiling a prescribed quantity of wheat, which is kept overnight inside one of the pavilion rooms (generally one on the north-west) on the ground floor. On the next day, i.e. on the 1st of Māgha, they perform an elaborate tantric ritual on the ḍabalī to the south of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap, feed the boiled wheat to the cow, and finally the members go up to the pinnacle to raise a flag and strew down yomarī and locāmarī for the observers on the ground to find a catch if they are fortunate enough. By tradition, there is a queer practice at the end in which a member on the top asks aloud if the price of salt and that of oil has been equalized for the year. It is still not quite clear what the actual implication of this practice is. Besides its literal connotation, it can equally be viewed as a codified analogy to some other idea. Reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was one thing, but there are myriad of other things associated with Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap that still require insightful research work.

These rituals were steadfastly carried out on the assigned dates throughout the period of three and a half years of reconstruction. Such resilience of the community especially in carrying out the festivals is also seen to provide impetus for the heritage rebuilding process.

Fig. 4: The dense maze of bamboo scaffold was put up to aid the hoisting of the posts (top left) Photo: KRC; The post being positioned before hoisting (top right) Photo: Sugat Tamrakar; The post being carried to the site (bottom left) Photo: Social Media; The hoisting of the posts using traditional method (bottom left) Photo: Sugat Tamrakar

Fig. 5: After the reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap, people coming to receive pañjarā are made to sit around the four central posts and the khīr (rice pudding) cooked the day before is distributed. Photo: Shailesh Rajbhandari.

Fig. 6: The wheat is boiled inside Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap the day before and after performing elaborate ritual the next day on Māgha 1st, and it is fed to the cow. Hence the guṭhī is named as Sā Guṭhī (Sā is cow in Nevār dialect) Photo: Shailesh Rajbhandari

Livingness of Nevār heritage

The term ‘Living Heritage’ is often used in relation to the human activities associated with a specific heritage structure. This is interpreted in terms of associated rituals, festivals, customs, etc. that necessarily exhibit one or other kinds of human activities. However, the concept of livingness is entirely different as far as Nevār heritage is concerned. In Nevār ideology, a heritage structure is considered to be a living entity, as alive as a human being, in that the heritage structure goes through an elaborate process of ritual generation in its making, almost like the evolution of a living entity. Many a time, the rites that a living person goes through at various stages of his/her lifetime are also ritually followed for the structure in the making. For instance, whenever the central yasĩ of Svayambhū stupa is replaced, tradition shows that the old yasĩ is subjected to a funeral rite similar to that of a person.

A series of rituals were performed during the reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap enshrining all the integral entities layer by layer after the completion of each crucial stage. This might not make so much sense to everyone, but these are the very elements that render true value to the heritage. At the end of the day, we may wonder what purpose these heritage structures actually serve. The answer may lie in these very subtleties. It is needless to say that those who overlook these things are stuck with the lump of inert building materials and might think that the answer may lie in interpreting the layers of history—an idea entirely based on the notion of dead monuments.

The cases of damage, dilapidation, collapse or even change in the fabric or style affecting the original identity or character of a heritage structure can be marked as the declined glory of a living entity. In this respect, heritage conservation can be interpreted as the act of reinstating its former glory, which might have been lost because of some catastrophe, the misjudgment or indifference towards the original identity of the structure, or probably because of some whimsical ideas of an adamant ruler. Given that, reusing old elements might be seen as grafting the original gene to the heritage structure and reverting to its original fabric or style, as a glorious uplift of its persona.

Study on the design of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap

There is a legendary story associated with the construction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap, wherein a divine tree namely Kalpavṛkṣa in the form of a human was identified and leashed with tantric powers while he was attending a jātrā and his release was bargained against the wood required for the construction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. Even when the reconstruction was over, he was cleverly made to stay close until the moment when the price of salt and oil were equalized in the market. This is demonstrated during the aforementioned ritual carried out by Sā Guṭhī every year in which a person while on the top of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap asks the question aloud and if it is found otherwise, it is believed that the Kalpavṛkṣa will stay close for yet another year. Not to mention, these legendary narratives could again be a codified analogy to some other concepts.

Tantric practitioners agree that Nepal, and especially the Kathmandu valley, has always been a potent site for performing sādhanā. Kathmandu valley has been enriched with several energy centres and spots as a result of sadhana carried out by various siddhas and practitioners throughout the centuries. In that respect, the whole of the valley and surrounding area has been envisaged in the form of a maṇḍal (however, not in a strict geometric sense), which is considered a crucial tool while performing sādhanā. This has developed into an idea of Nepāl Maṇḍal, in the grand scheme of which all the energy centres and spots find their due space in assigned hierarchies. This is the macrocosmic projection of maṇḍal in space, while the microcosmic projection is also made into the self as various energy plexus in the body and sādhanā performed accordingly. Such projections were made at various levels and even liturgical connotations were apparently developed with complementary themes. Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap can be viewed along the same line. The respect paid by siddhas like Gorakhnath could not be otherwise.

As the architectural proportion of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap is a bit different from that of other temples, one may infer that it might have been designed based on a different proportioning principle. The study made during CRK period as well as during the initial phase of reconstruction revealed that the actual design and proportion of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was found to be numerologically guided, believed to be linked to Vajrayana principles. The core structure of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was believed to have been designed to fit into a cuboid of a side measuring 36 cubits (hasta) in length. Hasta was the unit of measurement commonly used in those days, and only by converting the modern metric measurements into hasta measures were the various numerological associations discovered, as almost all of them resulted in whole integers. With iteration, it was found that the type of hasta unit followed in Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was kiṣku hasta (1 hasta = 24 aṅgula = 42.7 cm). The length and breadth of the 36 hasta cuboid were measured against the length of the second layer foundation wall (dated to belong to the 9th century), while the height was measured from the plinth up to the bottom of the pinnacle. Such numerological prescriptions were found not only in the measurements but also in determining the number of various building elements, such as the number of brick courses at various locations, the number of posts on various levels, the number of joists and rafters used, and so on. E.g. it was required that the number of joists over the four central pillars has to be ten in number—believed to symbolize ten pāramitā-s; the number of risers (33) of stair on the ground floor reflected the number of vertebrae in human spine, etc. The number of posts on each floor, i.e. 100 on the ground floor, 64 on the first floor and 20 on the top floor, was all numerologically assigned, representing each deity, forming a maṇḍal in conception. The height of each floor, the detailing of the niches, and the detailing of the pinnacle were all found to be strictly guided and were ritually invoked on par with the sanctity of a maṇḍal. The earlier misconception that Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap was a sattal (rest house) was hence cleared—at least for those involved with the reconstruction.

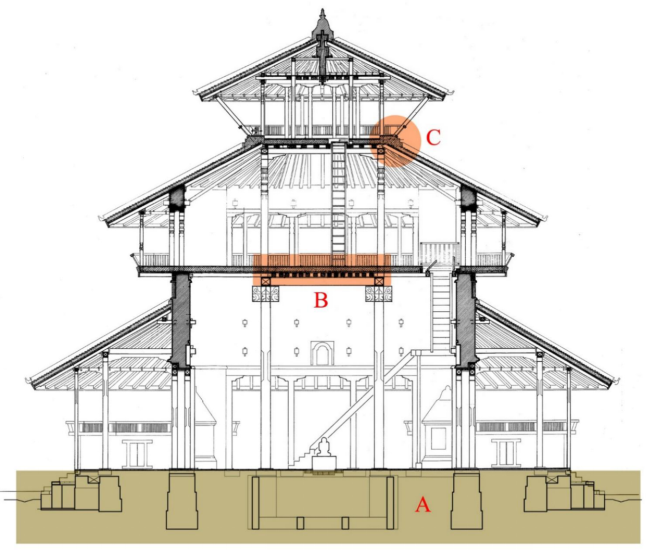

Fig . 7 : Section Drawing (after Korn:1998) of earlier version of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap. (A) The details of foundation, which was missing earlier, were revealed from the archaeological investigation carried out by DoA/Durham University. (B) The anomalous details found in earlier drawings, e.g. the central joists have to be 10 in numbers, were corrected. (C) The details of embedded structural members, which were missing previously, were rigorously developed and implemented.

Observation on other reconstruction models

Reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap took place at an unprecedented time and under special provision. After a satisfactory reconstruction of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap, it was voiced that a similar approach needs to be adopted for other conservation projects as well, but without any avail yet. The observation on the approach adopted in the following two projects will demonstrate that it is still a long journey in instilling heritage sensitivity among administrators and bureaucrats who are in a position of decision making.

The first is the reconstruction of Gustala Mahāvihāra in Patan. , implemented by the Central Level Project Implementation Unit (CLPIU) under NRA, but funded by the Government of India (GoI) and technically designed and supervised by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH). INTACH hired local experts to advise them on the technical issues. However, the work was seen to be carried out with little heritage sensitivity. The original mud mortar was ruled out from the very outset and replaced with lime mortar. And even if they resorted to timber and brick as principle building material, the robust technique they adopted for structural strengthening invariably following the idea of concrete technology was quite contrary to the nature of traditional structure. With the common voice from prominent heritage professionals, the team was made to be aware that the details proposed were detrimental to the essence of traditional technology. However, they remained adamant in pushing the proposed details ahead, probably because of the national prestige issue of the concerned donor. The DoA remained at low key since the project was initially run by the NRA, and apparently there was a tacit understanding that DoA would not interfere with whatsoever matter the NRA undertakes. NRA was seemingly established with higher authority that could overrule the existing regulations if it deems necessary. All the existing heritage regulations and heritage sensitivity, for that matter, were jeopardized in the process.

The second project is the reconstruction of Brahma Temple at Jayavāgiśvarī in Kathmandu. Only the foundation of the temple was intact, yet covered with various layers of subsequent additions over the decades. Upon clearing, the original foundation was revealed to be built in mud mortar with the bricks of size 33x22x5 cm. As this size of brick is uncommon in later structures, it was assessed that the structure might belong to an earlier period. Moreover, the statue of the deity, that was housed at a separate location, was featured in the publication namely ‘Stolen Images of Nepal’ wherein the author Lain Singh Bangdel had dated it to the 6th century based on its stylistic features. These observations showed that the temple is quite old and has high heritage value. The concerned authorities were made to be aware of the gravity of the situation and sincerely advised that the brick with similar size needs to be manufactured for reconstruction. However, when the project was later tendered by the local authority, the whole idea of brick manufacturing was abandoned under the pretext that it would prolong the process and incur delays in reconstruction. And by the time this paper is being prepared, the reconstruction has already begun with the bricks of different size commonly available in the market.

These are only few representative cases. There are numerous instances where the lack of heritage sensitivity on the part of administrators and bureaucrats has put the value of several heritage structures at stake in the past. In this respect, the model adopted for Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap can be viewed as exceptional, which does not exactly correspond with any of the currently existing models. It has almost been ten years since Nepalese society has suffered the trauma of 2015 Gorkha earthquake. Several heritage reconstruction and renovation projects have been carried out over the decade—some with good outcomes, while a lot of them criticized for the anomalous approach followed therein. It is a pity that the concerned authorities have failed to learn the lesson even after a decade of wider experience in these areas and not even a hint of sensitivity is yet seen towards preserving the essence of heritage. We can only be hopeful that amendments in existing provisions will be made some day and models that will work towards preserving the value of heritage structures will be formulated and officially adopted.

Fig. 8: Heavy timber reinforcements imposed in contrary to the nature of traditional structure. Photo: Gyanendra Shakya

Fig. 9: The foundation of Brahma temple revealed after clearing the site (left) Photo: Binita Magaiya; The statue of Brahma (right). Photo: Author

Conclusion and recommendation

When we, as heritage professionals, enter the realm of heritage conservation, we should bear in mind that we are going to intervene with somebody else’s creation, which is quite sensitive topic and demands humility on our part. And there is no point in grafting foreign or even personal ideas and concepts onto those of the first creator. Heritage might have lost its glory along the passage of time in the form of structural collapse, damage, dilapidation and change in its original fabric or even form. It is needless to debate on the idea of originality if we can reflect for a moment on the intents of the first person. True conservation might lie in reinstating the original glory of the monument. Instead of delving into any of the modern theories and principles, the only guidance to seek would be to ask whether the first person would be happy with whatever we would do to his/her creation.

The strength of heritage structures has always been a topic of discussion among professionals. However, heritage structures should not be judged solely on structural grounds. As it is rightly said that one should not judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, one should realize that the traditional structures are no match against rcc or any other modern structural system. All of them are to be judged against their own inherent nature, and it is not fair to cross-match them with each other. Besides, there are a whole lot of other parameters that are to be considered as far as the value of heritage is concerned.

In defining the reality with respect to heritage, people resort to the novice idea derived from Buddhist scriptures wherein the reality is symbolized as an elephant fumbled by different blind people each coming up with a different perception of what it is. Finding the true nature of heritage, however, is as strenuous a task as the sādhanā of a deity with multiple arms and complex imagery. At some point in time, this may even require self-dissolution into the edifice itself—a moment that is beyond any explanation. All heritage edifices are essentially the embodiment of knowledge in diverse ways. Even then, they are just the ‘fingers pointing to the moon’. And it must be the ‘moon’ that the first person would have liked the society to make an effort to seek.

Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap unfolded itself with new meaning and created a dialogue that was heard and diligently responded to by everyone involved. The underpinning guide and ever-present support for its meaningful reconstruction were always found within the folds of the community. The memory of something that was lost was so strong that craving for the associations with its earlier physical form was always felt. However, this craving gradually subdued as Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap slowly took shape. Community remained as ever-present custodian to the monument and its liveliness; the people who came together in this frame of time and space in rebuilding Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap were mere causation/means on behalf (nimitta); while the real heroes had already gone unsung and Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap flowed in the perennial stream of time to future or even to the next dimension.

loading......

loading......