Author

Sabina TANDUKAR

Principal Architect, Habitus Creations, Lecturer, Himalaya College of Engineering, Tribhuvan University

Email: sabina3520@gmail.com

Abstract

In the aftermath of the 2015 Nepal earthquake, the country faced not only the tragic loss of lives but also a huge threat to its architectural and cultural heritage, particularly within the Kathmandu Valley’s historic zones and surrounding settlements. While national and international attention was focused on major monuments within World Heritage Sites, many traditional settlements and historic private houses were overlooked. That led to widespread dismantling and rebuilding with non-contextual concrete structures. This paper presents grassroots initiatives like the Traditional Building Inventory (TBI), formed by volunteers to document the earthquake-damaged as well as remaining built heritage. It discusses the systemic challenges of post-disaster reconstruction. These include insuffcient fnancial incentives, incompatible building codes, a shortage of skilled manpower, and a national policy that faintly supports heritage-sensitive restoration. The case studies of Bungamati, Sunaguthi, Patan, and Dhulikhel illustrate that the willingness and capacity of local governments play a decisive role in safeguarding historic urban landscapes. It argues that effective conservation requires placing the needs of residents at the core of policy-making, offering incentives, guidance, and infrastructural support. The paper calls for a shift from top-down reconstruction approaches to inclusive, locally-driven urban conservation, emphasizing the preservation of their identity, historicity, authenticity, and place memory.

Keywords

Post-earthquake reconstruction, Local government, Historic settlements, Heritage-sensitive restoration, Policy and planning

Introduction

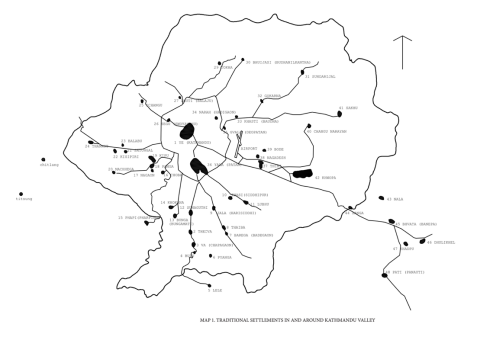

In the wake of the 2015 earthquake, Nepal lost not only human lives but also its cultural heritage, which was at stake of erasure. Numerous monuments, big and small, had collapsed, and even more had sustained signifcant damage. At this hour, the national and international focus was on major monuments, mostly on World Heritage Sites (WHS). The historic settlements with few monuments and many historic private houses were silently fading into oblivion. However, there were activities felt and voices heard to preserve what was left of historic settlements. There are altogether 52 big and small historic settlements in the Kathmandu Valley, including a few from Kavre and Chitlang Valley. These often portray similar characteristics in terms of their topographical placements, often placed at highland and surrounded by agricultural lands and rivers fowing by. These dense and compact settlements have an urban agrarian nature, whereby they embody both tangible and intangible attributes and deeply embedded cultural values.

Traditional building inventory (TBI)—a volunteer group that documented 32 historic settlements

In the aftermath of the 2015 earthquake, frequent visits to Patan Durbar Square brought together a small group of concerned heritage professionals. During these meetings, we often debated the future of Nepal’s historic urban fabric. One such discussion proved pivotal—when Padma Sundar Maharjan and I visited Thankot’s historic settlement, we encountered a sobering reality: numerous damaged houses stood on the verge of being dismantled by their owners. The sight flled us with urgency.

Realizing these structures might soon vanish forever, we hastily documented them through photographs. Our return journey became an impassioned discussion about the critical need for systematic visual documentation of endangered heritage. This experience later catalyzed an offcial initiative at the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) to rapidly survey and record the vanishing architecture of Kathmandu Valley’s historic settlements. Heritage expert Dr. Rohit Ranjitkar, Senior conservation Architect Sirish Bhatt, Dr. Neel Kamal Chapagain, Padma Sundar Maharjan, Monica Bassi, and I devised a quick documentation form and opened a Facebook page where we called for volunteers to support this cause. A huge support was instantly felt as hundreds of young volunteers, mainly comprising architecture students and heritage enthusiasts, came forward and helped with rapid documentation of settlements that were near to their place of residence. This was obvious at the time when the very thought that the earth below our feet could shake any moment made most of us anxious and alert too! The initiative was supported by Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) in the frst place by providing space for meetings. Later, ICOMOS Nepal also supported the cause. During times when a blockade was imposed on Nepal and there was a scarcity of fuel and when most eateries were closed for the same cause of fuel scarcity, our team travelled to distant settlements and documented what was to be seen for the last time—the historic urban fabric! We even documented the historic settlement of Chitlang, which was the farthest we could go. The fnal documentation was submitted to UNESCO, as the project was partially funded to support the volunteers with basic logistics like printing, pens, paper, clipboards, survey forms, etc.

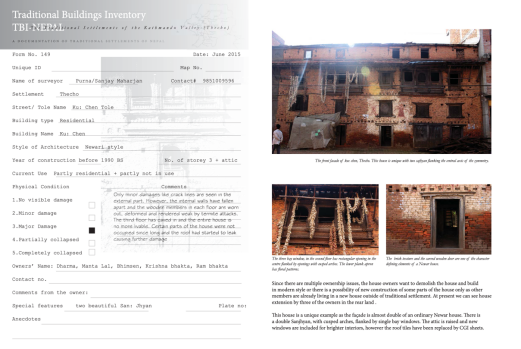

Fig. 1 A sample of TBI survey form and photo documentation of a historic house from Thecva, Lalitpur

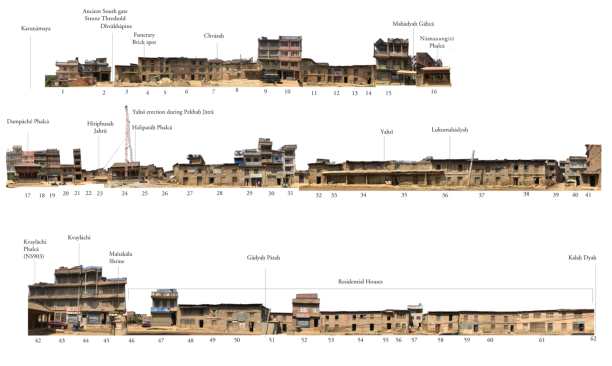

Fig. 2 Houses along the main street at Sunaguthi (Source: Padma Sundar Maharjan)

Dismantling of historic houses and construction of concrete structures in their place

While the historic settlements were being rapidly documented, the earthquake-damaged houses were also being quickly pulled down. And soon new constructions started to be seen. But alas, the new houses did not in any way match the historic house that stood before. The government initiated the recovery and restoration process with the slogan ‘Build Back Better’, but there was no policy or mechanism to encourage historic house owners to preserve their houses. Nepal Reconstruction Authority (NRA) was established in December 2015, eight months after the earthquake, for the same purpose. The NRA began the owner-driven housing construction program after the launch of the Post Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA). The program included a housing construction grant of NRs 300,000, provided by the Government of Nepal (GoN) in three trenches linked to compliant construction; NRs 50,000 upon signing the partnership agreement with the GoN, a further NRs 150,000 after completing the foundation works, and a fnal NRs 100,000 after completing the walls. The construction compliance catalogue, which included a design catalogue for the reconstruction of earthquake-resistant houses, was published by NRA in two volumes. Volume I included a single typology of brick masonry in mud mortar, but the design was of a single-storey structure and did not do justice to traditional three- or four-story mud mortar-brick masonry houses of Kathmandu. For houses identifed to be ft for use after structural retroftting was disbursed a grant amount of NRs. 100,000. The grant amount was released through the District Level Project Implementation Unit (DLPIU). In any case, the amount was not enough for heritage-sensitive restoration. Besides, the typologies of seismically resilient houses put forth by the NRA clearly promoted cement mortar-based construction with several horizontal and vertical tie bands, and failed to cater to the traditional historic houses. UN-Habitat Nepal worked in Bungamati and published ‘Bungamati Area Reconstruction and Development (BARDeC) Citizen Charter’, where it mentioned its primary priority as the reconstruction of private historic houses in its original design and proportion, and in using traditional materials. The initial cost estimate shared by the team for a reconstruction of a three-storey attic—a typical Newar—was approx. 70 lakh rupees.

A study of one such settlement, Bungamati, was carried out by Dr. Rohit Jigyasu with the support of Ritsumeikan University, Japan, for which I had an opportunity to be part of the feld data collection team. Those several visits to sites and structured interviews with the houseowners gave a glimpse of what the villagers valued most. There was an identity crisis among the inhabitants, both young and elderly. They saw their monuments collapse, and they thought their identity was also at stake. In response to housing issues, there was a common voice that they want to retain their historic fabric, but they also want a concrete structure that would behave better in future earthquakes. This was also because they saw their old houses crumble down while their neighbors’ concrete houses did not suffer much. It is also important to mention here that the National Building Code (NBC) of Nepal does not qualify any houses built in mud mortar, nor does it identify houses more than three storeys and having timber foors to get any form of building permit. This lack of a scientifc approach to validate the load-bearing houses, made in mud mortar and having timber elements, became detrimental to the valley’s historic urban landscapes.

When the concrete structures were built, house owners tried to make a brick façade, and windows were placed in odd numbers to maintain the axial symmetry. However, the detail and artistry in cornices and pilasters were lost. The proportion and deep relief carving works common in traditional doors and windows were lost, and during reconstruction in concrete, the foor height was increased, which again did not help in maintaining the façade proportions, and moreover, the jhingati tiled slope roof was replaced by fat terraces. In many cases, only skirt roofs remained running along the perimeter of its parapet walls. In totality, the fabric was lost!

The same was the case in almost all historic settlements; heritage professionals like us had utterly failed to convince these historic house owners to preserve their houses. The question of ‘Are traditional houses seismically safe?’ was unanswerable. Well, the same goes for concrete houses too because no expert can say when and what magnitude earthquake will strike and what damage it will cause to concrete structures!

Practicing architects and engineers seemed not well trained in heritage-sensitive reconstruction works, and as such, it harmed the built environment. Lack of skilled manpower and high daily wages of a few existing skilled building craftsmen were responsible for such pitiful reconstruction. And to add to the mayhem, the road expansion project planned by Kathmandu Valley Development Authority (KVDA) through the historic settlements was a hard blow to all efforts made towards urban conservation. For instance, Kantilokpath passed through historic settlements like Sunaguthi, Thecho, Chapagaun, cutting right through the heart of the settlement, demanding an 11m right of way (R.O.W), which would mean entire settlements like Sunaguthi and Chapagaun would be displaced and their tangible/intangible attributes lost. And today, 10 years after the 2015 earthquake, we see that locals have not dared to rebuild their historic house for fear that the government will one day bulldoze their houses. A house in Nepal is a person’s lifetime earnings and savings. The old houses along the main street of these historic settlements remain half collapsed and with vegetative growth and dust overtaking them. Is this what a government can do to preserve its cultural asset? If there is a right to a road, then what about the right of a citizen to shelter? Or what about the right of a heritage house? Why should a settlement with the written inscription of more than a thousand years ago succumb to a 40-year-old institution with its top-down mandate to make roads for vehicles and not cities for people? The Ancient Preservation Act, 1956 defnes any object or structure more than 100 years old as heritage and defnes strict punishment procedures for anyone or any institution who dares to destroy, demolish, remove, alter, deface, or steal such heritage.

The other issue felt post-earthquake was the unscientifc support given by local political groups. In Sunaguthi, members of the local political group, with the intention to help the earthquake victims, came up with the idea to help the owners demolish the houses. And in that chaotic situation, everyone geared together to pull down the historic houses that could have been retroftted and rebuilt because the beauty of traditional masonry houses is always the opportunity it gives to repair and maintain them, part by part. Even the foundation could be rebuilt using underpinning methods. Lack of knowledge and institutional setup was felt, which could have otherwise guided everyone during those hard times. In yet another case of Dhulikhel, historic houses with multiple owners took this as an opportunity to demolish standing historic houses to divide the land among themselves!

Fig. 3 The sattal situated on the right of the main entry to the machindra bahal. The roof caved in and the entire foor and rear wall collapsed

Fig. 4 A house at Machindra bahal had one of its wall in sun dried bricks which was not tied properly to its front wall. The side wall bricks eroded during the violent shaking

Fig. 5 An earthquake-damaged house at Chohel nani was quickly demolished and concrete structure work started. The family when interviewed were affuent poeple of the locality as such they could afford faster reconstruction

The formation of local government and the recognition of the need to preserve historic houses

Before federalism, Nepal had a centralized government, so the 2015 constitution was a signifcant shift. It mandates three tiers of government—federal, provincial, and local—ensuring decentralization of power. Nepal also saw the formulation of the Local Government Act 2017, which also talks about the historic settlements in articles 9.1, 9.2, and 9.3. This act gives the right to all local government bodies to identify, nominate, and certify the historic settlements within their administrative authority and gives the right to allocate funds for the preservation of their heritage sites and settlements. Besides, Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration (MoFAGA) also issued ‘Basic Standards on Settlement Development, Urban Planning and Building Construction’, whose 14 A section specially talks about provisions made on all construction works within historic settlements and aims for preservation of the historic urban fabric. This is part of the byelaws for all municipalities now, and as such, a clear guide to municipality engineers and the house owners alike towards what is expected of the historic house reconstruction. But then again, there is a need for guidelines that could guide house owners and architects step-by-step in the repair and maintenance of the existing historic houses. This is crucial because although we lost so many of them but there are still many that are standing and waiting for purposeful restoration.

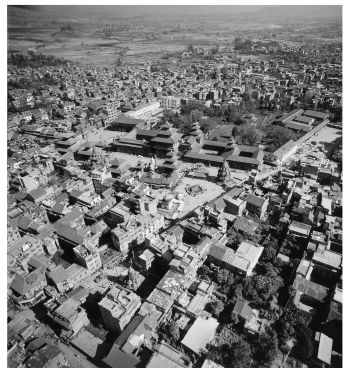

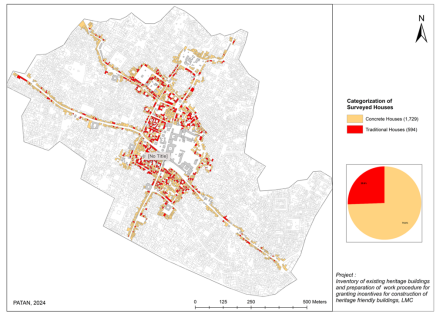

For instance, in 2024, Lalitpur metropolitan city conducted a study of existing historic private houses within its World Heritage Zone to prepare a detailed inventory, drawing documentation of selected historic private houses, and prepare a work procedure to provide an incentive mechanism for restoration, repair, and maintenance of listed houses. The study documented 594 historic houses within its WHS zone, which accounted for one-fourth of the total housing of the area, of which two-thirds are still being used for residential purpose. A detailed condition assessment of the remaining historic houses shows that only 1/4th of the 594 houses sustained major structural damage, which means these houses might need to be partially or fully dismantled for the purpose of structural safety. This data clearly shows that the remaining 3/4th houses could be repaired and maintained without dismantling them. The municipality plans to promote the restoration of existing historic houses in Phase 1 rather than investing in the construction of new houses in traditional style. Such initiatives to document and develop mechanisms to fnancially support private house restoration is vital for urban conservation.

Such a mechanism is already being exercised by Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC). In such an endeavor, KMC also nominated the Lichchavi Capital of Nepal—Handigaon as the historic area and has prepared several plans of action to revitalize its historic and archaeological areas. Handigaon has extant cultural practices, several monuments, and an important archaeological site of Satya Narayan. All plans of action in these areas need to be scrutinized so that their vitality does not diminish. However, the area does not have a signifcant number of historic houses. Modern concrete constructions seem to have taken over ancient Handigaon, and KMC is adamant on at least reworking with facades of these houses to recreate their ancient outlook.

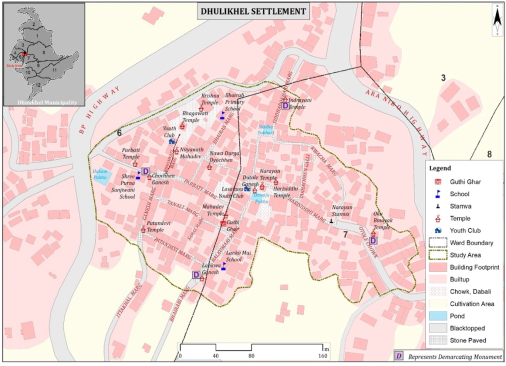

The other similar example is with Dhulikhel municipality, where it is also preparing plans to preserve and revitalize its ancient settlements of Dhulikhel and Khadpu. The problem with Dhulikhel and Khadpu is the outmigration of their local population, leaving the houses within the settlement vacant, abandoned, or rented. The sample survey of Dhulikhel shows that 70% of the households had either some or all the members of the family migrating to other places outside of Dhulikhel for employment, business, and education. The fndings of this study (2022-2023) conducted by the municipality show that Dhulikhel has 41.8% traditional houses, and 99% ownership of houses is with the locals and 36% of the residents of historic houses were willing to preserve their historic houses provided the interior functions are changed as per their modern lifestyle and if municipality would provide some fnancial incentive and recognize their efforts. The municipality here is looking for plans of action for not only restoring historic houses but also fnding ways for economic revitalization, such that the restoration becomes sustainable.

These three cases of the local municipalities show that the willingness of local government to preserve its historic setting is the frst indicator towards the potential preservation and revitalization of historic settlements. When the local government is determined, it can often fnd ways to work with the locals to achieve the common goals of preservation of the historic urban landscape. However, having said that, the other crucial task for local government is to build staff capacity and cultivate industry professionals for heritage-sensitive construction works.

Fig. 6 Patan, aerial view of Mangal Bazar, and Darbār Square, featuring the palace complex, from the south-west. Photograph R. Kostka, November 1986

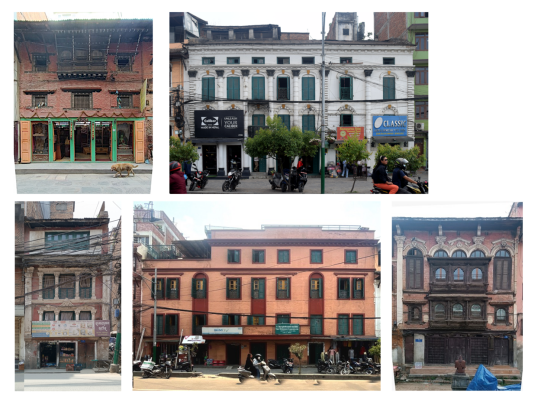

Fig. 7 Historic houses from Patan WHS that are still intact in its design and overall composition

Fig. 8 GIS map of Dhulikhel settelment

Fig. 9 Development of distinct architectural characteristic of historic private houses standing along the main streets of Dhulikhel

Needs assessment of the historic house owners

The satisfaction of stakeholders, local communal groups, and house owners is a determining factor in all urban conservation works. The locals feel satisfed when their voices are heard and when they are included in decision-making. This is where the collaboration between local government and local stakeholder groups needs to be bridged. The imposition of restrictive laws for heritage house owners based on assessment of the tangible-built fabric and without evaluating their social, cultural, and economic needs could mean that the settlement preservation and revitalization efforts will not be sustainable. For instance, 33% of households in Dhulikhel were reluctant to preserve their historic houses; rather, they wanted to construct a concrete structure in their place. One of the many reasons is that the current incentive provided by the municipality is not suffcient, and the administrative process to receive the amount is complicated. Another reason is the space needed for the growing family, which could be fulflled by adding foors. Yet another reason is that they are not aware of the cultural and economic benefts that the historic house could bring to them, besides achieving a quality life when the entire settlement is revitalized.

In Lalitpur Metropolis, during documentation of historic houses, the house owners shared that they could not ft their contemporary lifestyle in their old houses, such as having a proper bathroom on each foor or adequate daylight into the interiors, as well as ventilation issues. In yet another case, due to rising road levels, the ground foor was always inundated during urban fooding. The other pressing issue were the vertically divided house, where only a narrow slit of old house remains with tall concrete structures on either side. This has increased the vulnerability of the remaining old house. Practical solutions for such issues need to be provided for house owners so that they can lead a quality life in their historic houses.

Conclusion

The preservation of historic private houses is a prerequisite for the revitalization of any historic setting. As such, it is crucial to place the needs and aspirations of residents of these houses at the heart of all conservation and policy-making works. At the local government level, it seems that the very recognition of these houses is the frst step towards heritage preservation and a positive encouragement to house owners. Besides, it is high time that the local government, with so much authority, tried to challenge decisions and policies that adversely impact heritage settlements. A local citizen should not feel alone and helpless in front of a long list of rules and restrictions; rather, the local government should and can play the role of guardian in protecting the rights of its citizens and its heritage. The role of local governments in making the historic settlements safer and also preserving their identity, historicity, authenticity and place memory in times of disasters is very much needed. At the end of the day, urban conservation is not about freezing time!

loading......

loading......