Author

Nazmi ANUAR, School of Architecture, Building & Design, Taylor's University, E9A, Email: AhmadNazmi.MohamedAnuar@taylors.edu.my

Nazmi Anuar is a partner at the research practice E9A and teaches at the School of Architecture, Building and Design, Taylor's University. His research interest is in the relationship between architectural form and the city. Nazmi Anuar holds a Bachelor of Architecture from Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) and a Postgraduate Masters in Architecture and Urban Design from The Berlage, TU Delft. He is the author of the book Background Frame Platform (2021) and co-author (with E9A) of the book Between Rail and River: Notes In Time On Kluang (2025).

Abstract

The city of Kuala Lumpur could be read as an agglomeration of large-scale developments. With their detachment from the immediate context, these developments – such as Mid Valley City, KL Eco City, Empire City etc. - could be read as isolated “city within the city” or “urban islands” which together generate the peculiar archipelago urbanization of Kuala Lumpur, where the city is fragmented and made up of the accumulation of many smaller cities. Kuala Lumpur is becoming a playground of speculative large-scale commercial development. Therefore, this article aims to explore this phenomenon in relation to an overview of neoliberal urbanization and the idea of the city as an archipelago based on theoretical methodology. Through a critical review of related theories and literature, the study identified the point of emergence of large-scale developments in Kuala Lumpur, their key characteristics and their possible impact of the physical and social fabric of the city.

Keywords

Neoliberalism, Neoliberal urbanization, City within the city, Urban islands, Archipelago city

1. Notes on Neoliberalism

1.1 The Developmental State: Neoliberalism and Malaysia

In his landmark study A Brief History of Neoliberalism, David Harvey defined neoliberalism as “a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade” (Harvey 2005). Neoliberalism can also be understood as the intrusion of market dynamics into all aspects of life (Springer, Birch, and MacLeavy 2016) as a “new political, economic, and social arrangements within society that emphasize market relations, re-tasking the role of the state, and individual responsibility” (Springer, Birch, and Macleavy 2016) and a “political belief in the primacy of the market for governing human affairs” (Cupers, Gabrielsson, and Mattson 2020). In practice, neoliberalism has been commonly associated with market-oriented policies which have been linked with various socio-political ills (Springer 2017).

Rather than a case of erosion of state power in the face of market forces - as is prevalent in the West - the Malaysian version of neoliberalism maintains and expands state power through active collaboration between the forces of the market and the “developmental state”, which is defined as “the state that is understood to have prioritized national resources for investment in nurturing targeted industries through bureaucratic systems while maintaining state-led development of the market” (Chen and Shin 2019b). Malaysia’s shift into the developmental state approach was dated by Chareonwongsak to the implementation of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1971 (Chareonwongsak 2021). Implemented in 1971 for economic restructuring after the racial riots of May 1969, the NEP has been argued to reveal “the determination of the government to enact quasi-neoliberal policies before the era of neoliberalism came to dominate the West” (Tedong, Grant, and Wan Abd Aziz 2015). Through the NEP, measures such as privatization and affirmative action were introduced to improve the economic standing of the Malays while furthering the interests of politicians and the elites (Tedong, Grant, and Wan Abd Aziz 2015).

The entrenchment of neoliberalism as an economic ideology could be traced to the first administration of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed (prime minister: 1981 – 2003) who instituted practices such as privatization, free market policies and financial liberalization (Tedong, Grant, and Wan Abd Aziz 2015). The Fifth Malaysia Plan (1985 – 1990) launched what is referred to as Mahathir’s “authoritarian neoliberalism” (Juego 2018), which is a mix of “authoritarianism, crony capitalism, and neoliberalism” implemented through “patronage politics, authoritarianism, and economic restructuring” (Juego 2018). As we shall see, the effects of neoliberalism on the urban fabric manifested itself in the 1990s (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022).

1.2 Growth First: Neoliberal Urbanization and Kuala Lumpur

The link between the ideology of neoliberalism and the processes of urbanization was first identified by David Harvey in his seminal essay “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism” (Harvey 1989). Harvey argued how urbanization processes are shaped by capital circulation and accumulation, where there is a shift in urban governance from a focus on public good towards public–private partnerships and profit-driven agendas (U. Rossi and Vanolo 2015). Meanwhile, Neil Brenner, Jamie Peck and Nik Theodore elaborated how neoliberal urbanization can be defined as a process of market-driven urban development or transformation, guided by the political economic theory of neoliberalism. (Brenner and Theodore 2005). The scholars also introduced the concept of “creative destruction” to describe the “geographically uneven, socially regressive, and politically volatile trajectories of institutional/spatial change” occurring under neoliberalism (Brenner and Theodore 2002).

Guy Baeten further identified some of the “neoliberal planning policies and tools” as including the rise of Urban Development Projects, often carried out through forms of Public Private Partnerships (Baeten 2018). Baeten sees Urban Development Projects as a template for establishing new city districts, with a “a mix of housing, offices, signature architecture, shopping malls, transport facilities, exhibition halls and cultural centres” (Baeten 2018). Private Partnerships are meanwhile seen as providing access for the private sector to public funding, while serving corporate interests. Baeten also noted how these projects are often disconnected from the rest of the urban fabric and are contributing to polarization within cities by displacing former inhabitants (Baeten 2018). Writing along similar lines, Chen and Shin noted how the pervasiveness of terms such as “urban redevelopment, regeneration, renewal, or renaissance” in urban policies could be linked to the hegemony of neoliberal urbanization through a heavier reliance on property development as the driver of growth (Chen and Shin 2019a).

Today, neoliberal urbanization is manifested in the city of Kuala Lumpur as a web of integrated transportation networks punctured by edifices of large-scale developments. These are fast becoming the identity of Kuala Lumpur. The way the city is developing could be understood in tandem with the intention of the government to position Kuala Lumpur as a global city (Kozlowski, Ujang, and Maulan 2017). This developmental model is driven largely by the property market, aided by an ongoing business-friendly political climate. These characteristics of Kuala Lumpur’s development – chiefly the way in which the relationship between private developers and the state is reworked in favour of a “growth first” development agenda – is consistent with the accepted indicators of neoliberal urbanization (Baeten 2018), a process which could be understood as the theory of neoliberalism put in practice. Seen in this light, Kuala Lumpur’s development could be understood as the formal manifestation of neoliberal urbanization. (U. Rossi 2019; Scott 2022; Brenner, Marcuse, and Mayer 2012).

Scholars have argued that “a neoliberal economy embedded in an authoritarian polity, as the de facto social regime in contemporary Malaysia” (Juego 2018) and that “there is a clear connection between the practice of governance and neoliberalism in the Malaysian planning system” (Marzukhi et al. 2017). These arguments establish the existing relationship between neoliberalism as a political ideology of governance, which in turn influences planning policy and the built environment. Meanwhile, the fast-track process of neoliberal urbanization has seriously impacted the identity, sense of place and the urban fabric of Kuala Lumpur (Kozlowski, Ujang, and Maulan 2017) while generating built forms which are disconnected from the local context (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022). The private property-driven development trend of Kuala Lumpur overlaps the global spread of neoliberalism as a developmental ideology and has given rise to what is understood as “new forms of spatial and social polarization” (Tedong, Grant, and Wan Abd Aziz 2015).

The ongoing process of neoliberal urbanization in Kuala Lumpur is manifested in large scale developments with characteristics of city within the city or urban islands. The accumulation of these various large scale urban islands led to a condition of archipelago urbanization in Kuala Lumpur. To understand this fragmented condition of urbanization, two theories on architecture and the city are worth revisiting: the Green Archipelago by O.M Ungers and Bigness by Rem Koolhaas.

Figure 1- Mid Valley City and KL Eco City, facing each other across the Klang River. Two examples of Kuala Lumpur’s city within a city or urban islands. (author’s photo)

2. Two Theories on the Archipelago and the Large Scale

2.1 O.M Ungers and the City Within the City, or the Idea of Archipelago

The idea of looking at the city as an “archipelago” could be traced back to the German architect and theorist Oswald Mathias Ungers in his manifesto City Within the City: Berlin as a Green Archipelago (1977). The manifesto was developed with a team of student collaborators made up of Rem Koolhaas, Peter Riemann, Hans Kollhoff and Artur Ovaska at a Cornell University summer programme in Berlin. This manifesto was an attempt to deal with the depopulation of Berlin and as an “antithesis to the current planning theory which stems from a definition of the city as a single whole” (Ungers et al. 1977). Instead, the project reimagines Berlin as a collection of “urban islands” each with different identity based on architectural form and the program contained within (Ungers et al. 1977). Ungers imagined these urban islands - selected based on their formal and historical significance within Berlin - becoming the points of further growth, while the area in between these islands is left undeveloped and will eventually revert to a green, natural state. In Ungers’s own words: “These islands-in-the-city would, in other words, be divided from each other by strips of green, thus defining the framework of the city in the city and thereby explaining the metaphor of the city as a green archipelago” (Ungers et al. 1977).

Figure 2- O.M Ungers, Berlin Archipelago, 1977 (UAA Ungers Archiv für Architkturwissenschaft, Köln.)

The fragmented nature of Berlin in the 1970s – yet to fully recover from the devastation of the Second World War – became the source of Ungers’s new idea of the city, which is not guided by an overall masterplan but “composed of islands, each of which was conceived as a formally distinct micro-city” (Aureli 2011) or “a system of fragments”(Lara Schrijver 2006). In Ungers’s vision, Berlin becomes “a city made of radically different parts juxtaposed in the same space” (Aureli 2011). These islands would serve as “pockets of meaning and significance” floating within the metropolitan landscape (Lara Schrijver 2006). In the Green Archipelago project, Ungers proposed the idea of a pluralistic – rather than uniform – idea of urbanization (Ungers et al. 1977). The islands of his archipelago city not just as points of formal density, but of collective spaces for people within the urban realm. As collaborator in the Green Archipelago project, Rem Koolhaas would absorb the ideas of Ungers and soon developed his own theory on architecture and the city: Bigness.

2.2 Rem Koolhaas and Bigness, or A New Kind of City

The theory of Bigness was put forth by Rem Koolhaas in his essay “Bigness or the problem of Large” from his book S,M,L,XL (1995), a monographic compilation of writings as well projects of his practice, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). Here, Koolhaas proposed that an architecture which has reached an extremely large scale becomes independent of the urban fabric and context (Koolhaas, 1995). Architecture is often thought of as the building blocks of traditional urban fabric or as the artefacts which reflect the gradual evolution of the city, referred to by Aldo Rossi as the “construction of the city over time” (A. Rossi 1982). When the scale of architecture becomes so large, however, it generates what Koolhaas sees as an architecture “which no longer needs the city” (Koolhaas, 1995). At the scale of Bigness, architecture breaks with the traditional idea of the city and through its scale and complexity alone it becomes itself a city, and coexists with the traditional city without connecting to it in any meaningful way . The lack of any contextual references means that this new architecture is free from tradition and could exploit the condition of tabula rasa, which resulted from the process of “creative destruction”, identified by Brenner and Theodore as a key component of neoliberal urbanization (Brenner and Theodore 2002). For Koolhaas, a very large building containing a variety of programs in unexpected combinations will generate unexpected encounters in line with his idea of “a new kind of city”. In his own words: “Bigness no longer needs the city: it competes with the city; it represents the city; it preempts the city; or better still, it is the city” (Koolhaas 1995). The architecture of Bigness breaks the traditionally complementary relationship between architecture and the city, becoming itself a city within the city, or an urban island.

Koolhaas’s theory on architecture and the city have been influential in the production of architecture since its publication, attracting both admiration and criticism. The programmatic mix promoted by Koolhaas in Bigness could be seen as an attempt to reclaim the idea of architecture as a social condenser, reclaiming the idea of the public and the collective within today’s capitalist cities (Cooreman 2005). On the other hand, critics have pointed out the influence of Bigness on the production and justification of large, iconic buildings, or “urban monstrosities” often detached from its context (Marcos 2009). The idea of the large buildings which simply ignore its surrounding context as argued by Koolhaas, have been criticised as an unethical position in the climate of the fractured process of contemporary urbanization and development (Marcos 2009). Bigness could be criticised as a theory which promotes large-scale developments, oblivious to the importance of the city as a public realm (Cooreman 2005; Otero-Pailos 2000). It could be argued that Bigness promotes and justifies the kind of large-scale, enclave developments now prevalent under neoliberal urbanization (Otero-Pailos 2000). Rem Koolhaas’s theory of Bigness could today be linked to the form of architecture and development under neoliberal urbanization.

3. Kuala Lumpur’s Archipelago Urbanization

3.1 From Colonial to Neoliberal: Kuala Lumpur’s Urban Development Revisited

Today, a drive around Kuala Lumpur reveals an urban landscape punctured by edifices of large-scale developments. Kuala Lumpur doesn’t appear to be a single city, but a collection of smaller cities such as Mid Valley City, KL Eco City, Empire City and so forth. There doesn’t appear to be a single centre but a collection of different centres such as Kuala Lumpur City Centre, KL Sentral and Bukit Bintang City Centre. Considering this phenomenon, it could be argued that Kuala Lumpur cannot be read as one coherent, uniform city but rather a fragmented city made of many “islands” of large-scale developments, which together generate a form of archipelago urbanization. The Green Archipelago was Ungers’s attempt at theorizing an emerging type of city based on the issues of urban fragmentation and depopulation facing Berlin in the 1970s (Ungers et al. 1977) . The idea of Kuala Lumpur as an archipelago city meanwhile is a description of an already existing phenomenon, not so much a theory but a retrospective reading of a condition which emerged under the influence of neoliberalism. How did this come to be?

Founded as a tin-mining settlement at the confluence of the Gombak and Klang Rivers in 1857, Kuala Lumpur’s growth has always been economically driven. The rivers were important means of transporting tin, while the early streets were meant to connect the river to tin mining fields (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022). In the early days, the bulk of the population was made up of Chinese migrants working in the mines, with their main settlement located in the area now known as Petaling Street. On the opposite bank of the Klang River were located the British administrators, who in 1884 founded the Selangor Club – now the Dataran Merdeka - as a social club for the colonial elites. The Malays, meanwhile, were a minority in the city until around 1900, when a piece of land north of the city was granted by the Sultan of Selangor as a permanent settlement for their community, now known as Kampung Baru. With the arrival of migrant workers from India in the beginning of the 20th century, the identity of Kuala Lumpur as an ethnically diverse, multicultural city was established (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022). The early urban fabric of Kuala Lumpur was made up of a tapestry of shophouses, kampung houses and colonial administrative buildings, some of which remain as landmarks today.

The growth of Kuala Lumpur from a colonial outpost to a major city was instigated by it becoming the capital of the newly independent Federation of Malaya in 1957. From the late 1950s onwards, significant portions of traditional urban fabric made up of a tapestry of shophouses and kampung houses were removed, to make way for a new development based on the architecture and urban ideas of modernism. The flurry of construction activity around the “Merdeka” or independence period led to the construction of national architecture icons such as the Bangunan Parlimen (Parliament Building), Stadium Merdeka (Merdeka Stadium), Stadium Negara (National Stadium), Masjid Negara (National Mosque), Muzium Negara (National Museum), Angkasapuri (National Broadcasting Center) and many more. These buildings, with their application of modernist principles adapted to local climatic conditions, represented the hopes and aspirations of a young, multicultural nation and became landmarks, not only for Kuala Lumpur, but the nation.

Further expansion of the city into a metropolitan region took place in the 1960s with the founding of the satellite cities of Shah Alam and Petaling Jaya, which were developed to encourage and accommodate the migration of Malay population from the rural to the urban areas (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022). The growth of the industrial sector as a result of the economic restructuring under the New Economic Policy further accelerated the process of Kuala Lumpur’s urbanization in the 1970s (Tedong, Grant, and Wan Abd Aziz 2015). Kuala Lumpur attained the status of a city in 1972, and the city council, Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur (DBKL) was established in 1974. During this period of development, the state retained control of the production of low-cost housing, to house the growing population of city dwellers, (Tedong, Grant, and Wan Abd Aziz 2015). Economic prosperity led to the growth of the city as a shopping destination as attested by the construction of air-conditioned shopping centres such as Ampang Park, Wisma Central, Sungei Wang Plaza and Bukit Bintang Plaza (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022). The growth of shopping also led to the interiorization of the urban experience, where air-conditioned shopping centres started to become more popular retail destinations, compared to traditional shop houses and markets.

Neoliberalism’s impact on the urban growth of Kuala Lumpur and its metropolitan region, first became apparent during the administration of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad (1981-2003) (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022). The Fifth Malaysia Plan (1985) which initiated practices such as privatization, free market policies and financial liberalization, helped Malaysia transition from a “state-dominated developmentalist approach towards a free-market model” (Tedong, Grant, and Wan Abd Aziz 2015). During this time, the state largely withdrew from its previous role in urban development, instead it focused on intervening through financial regulations to encourage profit-driven development by the private sector (Tedong, Grant, and Wan Abd Aziz 2015). From then on, Kuala Lumpur was shaped by the commercial drive of the developers.

3.2 Mega Projects: The Emergence of Kuala Lumpur’s Urban Islands

The 1990s saw the emergence of mega projects such as Kuala Lumpur City Centre (KLCC), Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) and the new administrative city of Putrajaya (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022). The development of KLCC, on a 100-acre site of the former Selangor Turf Club, was intended to be a city within a city. The development, consisting of the world-renowned Petronas Towers, corporate towers, a shopping mall, a convention centre, hotels and luxury apartments, composed around a 50-acre park, symbolized the ascendancy of commercial forces in shaping the city. The scale of the development presents a clear break from the surrounding urban fabric, establishing KLCC as a unique zone on its own. KLCC was the first of Kuala Lumpur’s cities within a city, an island in the urban archipelago.

Figure 3 - Kuala Lumpur City Center (KLCC). Development centered around a large, publicly accessible park. (Google earth and photo by Xiao Liu)

How do we recognize a development as a city within a city or an urban island? If we revisit Unger’s project for the Green Archipelago of Berlin, we can see how the city within a city is defined as a building or a group of buildings which are large in scale and distinct in architectural form, and program, embodying a strong and clear identity (Ungers et al. 1977). If we take KLCC as an example, it could be added that these islands act as focal points or attractors within a fragmented and disconnected urban landscape. Usually known as a “mixed development” they contain a multitude of different programs or development components which are largely commercial. A typical list of programs for one of these cities within the city includes shopping malls, office towers, hotels, and luxury apartments. These are sometimes complemented by other programs such as convention centres, transportation hubs, entertainment centres and even indoor amusement parks. This mixture of unrelated programs can be related to Koolhaas’s belief in the unexpected combination of program as outline in his theory of Bigness (Koolhaas 1995). Most of these developments are connected to public transportation networks but are primarily accessed by car, necessitating large areas for parking. Architecturally, these developments usually take the shape of a massive podium – usually containing parking and a shopping mall – topped by towers containing offices, hotels and apartments. Using the above characteristics as a guide, we can begin to identify and describe a few more examples of large-scale developments in Kuala Lumpur which can be understood as cities within a city or urban islands.

Another mega project developed in Kuala Lumpur in the 1990s which embodies the characteristics of a city within a city is Mid Valley City. This is a large-scale commercial development anchored by Mid Valley Megamall and The Gardens Mall. Mid Valley Megamall is a six-storey mall with 4 million sqft of floor area, containing over 450 retail outlets and 11,000 carparks. It is integrated with a convention centre, two hotel towers and four blocks of signature offices. The Gardens Mall meanwhile is a premium six storey mall with over 200 retail outlets, integrated with two office towers, one hotel tower and one service apartment tower. Both malls are linked internally and via an overhead bridge spanning the plaza between them. The Mid Valley City project broke ground in 1992 with the construction of Mid Valley Megamall and was completed in 2007 with the opening of The Gardens Mall. Although connected to the public transportation network through the Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) Komuter line, the Mid Valley City demonstrates a clear break in scale and connectivity from its surrounding urban fabric, embodying the characteristics of Bigness, where it “is no longer part of any urban tissue” (Koolhaas 1995). Surrounded by an intricate maze of elevated concrete driveways which provides ingress and egress into the multi-level parking zones, Mid Valley City is a self-contained world, a city within a city.

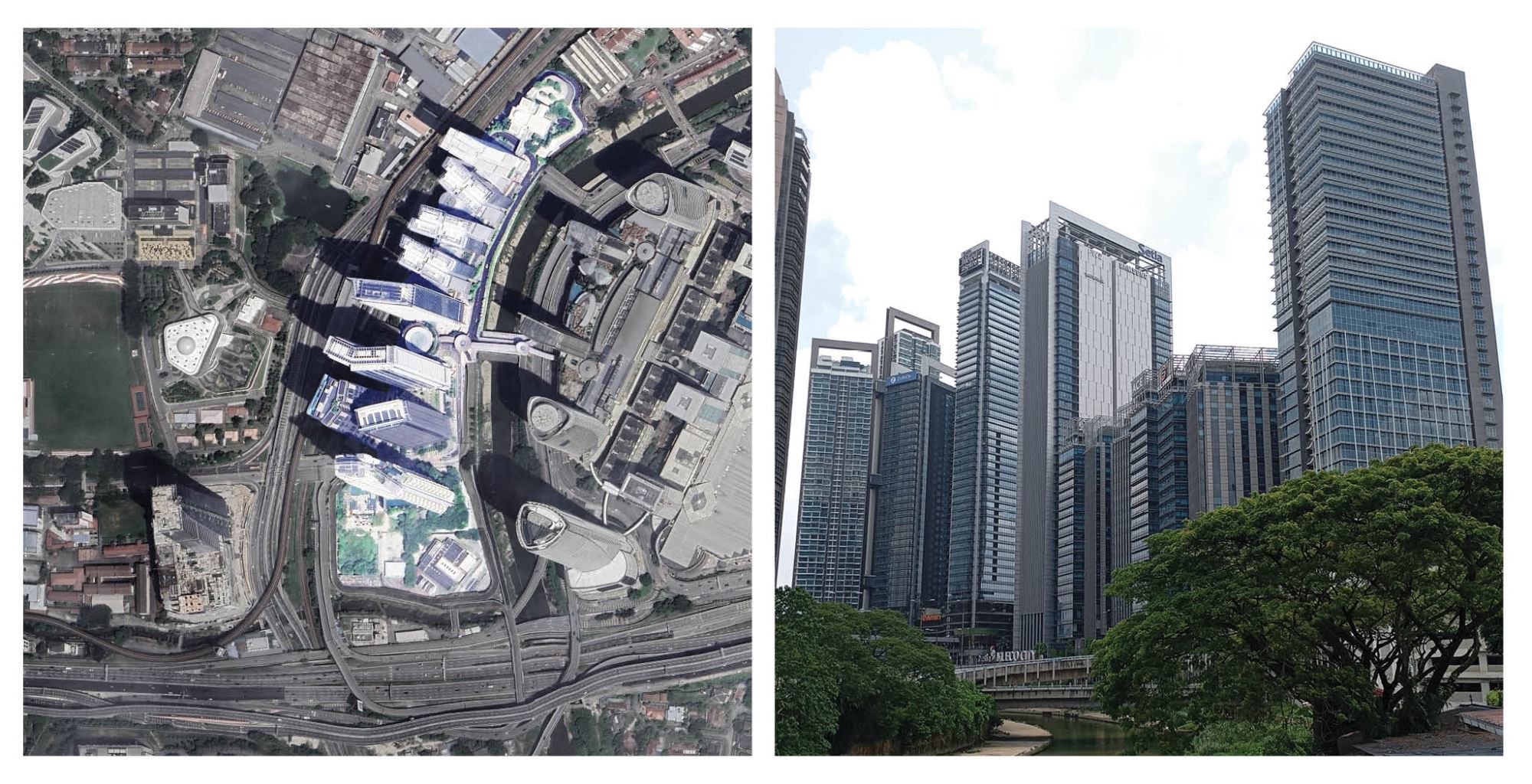

Figure 4 – Mid Valley City. Development anchored by Mid Valley Megamall (right) and The Gardens Mall (left). (Google earth and author’s photo)

The transport-oriented Kuala Lumpur Sentral (KL Sentral) also embodies the characteristics of an urban island. Developed on a 72-acre site in Brickfields, which was formerly the marshalling yard for KTM, KL Sentral is anchored by Stesen Sentral, the city’s main rail transport hub. The station integrates various transportation services such as Rapid KL, KTM Komuter, KTM Intercity, KLIA Express and KL Monorail. The masterplan of the site, by Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa, envisions the development as a city within a city, centred on the transport hub of Stesen Sentral. Work on the massive development began in 1994, with the station operational in 2001. The remaining development components, consisting of corporate towers, office suites, hotels, luxury apartments and a shopping mall were mostly completed by 2015. The scale and density of KL Sentral as well as the network of concrete driveways which surrounds it, disconnects it from the finer grain of the Brickfields neighbourhood which borders it. Furthermore, a significant portion of the development was built on a concrete plinth above the railway, elevating it above the street level of the neighbourhood. Meanwhile, the sleek language of corporate architecture which adorn the buildings offers striking contrast to the cultural vibrancy of Brickfields. Despite its connection to various rail networks, KL Sentral is still a somewhat detached island within Kuala Lumpur’s urban archipelago.

Figure 5 – KL Sentral. Development centered around a rail transport hub. (Google earth and author’s photo)

The development in Kuala Lumpur followed a similar pattern, throughout the 2000s, with the construction of more cities within the city. These included projects such as Berjaya Times Square, which houses an indoor amusement park and KL Eco City which is located adjacent to Mid Valley City on a site which formerly housed the Kampung Abdullah Hukum urban village. Other examples included Empire City, located on the edge between Kuala Lumpur and Petaling Jaya, and is surrounded by the most complex web of elevated driveways in the city. More recent examples include the Tun Razak Exchange (TRX), planned as a new financial hub around the upmarket Exchange TRX mall and Bukit Bintang City Centre (BBCC), built on the site of the former Pudu Jail, Kuala Lumpur’s colonial era prison complex. All these projects embody the characteristics of formal isolation and extremely large scale as described in the theories of Ungers and Koolhaas (Ungers et al. 1977; Koolhaas 1995). Based on the observations of these projects, it is possible to note the common traits of these cities within the city, which are as follows:

· Extremely large scale in relation to its immediate context.

· Disconnected and isolated from the rest of the urban fabric.

· Architectural emphasis on spectacular or novel characteristics: iconic towers, indoor theme park, ice-skating rink, roof gardens etc.

· Commercially driven programs: shopping malls, offices, hotels, luxury apartments etc.

· Heavily dependent on vehicular traffic despite the presence of public transport.

Historically, Kuala Lumpur has always been a city understood through elements of urban legibility such as public spaces and historical landmarks. Today, Kuala Lumpur is fast becoming a sprawling urban landscape dominated by the presence of various cities within the city. The accumulation of these large-scale developments - urban islands which dominate their surroundings - led to the fragmented characteristic of Kuala Lumpur’s urbanization. Kuala Lumpur is an archipelago city. Here however, the comparison with Ungers’s conception of the archipelago city ends. Ungers had imagined the islands within the archipelago city as spaces containing the elements of public space for the collective (Lara Schrijver 2006). Kuala Lumpur’s archipelago city meanwhile is a neoliberal edifice; driven by continuous growth and commercial development. They are signposts of a market-driven process of neoliberal urbanization and are spatial factors in the shaping of the public into passive “citizen-consumers” (Spencer 2016). Kuala Lumpur’s fragmented urbanization could be understood as a version of Rem Koolhaas’s “a new kind of city”(Koolhaas 1995). But what are the impacts of these kind of developments on the physical and social fabric of the city?

Figure 6 – Empire City. Note the complex web of elevated driveways surrounding it (Google earth and author’s photo)

3.3 Enclave and Exclusion: Issues Concerning the Large-Scale

The theoretical ideas put forth in O.M Ungers’s City Within the City: Berlin as a Green Archipelago and in Rem Koolhaas’s “Bigness” argued for the development of urban islands or large-scale architecture which are detached from the rest of the city fabric. For Ungers, the idea of the urban islands is in response to the depopulation of Berlin, while Koolhaas seeks the freedom from the traditional city through his argument for an architecture detached from the immediate context (Ungers et al. 1977; Koolhaas 1995). However, more recent studies by scholars have highlighted various problems concerning these kinds of developments. In a landmark study from the early 2000s, Erik Swyngedouw noted how large-scale developments have become one of the most common strategies for urban growth and competitiveness. The recent years have seen unparalleled urban growth through the implementation of large-scale projects, globally (Eizenberg 2019). Swnygedouw and others have argued that these large-scale developments are often enabled by “exceptionality measures” which work around existing planning measures and involve other measures such as state intervention and deregulation (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez 2002). This method of undertaking development projects is a sign of the neoliberalization of urban governance, with a shift in focus from investments in welfare or public projects in favour of projects which will benefit the private sector (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez 2002). Large-scale projects rarely provide solutions for actual urban issues and problems affecting the many, rather they are focused on providing assets for those with the means to accumulate (Eizenberg 2019). This leads to what have been observed as: “new planning cultures, new private-public relations, new urban demographic transformations and novel environmental concerns” (Eizenberg 2019).

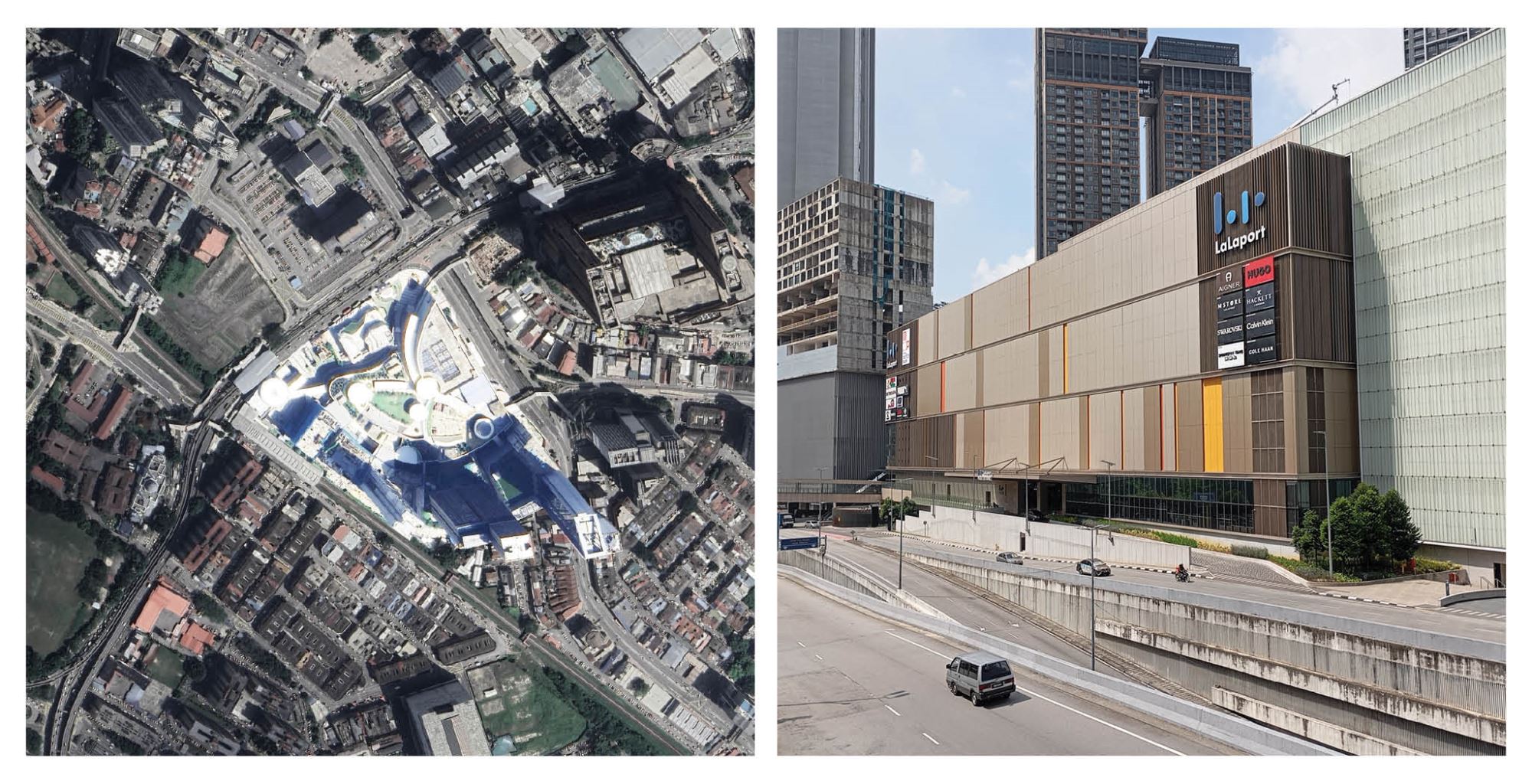

Figure 7 – KL Eco City. A linear city of towers, built on a site which formerly housed the Kampung Abdullah Hukum urban village (Google earth and author’s photo)

Physically, large-scale developments are instrumental in shaping the image of the city (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez 2002). The boldness and supposedly novel elements of these developments are often used to market an image of progress and new ways of living (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez 2002; Majerowitz and Allweil 2019). However, despite the surface appearance of progress, the outcome of the proliferation of large-scale developments are urban islands with enclave and exclusionary characteristics (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez 2002). According to Swyngedouw and others, these large-scale developments are: “often self-contained, isolated, and disconnected from the general dynamics of the city” (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez 2002). The outcome of this process is the further fragmentation of the urban fabric which brings with it problems such socio-spatial disparity (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, and Rodriguez 2002), uneven spatial development (Peck, Brenner, and Theodore 2018), polarization of the city through “new real-estate dynamics” (Baeten 2018), unequal cities and inequality of access to housing (Chen and Shin 2019a), rapid uncontrolled urban expansion characterised by exclusive urban enclaves (Kozlowski, Huston, and Mohd Yusof 2022) as well as social exclusion and inequality, spatial fragmentation, and environmental deterioration (Su 2023).

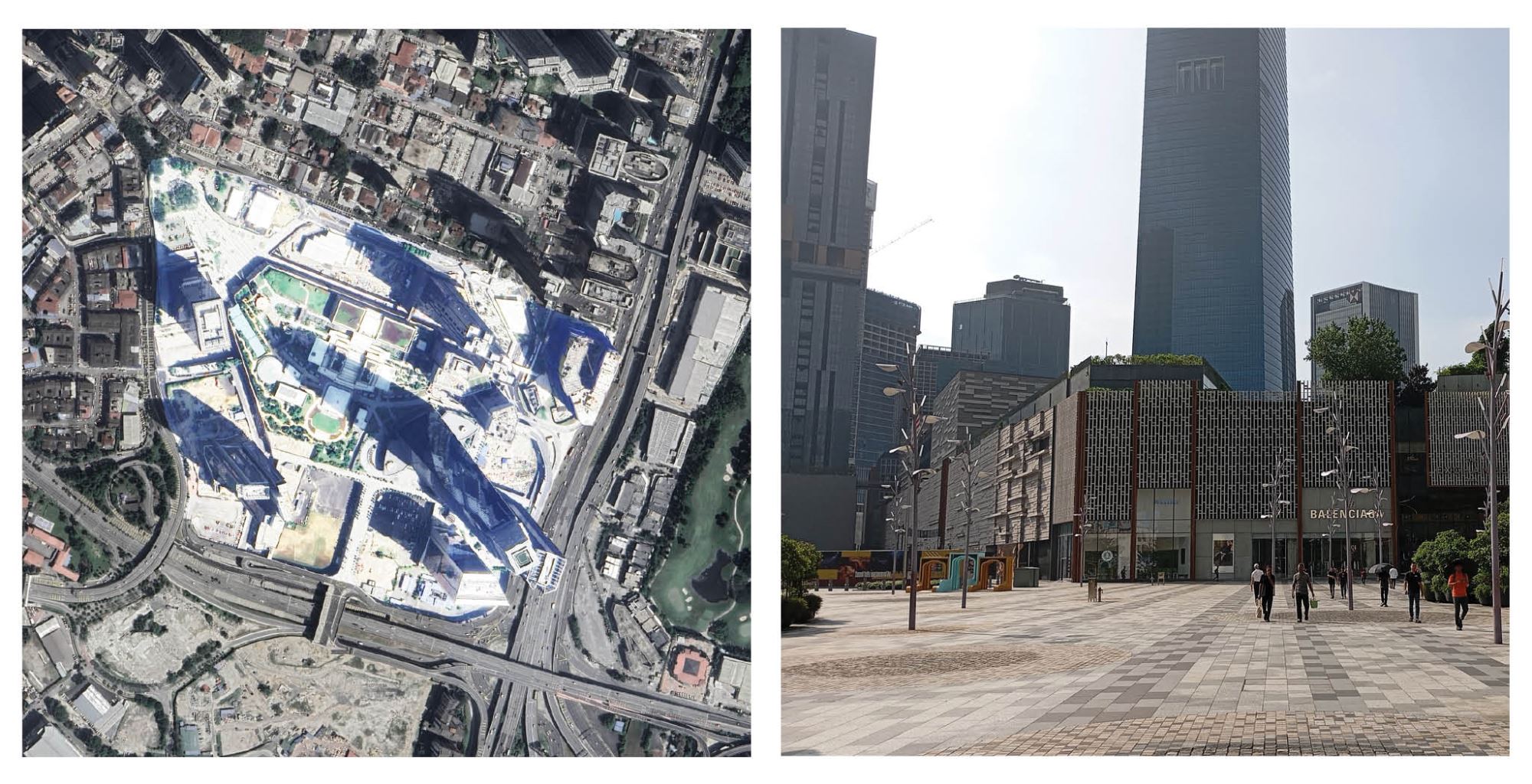

Figure 8 – Bukit Bintang City Centre (BBCC), built on the site of the former Pudu Jail, Kuala Lumpur’s colonial era prison complex. (Google earth and author’s photo)

Figure 9 – Tun Razak Exchange (TRX). An extensive urban plaza attempts to mitigates its relationship to the scale of the surrounding neighborhood. (Google earth and author’s photo)

4. Conclusion: The Archipelago City and Its Discontents

The entrenchment of neoliberalism as an economic ideology in Malaysia could be traced to the first administration of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed (1981 – 2003) who instituted practices such as privatization, free market policies and financial liberalization. From the Fifth Malaysia Plan (1985) onwards, the state largely withdrew from its previous role in urban development, encouraging profit-driven development by the private sector. These profit-driven development led to the mushrooming of mega projects in the form of isolated cities within the city or urban islands within Kuala Lumpur. Theoretical studies by O.M Ungers and Rem Koolhaas had anticipated the emergence of this kind of detached, large-scale developments. In Kuala Lumpur, these cities within the city could be identified by the following characteristics; extremely large scale in relation to its immediate context, disconnected and isolated from the rest of the urban fabric, architectural emphasis on spectacular or novel characteristics, commercially driven programs and heavily dependent on vehicular traffic. Various studies from around the world demonstrated how these types of development led to the fragmented nature of the urban landscape and socio-spatial problems. In the case of Kuala Lumpur, this topic would benefit from further research on identifying other developments which fits the criteria of city within a city, how these developments are shaping the fabric of the city and behaviour of city dwellers, and on possible architectural strategies (such as the integration of publicly accessible parks or open spaces) which could better connect them to the urban fabric and public life in the city. Beyond the physical aspects, this research could potentially be expanded to investigate the socio-political impacts of large-scale urban developments.

Figure 10 – Some of Kuala Lumpur’s cities within the city / urban islands, seen together. (by the author)

Today Kuala Lumpur is dominated by urban islands of high-density developments, which are commercially driven and isolated from the urban fabric. The proliferation of large-scale developments, turning Kuala Lumpur into an archipelago city reinforces fragmentation of the urban landscape and society. Rather than a city guided by history and public voices, Kuala Lumpur is becoming a playground of speculative commercial development. If in the past the identity of the city is defined by public spaces, historical buildings and buildings which are national landmarks embodying our collective memory, today it is driven by the profit-driven motives of developers and the drive for continual growth. This new identity of the city is manifested through the presence of multiple cities within the city, the urban islands which are the hallmarks of Kuala Lumpur as a neoliberal archipelago city.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the invaluable contribution of Alia Ahamad in the structuring of this article.

loading......

loading......