Author

Eleena JAMIL, Principal, Eleena Jamil Architect, B-03-08 Tamarind Square, 6300 Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia, eleena@ej-architect.com

Eleena Jamil is a Malaysian architect born in Penang. She graduated from the Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University, in the UK. She joined the Cardiff architecture faculty as a teaching assistant while completing her MPhil and PhD postgraduate research. Her PhD thesis, titled Rethinking Modernism: The Sugden House and the Mother’s House, examined the idea of “ordinariness” and “vernacular imagery” as an alternative to the reductive limitations of modern architecture. Eleena set up her eponymous architectural practice in Kuala Lumpur in 2005 and focuses on developing buildings within the context of Malaysia and Southeast Asia. She was shortlisted for Dezeen Architect of the Year 2018 and featured in 100 Women: Architects in Practice, published by RIBA in 2023. She has lectured widely and was recently appointed Adjunct Professors at the National University of Malaysia (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia) and Taylor’s University Malaysia. (142 words)

Abstract

The relationship between a building and the place in which it is set is one of the key determinants of its cultural and social value. The faltering of this relationship due to international industrialization leads to the re-assessment of local architecture and its response to the essence of place. This article explores how expanding the role of architects to include active involvement in the making processes of architecture can encourage a continuity of form and space shaped by local climate, tradition, and material culture. It looks at how Eleena Jamil Architect, an architectural studio based in Malaysia, responds to place in small projects that it initiates and builds collaboratively with small teams of craftspeople, builders, students, and their teachers. The article begins with a literature review and the observation of scholars on the relationship between buildings, place, and typologies, as well as the significance of shaping built environments to the natural environments in the increasingly urgent issue of our planet’s climate. It then proposes ‘making’ as an essential part of architectural practice, where ideas, contextualism and sustainable approaches could continue to develop in close interaction and association with the actual physical construction at the site. In the final part, five pavilion projects primarily produced by the studio are studied in terms of their responses to place in terms of their forms, techniques, and materiality.

Keywords

Critical Regionalism, Contextual Architecture, Role Of Architects, Co-Creation, Tradition, Culture

Introduction

Architecture is fundamentally a cultural and social enterprise. The relationship between a building and the place in which it is set is one of the key determinants of its cultural and social value. Things began to change in the 20th century as a result of international industrialization. In particular, the historic method of using a building's material and form to respond to place and climate was replaced by highly processed building materials and mechanical systems of heating, cooling, ventilation, and lighting. This development frequently manifested in a style of grids applied to large-scale urbanization and tall buildings with their sealed envelope and air-conditioning systems, dominating the skyline of major cities around the globe.

The alarming rise in global temperatures and prevalent extreme weather conditions raise serious concerns about how we should develop our cities. Reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions in building operations is no longer sufficient to reduce the prevailing problems brought on by climate change. Serious considerations must be given to pre- construction processes, such as the materials we build with, where and how they are sourced, and the amount of energy required to transform them from their original state to one that can be used in construction. It is also essential to evaluate critically whether building anew is necessary in the first place.

This article explores how Eleena Jamil Architect, an architectural studio based in Malaysia, responds to place in small pavilion projects that it initiates and builds collaboratively with small teams of craftspeople, builders, students and their teachers. The article begins with a literature review and the observation of scholars on the relationship between buildings, place, and typologies, as well as the significance of shaping built environments in response to the natural environment in the increasingly urgent issue of our planet’s climate. It then proposes ‘making’ to become an essential part of architectural practice, where ideas, contextualism and sustainable approaches could continue to develop in close interaction and association with the actual physical construction at the site. In the final part, five pavilion projects primarily produced by the studio are examined in terms of their responses to place in terms of their forms, techniques, and materiality.

Responding to Essence of Place

With buildings now part of the problem, seeking solutions that work with a place rather than against it is crucial. How can architecture truly ground itself to place? Anglo-American critic and historian Kenneth Frampton offered an alternative to the threat of universalisation he witnessed with his 1983 Perspecta article titled Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance1. For him, grounded architecture could develop within the specific conditions of a local context: an approach in which climate, context and tectonics are so embedded in local material conditions and cultures as to resist universalisation and homogeneity. He cited the work of architects such as Jørn Utzon’s Bagsvaerd Church in Copenhagen of 1976 as containing complex meaning that achieves a “self-conscious synthesis between universal civilisation and world culture,” and Alvar Aalto’s Saynatsalo Town Hall of 1952 for its ‘tactile sensitivity’ to its context which complements the sensory experience.

In his book The Environmental Tradition: Studies in the Architecture of Environment2, academic and architect Dean Hawkes expressed a parallel sentiment when he wrote about designing for the climate rather than against it with a historical perspective, which can indicate how to address new environmental priorities. He also wrote about the importance of typologies in contemporary design. He describes typologies as containing within them the logic of form, and responses connected with reason and use, which create deep bonds with place and climate and allow us to start from a position of knowledge rather than from the beginning. From here, we can review solutions from the past and begin to analyse, dissect and improve designs based on contemporary concerns. He elucidated that “… the great value of typology, as opposed to singular types, in the production of new designs is that it constitutes a store of alternatives from which the starting point for the development of a promising solution might be drawn.”3

In a keynote lecture presented at the 12th International Docomomo Conference in Espoo, Finland, in August 2012, renowned Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa, spoke of the importance of buildings being rooted in the historicity of their place, and of contributing to a sense of cultural continuum:

“The first responsibility of the architect is always to the inherited landscape or urban setting; a profound building has to enhance its wider context and give it new meanings and aesthetic qualities. Responsible architecture improves the landscape of its location and gives its lesser architectural neighbours new qualities instead of degrading them. It always enters a dialogue with existent conditions; profound buildings are not self-centred monologues.”4

Frampton, Hawkes, and Pallasmaa propositioned several ways of creating meaningful architecture in response to place. For them, continuity is necessary for consistency and strength of architecture, but this does not mean an absolute commitment to past culture, tradition, and values. Avoiding and limiting creativity and innovation as a form of respect for tradition disregards the primary purpose of architecture, that is, to create lively and dynamic built environments responsive to new human needs.

Place-responsive contemporary architecture carries with it the identity of its community, distinguishing a place from another. It contains the message, concept, and characteristics attributed to the place where it was conceived. Therefore, it depends on the geography, traditions, insights, and knowledge of the community and its history. It can show all these dependencies while reacting to technology and society's transformative and continuous development.

About Making

The origins of the architecture profession lie in the craft of making. Before it was considered a profession, architecture was practiced in close association with a building’s physical construction on-site. For example, in Southeast Asia, the making of a traditional Malay house was carried out without drawings and was considered a manual occupation. A sophisticated form of rural domestic architecture, the Malay house consisted of modular rectangular volumes raised on stilts and was built by the traditional tukang or craftsperson, who acted as both architect and maker, assisted by a team of apprentices and local community members. Practising a highly ordered building process that reflected a set of rituals and local beliefs, and using anthropometric proportions, the tukang was well-versed in the interlocking timber- jointing technique known as tanggam5. They would also have had a deep knowledge of the local environment and natural building materials, including timber, rattan and thatch, and known where and how to source them. In addition to these skills, they were a master carver who produced intricate ornamental carvings and understood their aesthetic principles and meanings.

Figure 1: The Malay House

Figure 2: Tanggam detail in a Malay House

For the tukang, ideas, forms and their execution were perceived as a single organic process. Like many other craftspeople, they picked up their craft through rigorous apprenticeship, often from a very young age, gradually developing manual dexterity and an intuitive sense of tools, materials, structure, proportion and aesthetics, until they became a holistic building expert. In contrast, the practice of modern architecture is a three-fold process: analysing, imagining, and making. An architect analyses by collecting, documenting and mapping information, and then reflecting on and synthesising it. Following this, the results are translated into imagined forms and spaces using sketching, drawing, and model-making. Juhani Pallasmaa described the process as follows:

“While drawing, a mature designer and architect is not focused on the lines of the drawing, as he is envisioning the object itself, and in his mind holding the object in his hand and occupying the space being designed. During the design process, the architect occupies the very structure that the lines of the drawing represent … The architect moves about freely in the imagined structure, however large and complex it may be, as if walking in a building and touching all its surfaces and sensing their materiality and texture.”6

This idea of architectural thinking and exploration through making can be extended beyond the ‘three-fold process’ to on-site construction and its processes. The connection to activities at the site can reinforce the connection between architectural practice and the realities of making – between idea and matter, form and its execution7. This approach is akin to that of the craftsman, where craftsmanship arises from manual skill training and experience in the actual making processes. In his book The Craftsman, the cultural historian Richard Sennet narrates this when he wrote, “Every good craftsman conducts a dialogue between concrete practices and thinking, his dialogue evolves into sustaining habits, and these habits establish a rhythm between problem solving and problem finding.” 8

In 2014, the architecture studio was invited to exhibit some of their bamboo projects at Palazzo Bembo in Venice, as part of a concurrent programme of the 14th Architecture Biennale. They displayed miniature bamboo models and life-sized mock-ups supported by detailed drawings and images, all of which told a story about making. Built with satay sticks, the models were used to examine specific aspects of our architectural projects, such as structural composition and tectonics and how they affect the overall concept of a building, while also helping to externalise ideas and put them into practice on a diminutive scale.

Not far from the little exhibit, at the Arsenale, was the Indonesian national exhibition, Ketukangan: Kesadaran Material, meaning ‘Craftsmanship: Material Consciousness'. Against the persistent sound of building tools in use, the making of structures was explored through six common materials: timber, bamboo, brick, stone, concrete, and steel. Using text, moving images, and sound, the exhibition revealed how the craftsmanship and labour involved in handling each material has become an influence in developing the nation’s architecture. These were found to have strong affinities with the studio’s bamboo display, where making was exposed as an instinctive way of working with materials that are cultivated, produced, selected and applied by local people in their own environment, using tools and techniques they have developed.

The process of thinking and exploring ideas through making is not explicitly expressed the studio’s practice of architecture, but it remains an essential aspect of its daily architectural activity. In 2021, during the Covid pandemic, the lull of this period permitted the opportunity to think more deeply about making, craftsmanship and the architect's role. With a grant called ‘Connections through Culture’, provided by the British Council, the studio embarked on a project that explores making and the craft of building in relation to material culture, building processes and engagement with local communities9.

Figure 3: A tukang working on timber house railing in a Malay House

The project began by recording conversations with three Malaysian tukangs, who are still practising the traditional method of building timber houses, to develop an understanding of their role, process and worldview. From this point of departure, ‘making’ was explored in the work of contemporary architects and designers in the broader region of Southeast Asia, and in Britain. We spoke to Patcharada Inplang and Varudh Varavarn in Thailand, and Andy Rahman, Florian Heinzelmann and Daliana Suryawinata in Indonesia, while in the UK we consulted Rodrigo Garcia Gonzalez, Amin Taha and members of the 121 Collective.3 There is an underlying commonality in the work of these practitioners, where each seeks to reference their distinctive culture, tradition, building method and climate through sustainable practices.10

A few common threads emerged from these conversations: a conscious effort to explore and experiment with local and sustainable materials and building techniques, to be highly involved in the making processes and to collaborate with local craftspeople to reach a deeper understanding of how to use them. These attitudes, and the work they produce, illustrate that working with what is at hand does not necessarily mean going back to pre-industrial ways, but, rather, opens up new possibilities for a post-industrial age while keeping local material culture and vernacular traditions dynamic.

This close connection with making was the default in architecture until the modern era’s transition to specialization and separation of design from the building process. Today, architects work in isolation away from the construction site, in their studio, with employees producing drawings and specifications instead of being directly immersed in the materials and process of making. Moreover, architectural education, with its growing emphasis on intellectualism and theoretical thinking, has created an additional distance between the studio and the construction site, further diluting the principles of craft in the architect's work.

The process of architectural design has also changed considerably with technology. It is now possible to design a complete building in a matter of weeks using computer modelling software, without having to consider how building components are made, who made them or where they originated. Built into this software are standard building element catalogues, which enable three-dimensional walls, doors, windows, roofs, gutters, etc, to be added quickly to a building. Visualisations are accessible at the click of a button, with extraordinarily little room left to the imagination. When turning designs into physical buildings, this way of working has a trickle- down effect, encouraging the quick assembly of generic components, often high in embodied energy and made from materials extracted or produced in far-off places, to simplify the construction process.

Process of Making in Practice

Construction methods in Malaysia and, indeed, Southeast Asia primarily revolve around the same techniques: a structure of columns and beams made of reinforced concrete, infill walls made with concrete masonry blocks, and floors of concrete. This method of construction is extensive due to its low cost and easy execution at site by low-skilled workers. Concrete is responsible for around eight per cent of all global carbon emissions, where most of its emissions are released in its process of production.

More sustainable and less ecologically damaging building techniques can be found in vernacular examples. Traditional Malay houses are built in direct response to climate that roots them in local construction techniques and natural material culture. They are made from thriving natural vegetation such as bamboo, timber and palm leaves. Their floors are raised on stilts to keep it dry, and a framed system holds up a steeply pitched roof with low overhangs to expel rainwater and protect the interior from direct sun. The house uses a clever modular system that permits future extensions and is put together using an interlocking jointing system known locally as tanggam, allowing the house to be dismantled and moved to a new location when required. This vernacular technique is seldom in practice today, threatened by the desire for concrete and masonry which have come to symbolise social status; timber, bamboo and woven leaves are often seen as the material of those who do not have the means to build with concrete – even though concrete is now widely available and increasingly affordable.

The opportunities to explore, experiment and innovate using local and sustainable materials and building techniques are few and far between. It is very rare to come across commissioning clients willing to fund the exploration of new techniques and natural materials such as timber and bamboo in their projects, often citing problematic issues associated with durability, complexity, and perception - bamboo, for example, being regarded as a poor man’s building material. Small pavilions mentioned in this article present opportunities to explore what large projects could not. Their small size and inevitable low costs permit the architectural studio to become more than a designer. In almost all pavilion projects undertaken, the studio initiates and builds by working collaboratively with small teams of craftspeople, builders, students and volunteers in a way that gives greater control over design and innovation, leading to the exploration of the potential of traditional methods and materials in contemporary forms. Besides working in the studio, team members spend considerable time at the construction material yards, workshops, and construction sites. There, they are directly involved in exploring materials and techniques with those who actively build the structures.

This approach includes a strong tendency to work with materials in their “as-found” state like they were in vernacular exemplars, which usually means as they are delivered, or in their early condition when first applied and before extra layers or coatings are added: unclad steel structures, bare concrete, clay bricks, wood and bamboo. Rather than imposing a preconceived idea or unnatural appearance on materials, we prefer to work to their unwritten rules, allowing each substance to fully express its individuality and physicality. Few of these materials are available in off-the-shelf prefabricated forms, and working with them is therefore based on the craftsperson’s knowledge and dexterity, stemming from their usage in vernacular architecture. The contemporary architectural and construction industries believe this way of working belongs to the past, as it adds time and complexity. The studio, on the other hand, finds it enriching and prefers to celebrate a relationship with the construction team that is collaborative rather than authoritative and that avoids directing or controlling their activities.

Figure 4: Eleena Jamil Architect, The Shadow Garden Pavilion, 2016

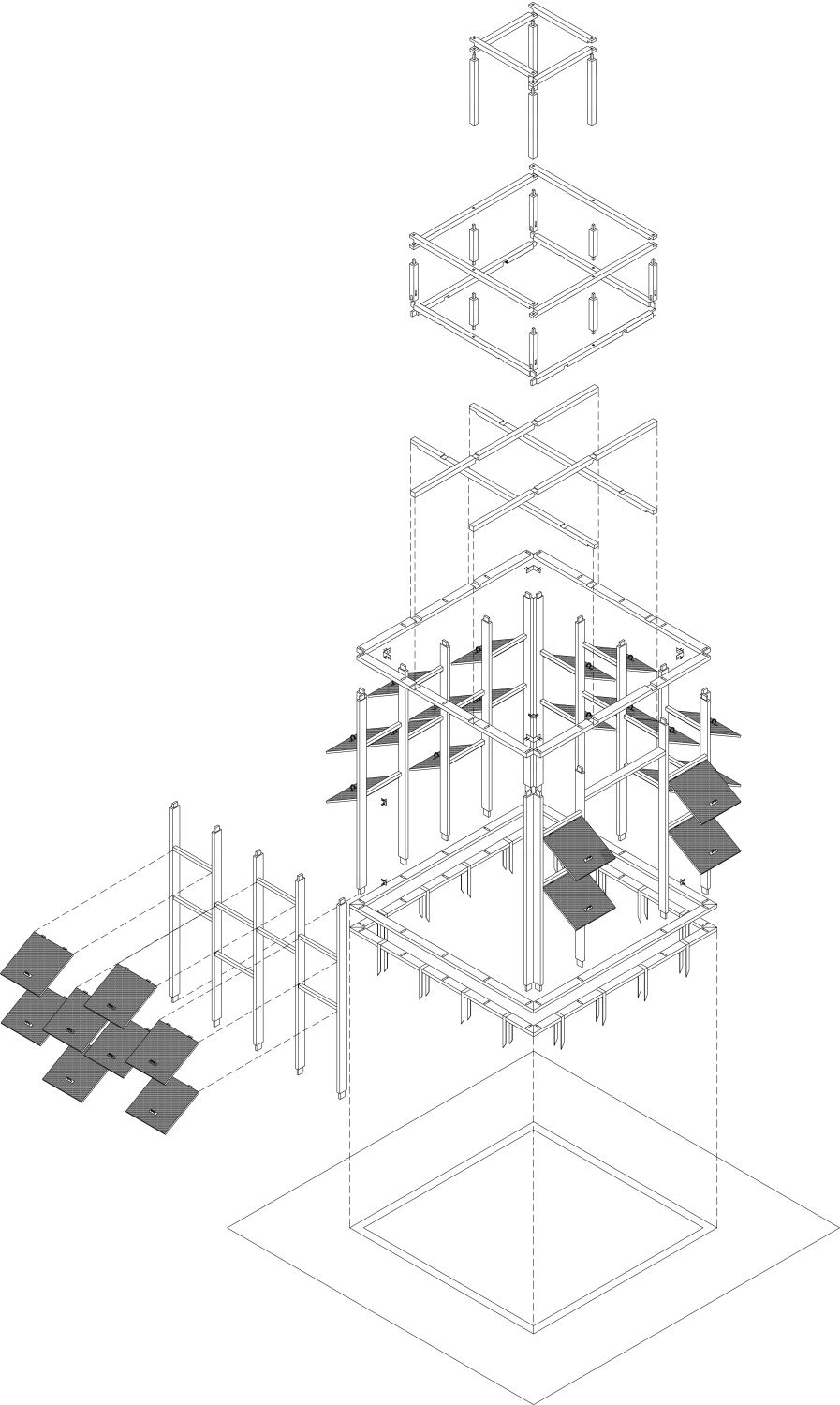

Figure 5: Eleena Jamil Architect, Detail axonometric of the Shadow Garden Pavilion, 2016

Figure 6: Eleena Jamil Architect, Students working on the Shadow Garden Pavilion, 2016

The traditional tanggam method used in Malay houses was adopted in the Shadow Garden Pavilion project, completed in 2016. The idea of growth, flexibility and impermanence is intrinsic to the timber architecture of this region, where sections cut from local Merbau wood are interlocked without the use of nails, screws or fasteners, to form a stable framed structure. A group of architecture students and lecturers from Taylor’s University volunteered to help with the building work, and together with the studio, developed a series of mortise and tenon, dovetail, and keyed joints to create a timber structure based on the tanggam method, so it could be quickly assembled and dismantled on-site. Drawings illustrate the joints in great detail so that students, after going through a two-day woodworking course at the university workshop, could cut timber sections to create an array of mortise and tenon, dovetail, and keyed joints based on the tanggam technique. Fabrication and assembly of the entire wooden structure took about three weeks to complete.

Figure 7: Eleena Jamil Architect, Meranti Pavilion, in the workshop in Selangor Malaysia, 2017

Figure 8: Eleena Jamil Architect, The making of Meranti Pavilion in the workshop in Selangor Malaysia, 2017

A similar concept was used for the Meranti Pavilion (2017). Here, the pavilion needed to be designed in a way that would enable it to be moved from a workshop in Malaysia, where it was fabricated, to an exhibition hall in Orlando, Florida, for about three weeks, after which it would be dismantled and stored until required again. By working in close collaboration with skilled local carpenters, a series of standardised, modular components made from local Meranti wood was designed and fabricated. At the same time, several mock-ups were produced to determine the shape, size and weight of a module that could be easily handled and packed tightly into a shipping crate. The use of a simple interlocking joint system permitted the modules to be assembled quickly to form a 4 x 4 metre rectangular enclosure in less than 24 hours, using basic tools such as power drills and screwdrivers, and, if necessary, to be reassembled in different configurations, much like Lego bricks.

Figure 9: Eleena Jamil Architect, WUF09 Pavilion, Kuala Lumpur, 2018

Figure 10: Eleena Jamil Architect, Volunteers working on the WUF09 Pavilion, Kuala Lumpur, 2018

Figure 11: Eleena Jamil Architect, Craft students working on IKN Pavilion, Kuala Lumpur, 2019

Similar to timber, bamboo is one of the oldest building resources but was never developed into a modern construction material. The interest in bamboo as building material led the studio to experiment with rings for the World Urban Forum 09 (WUF09) Pavilion, built in 2018 for an urban forum event organised by UN-Habitat in Kuala Lumpur. The different-sized and -shaped rings were cut from whole culms, cast off from another project, and packed tightly between vertical and horizontal bamboo frames to form wall claddings. Coloured panels were then meticulously inserted into the small circular openings, resulting in embellished screens rich with texture. Here, a very old building material, rarely used in modern construction, was therefore reimagined as part of a new making system. Similar interesting formations are seen in our IKN Pavilion, built in 2019, which was designed and constructed with craft students studying textile, metal, and wood crafts at a local craft institute. The students were asked to “adorn” a series of upright bamboo frames using their skills in innovative ways. Provided with bamboo, rattan, and hemp rope, in addition to a host of leftover craft materials teeming with hues and textures they found around their studios, they experimented with different techniques, such as weaving, plaiting and lashing. This collaborative and creative exchange generated interesting making methods that could be adapted to more complex applications.

Figure 12: Eleena Jamil Architect, Duduk-Duduk Pavilion, Kuala Lumpur, 2024

Figure 13: Eleena Jamil Architect, Students working on the Duduk-Duduk Pavilion at their university workshop, Kuala Lumpur, 2024

In the Duduk-Duduk Pavilion completed in 2024, bamboo was again explored, this time with timber in designing a small structure derived from traditional wakaf structures.Wakafs are small pavilions that act as public shelters made from local natural materials with raised floors and large overhanging roofs. The Duduk-Duduk is made from timber sections supported off the ground by a steel frame. The structure supports four wooden seats with angled back support. The roof is steeply pitched with a large overhang and is covered with flattened bamboo panels, locally known as pelupuh. The pelupuh, produced from local bamboo, was cut into uniform sizes with a tapered bottom edge to create individual shingles. These shingles, pigmented in three different vibrant colours, are then arranged on the roof battens in a random array of colours. This creates an interesting and lively roof covering that beautifully reflects the verdant park's greens and yellows. The pavilion was built in collaboration with students from the National University of Malaysia (UKM). Students worked under the architect's and university workshop tutors' supervision to fabricate the pavilion. Most of the work was carried out at the workshop, with a final 3-day assembly at the site. This collaborative process spanned about four weeks, with the students working on days that they did not have lectures to attend.

The active involvement in building activities means that design development does not end before construction begins, but continues alongside it and trickles into the making process. For example, in the Bamboo Playhouse project (2015), the studio team worked with skilled craftspeople versed in traditional bamboo jointing methods, using natural rope lashings to joint culms. Typically, rope lashings will decay and loosen over time, so a more durable solution was required. Working closely with the workers on-site as building work progressed, more efficient and durable jointing methods were created where lashings were combined with bolting and clamping. Prototypes and full-scale mock-ups were also made to convey exactly what was required. This exchange resulted in increased knowledge and safer, more resilient structures based on local materials.

Conclusion

The strategies described above can be considered part of a laissez-faire attitude that prevents a predetermined final state, and allows motivation and innovation to continue in tandem with the building process. Such an open-ended approach is easier to adopt in small-scale, self-built or self-managed projects, unlike more formal and highly controlled procedures such as a production line, where tasks are compartmentalised and conform to specific programmes. Though efficient, this more formal system depends on machine-fabricated and standardised building components. In contrast to this, the cultural continuity and environmental awareness embodied in a form of making that is rooted in local methods can offer valuable insights into reimagining modern building practices. The making process involved in our timber and bamboo pavilions shapes form and construction beyond the aesthetic dimension, and allows us to tap into the skills and knowledge of traditional makers. Working in such a manner enriches architecture and catalyses a more profound social and cultural engagement between architect, maker, building user and the public realm.

loading......

loading......