Author

Jia-Ping LEE, Director, Pollin8 Sdn Bhd & Start-up Board Member of Placemakingx, Email: jiaping@placemakingx.org

Jia-Ping is a director of Pollin8 Sdn Bhd, an urban rejuvenator and place brand strategy consultancy. As a result of her rejuvenation work on the Kuala Lumpur heritage core as Think City's Programme Director (semi government frm), she has now taken the lead in advocating human-centric place brands via placemaking, not only in Malaysia but also the South East Asian region. Jia-Ping has a Bachelor of Arts degree in Political Science from the University of Melbourne, Australia and guest lectures at University Malaya and University of Melbourne (School of Architecture). In 2019, she was the key note speaker at Convention in The D, organised by the Michigan Municipal League, Detroit Michigan.

Abstract

This article explores the concept of "Malaysian-ness" as an evolving and embodied identity expressed through the practice of placemaking. Rooted in Malaysia's rich multicultural heritage — shaped by centuries of trade, migration, and cultural fusion—the essay highlights how early diasporic communities were the country's original placemakers, crafting spaces that refected a deep sense of belonging, diversity, and community. Contemporary placemaking in Malaysia builds on this legacy by emphasizing context, cultural relevance, and community engagement. Case studies from George Town, Ipoh and Kuala Lumpur demonstrate how place-led development can foster cultural preservation, creative economies, and inclusive public spaces. Through historical insights and modern examples, the article underscores placemaking as a tool for sustaining Malaysian identity, encouraging community cohesion, and celebrating the country's dynamic cultural tapestry.

Experiencing Malaysian-ness: The Embodiment of Identity in Placemaking

The concept of Malaysian-ness conjures a vibrant mosaic of images, words, and a symphony of sounds in my mind. What makes Malaysia extraordinary is its intricate tapestry of ethnicities and cultures—a richness we embodied long before "diversity" and "inclusion" became global buzzwords.

Our multicultural roots trace back centuries, from the 15th-century prominence of Malacca under Parameswara1 to the 18th-century establishment of Penang and Singapore as free ports by the British East India Company. Over time, the port cities welcomed traders and settlers from across the globe—India (Tamils, Punjabis, Malayalees, Telugus), China (Hakkas, Cantonese, Hokkiens, Hainanese, Fuchows), Armenia, the Baghdadi Jewish community, Portugal, England, the Netherlands, and beyond.

This fusion of peoples, interwoven with local traditions, blossomed into a profound cultural heritage—both tangible and intangible—shaping everything from architecture to the very fabric of our social life.

This cultural diversity infused our social life with depth, energy, and an irresistible allure. If placemaking is the art of creating spaces that foster community, identity, and belonging, then I believe the early diasporic communities were the nation's original placemakers—crafting vibrant spaces that still captivate us today. Their legacy lives on, most tangibly in the UNESCO World Heritage cities of Malacca and Penang, where their contributions continue to be celebrated and enjoyed.

From the bustling kopitiams (cofeeshops) where languages and favors blend efortlessly, to the harmonious coexistence of temples, mosques, and colonial shophouses, our places tell a story of adaptation and unity. The vibrant pasar malam (night markets), the rhythmic calls to prayer mingling with temple bells, and the ornate craftsmanship of Peranakan2tiles all contribute to an environment that feels distinctly Malaysian—warm, layered, and alive.

The early traders, settlers, and local communities were our frst placemakers, creating nodes of exchange that evolved into thriving cultural hubs. Today, this legacy lives on, where every street corner whispers tales of convergence. But Malaysian-ness isn't confned to heritage zones; it thrives in modern spaces that embrace rojak creativity—mamak stalls under skyscrapers, contemporary art infused with batik motifs, and public squares where festivals of every ethnicity unfold.

Malaysian-ness, therefore, is not a monolithic concept but a dynamic interplay of traditions, values, and aesthetics. Contemporary places and placemaking in Malaysia seek to capture this diversity while fostering a sense of community, unity, shared identity and belonging.

Tun Perak Fountain

Tun Perak Pocket Park by DBKL and Think City

Placemaking in Malaysia

Contemporary placemaking in Malaysia goes beyond aesthetics; it is about creating places that tell stories, evoke emotions, and foster connections, all set in a specifc location. Placemaking is about the creation of a place that is relevant to the community that resides and works there. Hence the term Malaysian-ness is not easily defned and difers from place to place depending on the existing communities. Cities in Penang are vastly diferent in character from those in Kuala Lumpur, Penang and Ipoh. Each has their own uniqueness which, when captured, distilled and bottled correctly and with care, will result in a place that not only attracts visitors but also talent. This is very important in smaller towns where many are losing their talent to bigger cities and more developed countries.

The idea of contemporary Placemaking was introduced by two alternative thinkers—William H Whyte3 , and Fred Kent of Project for Public Spaces4 (PPS) in the 70s. Through his keen observation of social behaviour in public spaces, Whyte, an urbanist, sociologist, organizational analyst, journalist and people-watcher, concluded that—What attracts people most, it would appear, is other people5. Through the reimagining of Bryant Park with Fred Kent of PPS in the 1980s, the practice of placemaking took of with Kent declaring—If you plan cities for cars and trafc, you get cars and trafc, if you plan for people and places, you get people and places.

In Malaysia, one of the frst developers to practice placemaking (before the term was made popular) was Sunrise and the development of the Mont Kiara precinct which was previously a rubber estate. This high density area introduced the practice of community development by introducing art spaces within their condominium grounds. These spaces together with micro retail, were run by artists and small businesses, became popular with both the expatriate and local communities. Together with great education and social infrastructure, Mont Kiara quickly became a sought-after address in Kuala Lumpur.

In the 2010s, placemaking gained attraction within two large organisations namely Think City (a semi-government urban Think and Do tank) and Gamuda Land. It was at this juncture that the term placemaking started to penetrate the market. Think City was infuenced by Fred Kent of PPS and Gamuda Land, who created a placemaking department then led by Mardiana Rahayu Tukiran who supported Think City's advocacy of placemaking. Both understood that for placemaking to succeed, context was everything. The placemakers in Think City were trained by PPS and they started to put into practice some of their methodologies in rejuvenating parts of George Town. But before we delve deeper into Think City, we must frst rewind the clock back to 2008 when both Malacca and George Town were jointly awarded UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

George Town Penang — A Place Led Case Study

In 2008 Khazanah (the sovereign wealth fund of Malaysia) commissioned a masterplan titled The George Town Transformation Programme (GTTP). GTTP called for a Penang-centric approach that sought to restore the city to its former glory from a Penang perspective as opposed to a homogenous western aesthetic approach. So what were the key elements of this Penang-ness? One of the main aspects was the imperative to ensure that the local community was, as much as possible, not be displaced by any future rejuvenation and that the “Place” that they were familiar with would still exist and not be wiped out by modern transformation.

One such example was the existence of street vendors—it was unanimously agreed by the Malaysians in the GTTP team (myself included) that these street vendors be allowed to continue their operations as much as possible, as they were as vital to the place's identity as the historic buildings. Any move to relocate them into a covered hawker centre would not be considered. The guidelines, set out by UNESCO were also another aspect of cultural and social preservation that has kept the core historic zone of George Town pretty much intact.

Another great placemaking success in George Town, located in the bufer zone is Hin Bus Station. Previously one of the city's most stylish private stations, it was shuttered in 1999. An early adopter of placemaking, Hin Bus Station led by Tan Shih Thoe, has successfully built a great place for the craft and artisanal community and to become a must-visit place. This fourishing started with a then little known fgure Ernest Zacharevic who decided the place was ideal for an exhibition title—Art Is Rubbish is Art.

Zacharevic who has since become an icon is credited with the revival of George Town through his charming wall murals throughout the core zone. The success of his art was due to the fact that he was able to capture the charm of Penang through the depiction of local children at play. Hin Bus Station has also been a key community builder in creating the local artisan market which sees a myriad of oferings from crafts, to works of art to a diverse array of food ranging from cofee to oysters!. Come weekends, the place is flled with families and individuals who come to partake in the lively atmosphere and to mix with fellow creatives or be inspired by the creativity that is on display.

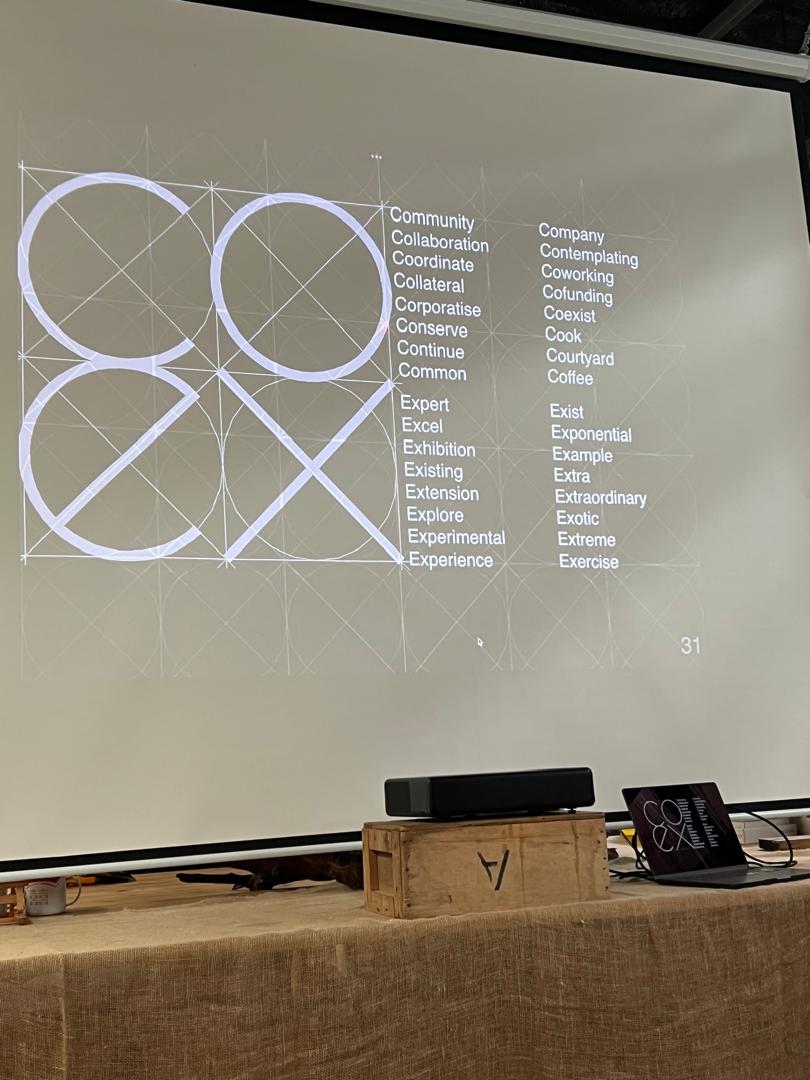

Credit is due to them for the fact that they were able to survive despite the Covid lockdown and now 12 years on, they have emerged stronger than ever through the brilliant collaboration with architect Mei Chee Seong to create Co-Ex an adjacent space which was built on an old scrap yard. Most of the material used has been recycled from either the yard or sourced within Penang.

Mei is what one would term a modern “junzi” 君子—an accomplished gentleman who embodies the Confucian ideals of wisdom, integrity, respect, self-cultivation (a commitment to learning) and a skill in the four arts which in those times meant playing an instrument (qin), playing go, calligraphy and painting.

This glimpse into Mei's character perhaps provides us with a clue to the philosophy of COEX which serves to bring together Community and Experiences, Collaborations and Exchanges, Co-design and Experts and so on.

Co-Ex houses Mei's architectural practice as well as his watercolour paintings. Once a day, he has been known to demonstrate his cofee knowledge by serving his guests with hand poured cofee he has roasted.

He and his team also curates a whole host of programmes that builds communities—from black and white Cantonese movie nights for the elderly community, to dances, to live indie music performances.

COEX also houses amongst others, a cofee shop, an incense shop, a heritage ceramic shop and a bookshop.

In placemaking, partnerships and collaborations are deemed crucial for bonding and success. Thus, these two collaborations between COEX and Hin Bus have created another layer of ofering for the community at large as well as paying customers—a win-win for all.

COEX

Kuala Lumpur

After their successful grant programme in George Town, Think City was tasked by Khazanah to expand to Kuala Lumpur (KL) in 2015. The heritage core of KL was rapidly hollowing out and local residents and business owners started to leave the city for newer suburbs. The fnancial district which was primarily located there wasere also set to relocate to the new hub called TRX located roughly 4.7km away. This vacuum was flled by an infux of male- only migrant residents and businesses. Although the migrant community provided a diferent vibrancy, it was however at the expense of diversity. The shops and services ofered in the city were only catering to one group of residents to with the exclusion of many locals still living and working there, and foreign visitors. Thus Think City used placemaking as a tool to entice locals back by adding some diversity back into a once thriving area.

Working together with the City Hall of KL (DBKL), Think City started to transform small pockets of spaces into mini gardens and cultural spaces to create a level of excitement back into the city. In 2014, Think City signed a Memorandum of Understand (MOU) with PPS and the event was graced by Fred Kent. This MOU led to a series of mentorships and workshops by PPS and, many of these initiatives were guided to some extent by PPS' Lighter, Quicker and Cheaper (LQC) approach.

Think City transformed spaces into pocket parks and exhibition spaces—Medan Pasar, the site of KL's frst wet market, was transformed into a micro housing exhibition space during the World Urban Forum in Feb 2018. Two micro houses were built on the square to address the lack of housing issue in the heritage core of the city centre. One micro house built by Think City was designed by Tetawowe Architects and incorporated the use of sustainable materials such as recycled UHT boxes for the external walls and roof. Whilst the other micro house built by DBKL showcased how one could ft micro apartments into abandoned buildings. DBKL and Think City also collaborated on rejuvenating an old fountain with the help of Ng Seksan to an urban oasis. To attract more visitors back into KL, DBKL also started to close roads to facilitate a food market in front of the Sultan Abdul Samad building on Jalan Raja, one of the most iconic streets of KL.

Another LQC approach that became a mainstay, was to transform the Masjid Jamek Light Rail Transit (LRT) station into a performing and visual art space through the “Arts On the Move” programme which ran from 2017-2019 and rebooted in 2023, making it the world's longest curated performing and visual arts programme in a transit station. The key criteria for the curation was—it had to have 90% local content and artists. Within that 90%, there would be some heritage components in the performance thus ensuring the continuation of local art forms such as dikir barat, Chinese Opera, Malay, Chinese, Indian and East Malaysian traditional dances. These were juxtaposed with contemporary art forms such as doodling, live contemporary drawing and place-based photography to ensure relevancy amongst the younger audience. Another success story for placemaking is the creation of the Entrepreneur Matching Grant which seeded places like Zhongshan Creative Hub in Kampung Attap and Kwai Chai Hong in Chinatown.

Of the two, Zhongshan is my favourite as the building itself has great character and the curation of the place done artfully by Liza Ho, has managed to retain the building's charming yet quirky charac-ter. Since its launch in 2018, it has retained 100% occupancy and has expanded into another building called the Zhongshan Annex. Both the original building and the annex is home to 2 record shops (one for hip hop lovers and the other for punk rock afcionados), one lifestyle beauty/wellness store, a bespoke stationary store, a sourdough bakery and restaurant, 2 restaurants and a bar, a bespoke tailor, a design archive, two design consultancies, a community library, two fne artists' studios, a recording artist's studio and a lawyer's ofce. And of course, there is a quaint little nook which has my favourite cofee corner called Piu Piu Piu Café and an art gallery called The Back Room.

This together with quarterly festivals and parties, creates a great place where the young, hip and the slightly alternative crowd can ‘hang'.

Kuala Lumpur 2014 – Space Use disparity

Arts on the Move — Live Drawing

Arts on the Move Doodle

Arts on the Move Dikir Barat Performance Think City. Photo by Susie Kukathas

Zhongshan exterior

Zhongshan-Central Spine

Bangsar — A Case Study

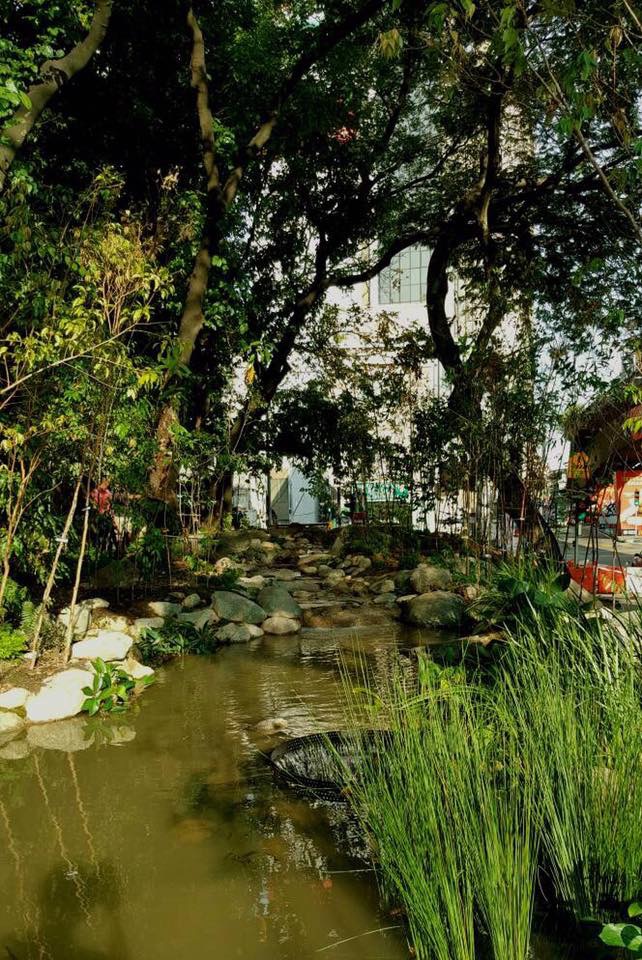

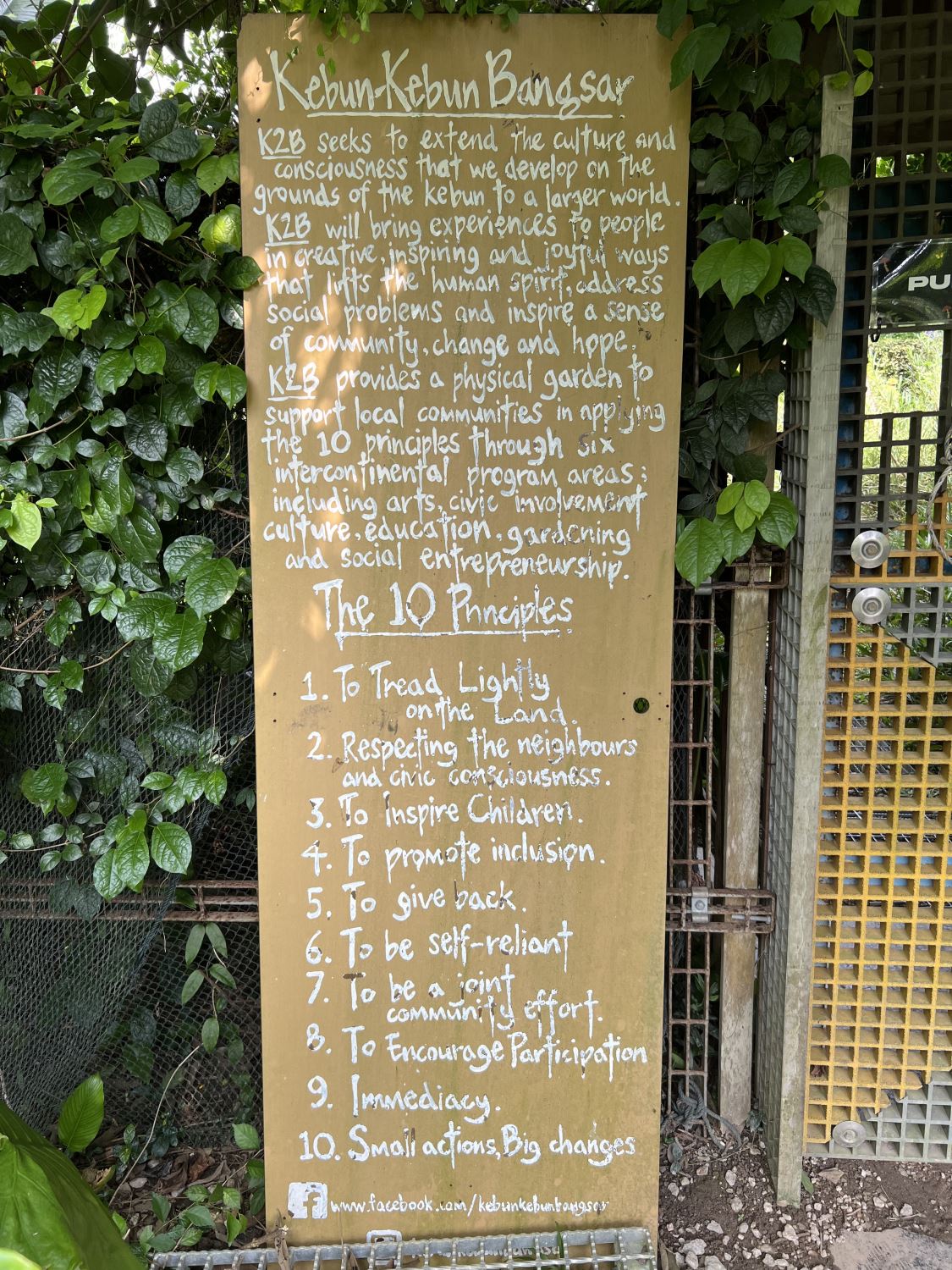

It would be remiss of me not to mention two successful placemaking projects in the upscale suburb of Bangsar, Kuala Lumpur. One project was Kebun Kebun Bangsar (KKB) which is an urban farm and garden situated beneath the electricity pylons. The brainchild of Ng Seksan, a renowned landscape architect who wanted to increase the availability of public spaces. This 7-acre garden was given a Think City grant and opened in 2018 and within a few years was self-sustaining. One of the keys to their success was the cows who were brought in to maintain the grass and provide fertiliser. These cows helped KKB cut its operating costs by ¾ enabling it to thrive utilising the permaculture farming method. The farm with its refugee running vegetable plots and education programmes, has been amazingly successful and has inspired a few others to start their own initiative. In 2023, Garden Futures selected KKB as one of six extraordinary gardens of the world6.

APW in Bangsar is also a noteworthy mention. A former printing factory turned into a creative campus full of eateries, creative outlets and ofces. Here contemporary architects in Malaysia such as Studio Bikin and POW Studio are reimagining traditional design principles to create spaces that resonate with modern sensibilities while staying rooted in cultural heritage.

Helmed by Ee Soon Wei, APW has gone through a few iterations. The frst consisted of a few large restaurants, ofces and a co-working space. The pandemic created the need for another rethink as co-working was eschewed in favour of Working from Home. The latest iteration, with smaller shops, I feel is the best one yet. In 2024, APW gain international recognition with the opening of the Coach experience store and café. This Coach concept store is one of the kind in Asia and the frst to be located in a non-mall premise. In a lovely nod to APW, Coach has embedded the history of APW into its store display, providing context to both their shared history and love of their craft.

Kebun Kebun Bangsar

APW after Rejuvenation

Ipoh

Ipoh old town has been going through a resurgence in the last decade. It is a charming town which was the centre for tin mining and slowly lost its allure when the mines closed and the call of KL and Penang became too enticing for the young.

However, Ipoh now has a whole host of placemakers hoping to put their home back on the map. There is an organisation called P-Lab led by Chok Yen Hau that looks at bringing to light all that is charming in secondary cities.

Chok, a former journalist, took his fascination for stories to the next step. Instead of just writing about people and places, he decided to form PLab, relocate his whole family to Ipoh, to see what would happen if he curated experiences instead. In his journey, he was deeply inspired by Ho Pei Chun from Skyyard, one of Taiwan's most beautiful homestays. Ho's placemaking method of discovering the special elements that made up the DNA of the place and then put them all together in a series of programmes or collaborations to create something magical where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Chok then spent his time discovering the artisans and the cultural leaders in Ipoh and helped create awareness for their products or their businesses.

Inspired by Ho, one of Chok's frst projects was putting together an organic farmer called Ah Niao, together with Vooi Yam, a potter, and Sam who has worked at a Michelin star restaurant in the United Kingdom. Together they created a dining experience that touched a Taiwanese journalist who then wrote an article about her Ipoh experience. Buoyed by this, Chok began to put together more collaborations by focusing on visits to local operators across various industries, including traditional trades, artisanal crafts, and other community-based businesses. In the 7 years he and his team have created what he terms as Impact tourism where customized tours for placemaking teams and University Social Responsibility (USR) teams are designed so that the local to global theme can spread.

_jpg%20Industry%20Guidance%20by%20PLAb.jpg)

_jpg%20PLab%20event%20Pic%20by%20P%20Lab.jpg)

%20_jpg%20Industry%20Guidance_Bird%20Farm%20PLab.jpg)

Chok Yen Hau and Photos of Community events and Community Artisans courtesy of PLab

Conclusion

Malaysia is a place where placemakers thrive. Its richness and unique sense of place is woven from the interplay of cultures, histories, and traditions that have shaped its identity. Whether it is a Malaysian rejuvenating a heritage enclave, opening a scone shop in Ipoh or an upscale laksa store in KL, true Malaysian placemaking goes beyond physical design—it captures the soul of our shared heritage, where diversity is not just acknowledged but celebrated as the very essence of belonging.

To design places that encapsulate this whilst allowing room for other cultures is the epitome of being Malaysian. Afterall, we have been opening our doors to welcome the world since the 15th century. Being open, warm and welcoming are quintessential Malaysian traits that entice talents to stay or attracts them to relocate here.

The concept of Malaysian-ness is thus, to honour this living and ever evolving tapestry. It means crafting places that invite shared experiences, refect multicultural narratives, and foster organic connections—because in Malaysia, place is not just where we are, but who we are together.

Coach at APW

World Urban Forum 2019 - Water based garden for the Micro houses

Medan Pasar WUF9 Micro Houses and Greening the Square

Medan Pasar WUF9 Micro House and Greening the Square

Footnotes

1. Parameswara (1344 – c. 1414), thought to be the same person named in the Malay Annals as Iskandar Shah, was the last king of Singapura and the founder of Malacca. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parameswara_of_Malacca

2. The Peranakan Chinese are an ethnic group defned by their genealogical descent from the frst waves of Southern Chinese settlers to maritime Southeast Asia. The Peranakan Chinese are often simply referred to as the Peranakans.[a][6] Peranakan culture, especially in the dominant Peranakan centres of Malacca, Singapore, Penang, Phuket, and Tangerang, is characterized by its unique hybridization of ancient Chinese culture with the local cultures of the Nusantara region, the result of a centuries-long history of transculturation and interracial marriage. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peranakan_Chinese

3. William H. (Holly) Whyte (1917-1999) is the mentor of Project for Public Spaces because of his seminal work in the study of human behavior in urban settings. While working with the New York City Planning Commission in 1969, Whyte began to wonder how newly planned city spaces were actually working out—something that no one had previously researched. This curiosity led to the Street Life Project, a pioneering study of pedestrian behavior and city dynamics. Source: https://www.pps.org/article/Wwhyte

4. Fred Kent, founder and former president of Project for Public Spaces, speaks widely on public spaces and placemaking, and is working on two placemaking initiatives—The Social Life Project and PlacemakingX. He is a leading authority on revitalizing city spaces and one of the foremost thinkers in livability, smart growth and the future of the city. Source: https://www.pps.org/people/fkent

5. Source: https://www.pps.org/article/wwhyte

6. See https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20230505-fve-extraordinary-gardens-around-the-world

loading......

loading......