Author

Ronald C. T. LIM, Image captions, credits & sources in table below this essay

Ar. Ronald C. T. Lim is a Singapore-licensed architect and design educator who works at the intersection of architectural culture, design research and practice. He has worked internationally for distinguished architects like Cesar Pelli and Fumihiko Maki and more recently, collaborated with Lekker Architects on groundbreaking design research. He also curated the frst major retrospective exhibition for the newly launched Singapore Architecture Collection, "To Draw An Idea: Retracing the Designs of William Lim Associates / W Architects". Besides running his eponymous practice Ronald Lim Architect, Ar. Lim was also Co-Chief Editor of The Singapore Architect magazine and currently teaches at the National University of Singapore. He holds a Master of Architecture from Yale University.

Depending on who one speaks to, the city-state of Singapore conjures different images, impressions and meanings, which then frame and colour differing perceptions of its architecture. For an international audience, the prevalent image is likely that of a technological utopia humming with technocratic effciency. Record numbers of international visitors (some 16.5 million in 2024) throng this global business city whose sparkling skyline of gleaming skyscrapers and the decade-old Marina Bay Sands (MBS) continue to defne brand Singapore, the technotopia. This icon-flled skyline, itself the handiwork of generations of urban planners at the nation's Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), glitters as demonstration of a Singaporean exceptionalism stemming from global capitalism.

Yet, this ubiquitous image of a global city par excellence illustrates but one outer facet of the polity's many simultaneous, overlapping realities. As a multicultural city-state with a polyglot society of diverse origins, special effort is made to weave and coax a common national experience in the everyday such that this diverse society also identifes itself as one people. Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore's founding prime minister, often proclaimed, "To understand Singapore and why it is what it is, you've got to start off with the fact that it's not supposed to exist and cannot exist … we don't have the ingredients of a nation, the elementary factors: a homogenous population, common language, common culture and common destiny." Therefore, beginning with policy and extending to the built environment, the Singapore government exerts every effort to create the common, accessible spaces and amenities that defne the common Singaporean lived experience. Notwithstanding the many options for outlandish Crazy Rich Asian luxury that entices Asian billionaires to park their wealth on the island, the large majority of everyday Singaporeans reside in large, heterogenous neighbourhoods that were planned and constructed by the state where public housing, neighbourhood retail and recreation co-exist with private condominiums for the upper middle-class.

To perceive and understand Singapore's architecture and urbanism only through an icon-studded, global neo-liberal gaze misses most of the plot behind Singapore's ongoing social and national construction that extends into built form and space. Charles Jenck's 2016 essay in the Architectural Review "Notopia: the Singapore paradox and the style of generic individualism" represents one such predictable, if unfortunate, surface-reading of cherry-picked icons from a Western gaze. Unlike the glitzy Middle-Eastern counterparts of Dubai or Doha with their predominantly expatriate population, the project of Singapore (the national polity, the city, the society, the economy) is a game of high-wire balancing between multifarious needs, desires and imperatives that are sometimes inherently confictual.

Big-ticket superlative projects built for next-generation economic relevance (e.g. a massive new airport terminal, a new megaport that will be the world's largest container terminal, a new state-of-the-art entertainment arena) are counter-balanced with massive investments in social infrastructure (e.g. housing, education, healthcare, recreation) that fulfls the social compact between the state and its populace. In this arrangement, the state becomes a major provider and remediator of the socio-economic tensions latent in neo-liberal capitalism. Where economic growth alone cannot lift the tide for the population's more vulnerable segments, the state invests heavily in neighbourhood and other social support infrastructure to level the playing feld. Political elections every fve years are, in essence, a referendum on the ruling party's effectiveness in remediating these tensions. The spectacularity of Moshe Safdie's donut-shaped Changi Jewel, featuring the world's tallest indoor waterfall encircled by a forested terrace, may captivate and dazzle visiting travellers with its sensorial biophilia. Yet, for every attention-grabbing structure designed for global Instagram-mability, there exist many other less publicised but equally fascinating permu-tations of social typology that are trans-forming the fabric of everyday life for the Singaporean heartlander. Integrated complexes like Our Tampines Hub – a gleaming community complex on a 5.3-hectare site integrating a library, swimming complex, stadium, neighbour-hood retail, community centre and seam-lessly plugged into transit – are turbo-charging community life in Singapore's public housing New Towns. Extrapolating the Modernist maxim "form follows function" and its capitalist counter-part "form follows fnance," in Singapore both function and fnance follow policy, which indelibly shapes its architecture. One can say, "Form follows policy."

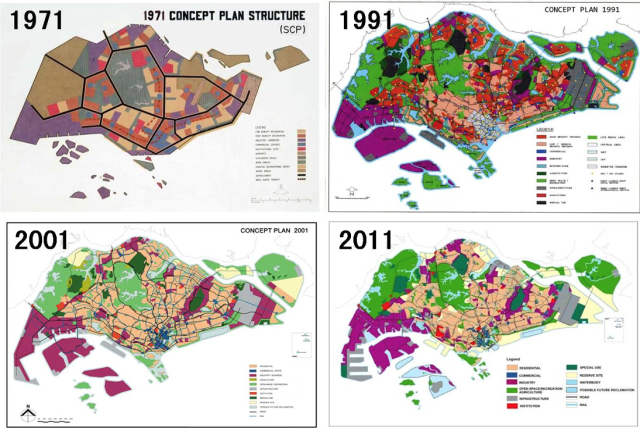

Urban Densifcation and Regulatory Form

At the time of Singapore's independence in 1965, her population was hardly 2.5 million. This fgure has since swelled to over 6 million people today. With a land area of 735 square km (i.e. just 1/3 the area of metropolitan Tokyo) and with over a third of her land reclaimed from the sea, securing possibilities for the city-state's future development requires a rigorous methodical approach to shape the urban policies and regulations that can, at times, seem unrelenting. Every 10 years or so, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) systematically reviews and updates Singapore's Concept Master Plan, setting out the broad brushstrokes for the next 30 to 50 years of its development. This eventually cascades down to operationalised control parameters like plot ratios, building setbacks, and urban design guidelines to control massing bulk, which then guides subsequent building development on individual sites.

Singapore's offcial "Land-Use Intensifcation" policy encourages redevelopment with a higher built density as a precondition for lease renewal, where most properties are on an expiring 99-year lease. This adds impetus to a brownfeld demolish-and-rebuild dynamic where buildings inevitably get bigger, taller and more complex. Once-standalone amenities like the polyclinic, the school or the community centre are now combined into mix-and-match permutations of dense, one-stop urban typologies located on superblock land parcels. Kampung Admiralty, a WoHa-designed complex integrates senior-friendly apartments with a rooftop park, medical centre, hawker centre and neighbourhood retail. Other densifcation examples are less mixed and more consolidative like Eunoia Junior College, a 10-storey junior college (i.e. high school) campus complex with a massive elevated stadium deck or the many 50-storey public housing complexes woven with landscaped community decks currently under construction. Whether for hospitals, schools or other amenities, integrated mega-consolidation yields impact at scale. Land has become too precious and expensive for what used to be modest, standalone buildings. In this high-density "land-use intensifed" Singapore, new small-to-mid-sized building developments that conjure intimacy, human scale and urban fabric will become increasingly rare.

For the URA and its sister agencies like the Building & Construction Authority (BCA) and the National Parks Board (NParks), a plethora of regulations and incentives attempt to coax outcomes that the state perceives as positive for the built environment and its ecosystem. Of this smorgasbord of carrots and sticks, URA's defnition of gross foor area (GFA) or conditions for when it grants a project "bonus GFA" is a most powerful incentive tool for private developers. Exempting certain desired spaces like communal sky terraces from GFA calculation incentivise developers (who seek to maximise rentable area) to provide these features that they would otherwise exclude. URA considers granting bonus GFA in other circumstances if the developer offers a public good encouraged by the state – like providing community amenities, conserving an adjoining heritage structure, installing public art, using district cooling, etc. As an accompaniment, BCA uses its "Buildability Score" requirement to incentivise the adoption of precast and prefabricated technology that reduce reliance on construction labour.

These KPI-induced state regulatory levers have exerted an indelible imprint on the built environment. The myriad towers with sky terraces, constructed biophilia, examples of lego construction with high repeat factors, and mass-engineered timber buildings point to the state's success in translating its objectives into tangible outcomes, ranging in aesthetic results from the compelling to the outright drab-and-ugly. For the everyday practising architect in Singapore, navigating the overlapping regulatory frameworks of different agencies with their own mandates and self-perpetuating KPIs is no simple walk in the park. While they illustrate effective policy implementation, there is a growing tendency among local architects of "designing to the regulation" (much like how its students "study to the examination syllabus"). In a competitive economic milieu of trim margins where "fee burn" is an ever-present reality, the appetite for bottom-up critical design responses that do not dovetail neatly into these state-defned regulatory frameworks has narrowed. Within this highly regulated landscape, the basic organising diagram for each building varies and differentiates within a narrow latitude. In Singapore, form follows regulatory parameters to a T.

Institutionalising Urban Biophilia

In recent years, the image of buildings draped in luxuriant tropical greenery growing from architectural planters or on vegetated screens on a building's facade has become synonymous with the architectural brand of Singapore. The earliest such examples of such architecture were introduced to Singapore in the 1980s by the Honolulu-based frm Wimberly, Whisenand, Allison, Tong & Goo, which designed The Arcadia condominium (1984) and the Garden Wing of the Shangri-La Hotel (1985). These early examples sold a romantic narrative of luxuriant tropical gardens amidst generous built form, and the approach was further developed into a theoretical urban agenda in the following decades, most notably with pioneer architect Tay Kheng Soon's treatise "Megacities in the Tropics" (published in 1989) and his proposal for Kampung Bugis Development Guide Plan (c. 1990) where urban typologies would offer vegetated green relief at a large scale. Within two decades, the frst architectural realisations of these high-density verdant typologies would be completed by WoHa Architects – notably Newton Suites condominium (2008) and its School of the Arts (2008).

As a natural outcome, the state's regulations have caught up to further institutionalise and systematise these developments. One unique metric is the "green replacement ratio," a metric originally developed internally by WoHa Architects to prove that new building projects can compensate, or even multiply, displaced surface vegetation on the original building site. Specifc proof-of-concept projects like their much publicised Parkroyal Pickering Hotel (2013) and Oasia Hotel Downtown (2016) proved that their buildings can achieve "green replacement" ratios of anywhere between 2 and 9. These projects have given URA the confdence to institutionalise the metric, setting minimum requirements for planted surfaces on new buildings and also as a yardstick for other GFA incentives. This has led to widespread adoption and normalisation of constructed biophilia in private sector projects.

On an ever-heating planet where Singapore's tropical climate is not invulnerable to the effects of global warming, greenery is increasingly deployed as a technique to mitigate a rise in ambient temperatures. For buildings at an architectural scale, vegetated surfaces help to mitigate heat through latent heat of evaporation and covering surfaces otherwise exposed to the sun, helping to moderate air-conditioning loads. These plantings often fank naturally-ventilated communal or circulation spaces. WoHa's recently-completed BRAC university in Dhaka, Bangladesh suggest that this model of climatically-adapted high-density urbanism is starting to be exported to the global south. Beyond visual rhetoric, the benefts of constructed biophilia are real and measurable. Nevertheless, the glib tendency of couching such greenery-draped biophilic buildings as "sustainable" masks the inconvenient truth of the amount of embodied carbon involved in constructing (in concrete) the hard structures to begin with, not to mention the costs of initial demolition. This conversation is only starting to surface within the state's regulatory body politic.A major complement to the above "systematised biophilia" is the spatial typology of the Sky Garden, a key architectural feature in high-rise towers in Singapore (both commercial and residential) that is highly-encouraged by URA through GFA-exemption. These are essentially communal, airy landscaped decks located on a tower's intermediate foors or upper foors, offering gathering spaces with panoramic views. These spaces have proliferated, becoming a normal feature in many commercial and residential towers. A few noteworthy projects meaningfully expand this lexicon to push the boundaries of possibility. BIG's Capitaspring Tower, connected four skygarden foors sectionally to create a mid-tower neighbourhood of restaurants and lifestyle offerings. The Oliv by W Architects, a mid-rise residential tower, fronted each duplex unit with a sky terrace to extend each apartment's private domain, reconvening the feel of a villa.

Resetting Public Housing & Neighbourhood Centres

With one of the highest home-ownership rates in the world, over 80% of Singapore's population live in the city-state's public housing estates. This represents a large swathe of the local population, covering the lower-income to the upper-middle income brackets. As a side anecdote, cars of luxury makes are not an uncommon sight in public housing estates. Relative to free-market-priced private condominiums, restrictions on the public housing market have kept these apartments within a relative range of affordability unseen in other global cities like Hong Kong, London, and New York where home ownership is out of reach for many. In Singapore, preserving citizens' access to affordable housing remains a cornerstone of electoral legitimacy for the ruling party, and this topic remains a hot-button issue at every election. A generation ago, the government sold the concept of public housing as an appreciating asset that made citizens wealthier. Today, this same asset appreciation has raised barriers to ownership for young couples and families, requiring the government to double-down on responding to their aspirations and needs.

Whereas the earliest objective of public housing was the renewal and resettlement of slums (c. 1960s to 1970s), this subsequently evolved to the encouragement of community identity and social mixing (c. 1990s onwards). Beginning with the high-profle Pinnacle@Duxton by ArcStudio (2008), Singapore's frst high-density 50-storey residential complex, successor iterations of public housing have consolidated to higher densities and included a higher design component – all while maintaining affordability, economy, and the standardisation factor that precast construction demands. The Pinnacle's successors, Skyville@Dawson (2015, WoHa Architects) and Skyterrace@Dawson (2015, SCDA Architects) further evolved the typology with explorations of the spatial and visual languages possible in standardised 50-storey towers where painted concrete is the primary means of material expression. Skyville@Dawson, in particular, broke the complex's scale down into sub-neighbourhood units (what it calls "sky villages") – each with its own community terrace. This typological evolution continues to this day. Skyresidence@Dawson (c. 2023, Surbana Jurong), while architecturally less refned than its predecessors, features syncopated tower heights in a searching balance between form, urban density and height. The complex wraps around a conserved 1950s market that has been adaptively-reused into a new lifestyle hub.

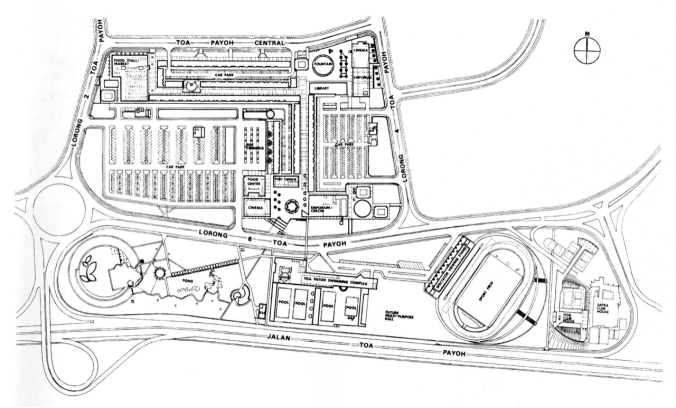

When the Housing & Development Board (HDB) planned the city-state's frst New Towns in the 1960s and 70s, the nucleus of each satellite town was the neighbourhood centre. Within these planned amenity centres, generous pedestrian plazas would link community shops with a wet market, polyclinic, library, cinema, bus terminal and other such facilities, adapting from the model of British New Towns like Milton Keynes. With four decades of subsequent population growth and infrastructural development, a new level of intensity percolates these town centres now served by Mass Rapid Transit. The land in these town centres is now precious, valuable, and re-developable. This has led to a level of spatial reconsolidation that is happening in many of Singapore's "mature estates." New "neighbourhood hubs" built at a higher density, consolidating once-standalone amenities into various programmatic permutations, are being planned and built across Singapore with the objective of freeing land once occupied by the older amenities for other strategic or rentable uses.

One of the earlier test beds of this hub concept is Our Tampines Hub (2017, DP Architects), a massive community complex that serves as a one-stop-shop of civic, recreational, institutional and public service functions – hosting government offces, a hawker centre, stadium, library, swimming complex, community auditorium and other functions. Underlying this project was the state's pitch for a holistic "whole-of-government" experience that breaks down the silomentality inherent in the bureaucracy of government agencies. Other such hubs feature different programmatic permutations. Kampung Admiralty (2018, WoHa Architects) is pitched as an elder-friendly development, combining senior-friendly apartments with a polyclinic, food centre, neighbourhood retail, and a sheltered community plaza linked seamlessly with mass transit. In the singular Oasis Terraces (2019, Serie Architects), the programming is predominantly shops accompanied by a polyclinic and blended with a massive ramped rooftop community park. The most recent of these neighbourhood hubs, the sports-oriented Bukit Canberra (2022, DP Architects) pitches a narrative of regenerative ecology through planted biophilia over contiguous hexagonal units that blur the distinction between indoor and outdoor.

Among the frst "net zero" energy buildings to be built in Singapore is SDE4 at the National University of Singapore (2019, Serie Architects). This building tackles operational carbon, combining passive design strategies with photo-voltaic panels and a hybrid-cooling system that allows it to consume less energy than it produces. The adjacent SDE1 and SDE3 buildings, whose renovation and adaptive re-use was undertaken by Pencil Design (a design practice led by NUS professor Erik l'Heureux) start to shift the focus from operational to embodied carbon. The extensive, yet sensitive, remodelling proved that 40-year-old buildings constructed for an earlier era could be "updated" and made more attractive without needless demolition before the end of a building's life-cycle. Pencil Design's recently-completed remodelling of Yusof Ishak House, a legacy student amenity centre at NUS, are another example of the aesthetic and formal possibilities of low-embodied-carbon adaptive re-use.

Adaptive Re-use and Carbon Responsibility

As a low-lying coastal city-state, Singapore is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The government has thus set out an aggressive agenda to half carbon emissions from its peak by 2050 to fulfl its international treaty obligations under the Paris Agreement, notwithstanding the city-state's high dependence on important natural gas for its electricity needs with few renewable alternatives. For context, the ubiquitous solar panels installed all over Singapore contribute less than 1% to Singapore's total energy mix. With the built environment responsible for about 40% of the world's carbon emissions, the imperative to do more is high. Of specifc note is the distinction between "operational carbon" (energy used to operate the building) and "embodied carbon" (energy consumed to construct the building).

In terms of operational carbon, the city-state has made steady progress. The Building & Construction Authority (BCA)'s Greenmark certifcation programme, in place for 20 years, has steadily advanced the agenda and imperative for energy-effcient buildings. Even in air-conditioned tropical Singapore, consensus on the imperative for passive design strategies to mitigate heat gain and unconscionable energy loads for air-conditioning has grown. Where embodied carbon is concerned, however, the carbon costs of the island's wanton demolition and redevelopment are still not captured in a regulatory system of accountability or disincentive. Unfortunately in Singapore, the tendency to demolish buildings before the end of their life-cycle instead of adaptively re-using them proceeds with general impunity.

Among the frst "net zero" energy buildings to be built in Singapore is SDE4 at the National University of Singapore (2019, Serie Architects). This building tackles operational carbon, combining passive design strategies with photo-voltaic panels and a hybrid-cooling system that allows it to consume less energy than it produces. The adjacent SDE1 and SDE3 buildings, whose renovation and adaptive re-use was undertaken by Pencil Design (a design practice led by NUS professor Erik l'Heureux) start to shift the focus from operational to embodied carbon. The extensive, yet sensitive, remodelling proved that 40-year-old buildings constructed for an earlier era could be "updated" and made more attractive without needless demolition before the end of a building's life-cycle. Pencil Design's recently-completed remodelling of Yusof Ishak House, a legacy student amenity centre at NUS, are another example of the aesthetic and formal possibilities of low-embodied-carbon adaptive re-use.

The mindset of adaptive re-use has started to make its way to other community projects in Singapore. Many of these projects arose less from a sense of carbon responsibility and more from limited budgets that do not permit outright redevelopment. Nevertheless, they present positive test cases for how frugal resources can achieve exponential transformation when deployed intelligently and sensitively in an existing built structure. Of these, the most exemplary is the renovation and expansion of Delta Sports Complex (2023, Red Bean Architects). Originally built in 1979, the adaptive re-use saw an accretion of acupuncture stitches, surgical demolitions and design moves to breathe new life and circulation into the building, restoring its relevance and attractivity to the building's surrounding community.

There is a growing awareness that a template model for demolition and redevelopment would only result in more generic spaces devoid of identity, refective of the "tabula rasa" critique frst refected in Rem Koolhaas' 1996 text "The Singapore Songlines." As such, alternative bottom-up models of urban development are starting to emerge as proof-of-concept test cases. One such example is New Bahru, a new F&B lifestyle complex located at the 1960s-built Nan Chiau School campus originally designed by colonial-era architect James Ferrie. (2024, adaptive re-use by FARM). Developed by local hospitality group Lo & Behold Group which carries a series of unique restaurant brands, this complex offers a curated series of local boutique and restaurant brands, offering itself as a uniquely-authored counterpoint to the generic retail commercialism that pervades much of Singapore.

Conservation Meets Modernism

Relative to other countries and cities in the region, Singapore's conservation programme had an early start. In the late 1980s, after close to two decades of urban renewal that came at the expense of its vernacular and colonial built heritage, the URA launched Singapore's frst Conservation Master Plan to conserve entire districts of shophouses and other buildings of architectural or cultural merit. Almost forty years on, the conservation challenge has now turned to a different kind of "heritage" for which no systematic framework exists to protect this layer of history – that of Singapore's post-independence, modernist buildings that bore witness to the city-state's industrialisation.

Possibly the frst of these modernist buildings to be deemed nationally important was valorised too late. The groundbreaking Singapore Conference Hall designed in the 1960s by the pioneering Malayan Architects Co-Partnership was declared a national monument in 2010, only after it had been unsympathetically renovated a decade earlier to the disappointment of many. Over the subsequent decade, signifcant progress was made in the conservation and adaptive re-use of other state-owned landmarks like the brutalist Jurong Town Hall and Subordinate Courts (now redeveloped as the State Courts, Serie Architects, 2019). For such government buildings, conservation and responsible redevelopment was generally straightforward with the state being able to set a progressive example with the high-integrity conservation of these landmarks.A much bigger challenge lies with the many privately-owned buildings of cultural and architectural merit. The aforementioned state "land-use intensifcation" policy together with decaying leases and stratospheric land prices is placing immense pressure on many such buildings to be sold for redevelopment at a higher density. For their aging owners, many such properties have also grown expensive to maintain and repair. The frst signifcant landmark that fell prey to this dynamic was the brutalist Pearl Bank – a cylindrical-shaped residential tower built in the mid-1970s. Pearl Bank's demolition galvanised the formation of the modernist heritage advocacy group Docomomo's Singapore chapter, spawning more active documentation, public education and policy advocacy efforts.

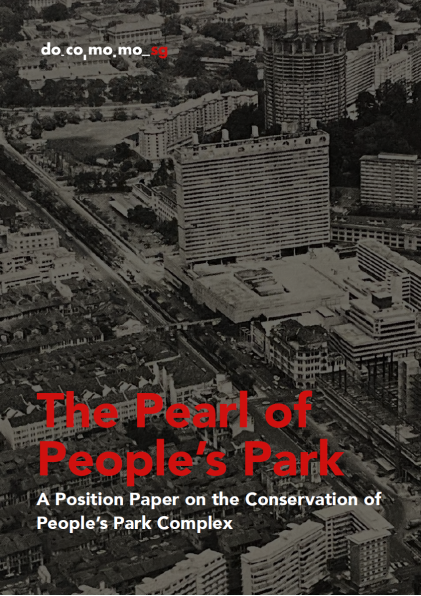

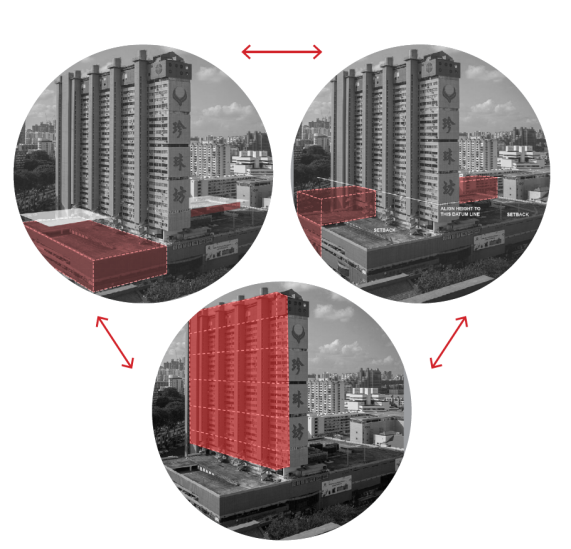

The lessons from Pearl Bank's demolition led to more robust efforts by both government and stakeholders to save these icons, culminating in the gazetting of the brutalist Golden Mile Complex in 2021 for conservation. As part of a quid pro quo, the URA offered generous GFA incentives to secure the building's business model. This complex's adaptive re-use and redevelopment is currently being led by DP Architects, with mixed reactions on the integrity of the fnal design. The cause of conserving and responsibly remodeling such modernist buildings continues to evolve as a work-in-progress. Docomomo SG's recently-published position paper on People's Park Complex (the sister building to Golden Mile Complex) simulated scenarios for responsible development, attempting to defne new paradigms for how such forms of conservation and adaptive re-use should proceed.

Paradigmatic Ethical Responses from the Next Generation

One of the unspoken challenges of the earlier mentioned consolidation towards larger-scale complexes and a track-record-based procurement system is that many younger practices in Singapore face increasing barriers to new building commissions, when compared to frms established a generation ago. The increasing cost of land and construction has also narrowed clients' appetite to take design risks in an expensive city-state where dollars-and-cents wield inordinate infuence over decision-making compared to visionary intent. This dynamic has led to most buildings in Singapore being maximalist permutations of effciency – including for small landed residential projects – where design authorship becomes secondary. Whereas an earlier generation of frms like WoHa started their practices with housing commissions as a testing-bed for theoretical ideas (e.g. tropical tectonics), today's young practices are relegated to pursuing tactical design opportunities within experiential interiors, limited-budget remodeling projects, and even paper speculations.

Nevertheless, this has not prevented younger architects from advancing new, ethical propositions in spatial design, expanding the scope of architectural practice beyond the conventional task of designing and erecting a building. Within the confnes of resource limitations, these practices are testing out new research-informed ethical paradigms (e.g. social inclusion, circular material ecologies) that were hitherto absent from local architectural discourse, refecting a growing diversity of design approaches. "Brick & Mortar Shop" (2021, L Architects) is an interior kitchen-appliance showroom that uses discarded "off-cut" stones and chip tiles with concrete hollow bricks to create a sensual tactile interior of material economy. Goy Architects is another practice that taps the potential of regional vernacular artisans to create sensitive, regionally-infected spaces celebrating the hand-made crafts and textures that resist the ubiquity of industrially-produced building products. Their Sukasantai Farmstay (2021) redeploys the simplicity of generous eaves in vernacular typology to create an understated farmstay resort that sits gently on its site, whose humble materials refect the indigenous Southeast Asian crafts in a contemporary way.

Another promising area of development is the realm of socially-inclusive design. Lurking beneath Singapore's growing prosperity, many ordinary citizens continue to face challenges in multifarious areas that defy the state's "one-size-fts-all" model of social services. Whether it be the challenge of raising an autistic or special-needs child, caring for a person-with-dementia in the family, or needing daycare for someone who is terminally-ill, the challenges faced by families-in-need can be daunting. The development of Singapore's social services sector supported by philanthropy has allowed it to fll in certain gaps and be stakeholder-partners to the government in providing support. In this realm, Lekker Architects has led on designing highly-nuanced, experiential interiors (or even speculative propositions) for users with various needs. "Quiet Room" at the National Museum of Singapore (2019) offers a soft, womb-like sensory "safe-space" for children on the ASD spectrum with sensory-processing disorders. They also designed "Kindle Garden" (2015), Singapore's frst inclusive pre-school where special-needs and "normal" children freely interact and learn together.

An Evolving Dynamic

The exigencies of a small global city-state needing to adapt and survive means that the city-state's neighbourhoods, spaces and showcase districts (and its governing urban policies) will continue to evolve and adapt to changing circumstances. As aforementioned, the project of Singapore (the national polity, the city, the society, the economy) is a high-wire balancing act between multifarious needs, desires and imperatives that are often inherently confictual. All of these coalesce to drive a dynamic – including an unrelenting pace of "rapid obsolescence" for recently-built buildings – that demands continuous renewal and redevelopment to maximise its limited land area. Singapore will forever be obliged to fnd imaginative ways to generate value for the economy while adapting to the demands of an ageing, heterogenous society that was "an accidental nation." This dynamic is unfolding in an era of unpredictability in the global trading system with existential consequences for this trade-reliant polity. As Singapore confronts this newly unstable world, the next chapter of Singapore's multi-act play is yet to be written.

Figures

The Singapore skyline.

Beyond the exclusive enclaves where Asia's wealthy elite reside (e.g. Sentosa Cove, image), the large majority of Singaporeans live in heterogenous neighbourhoods planned and constructed by the state, where public housing amenities co-exist with private condominiums. (e.g. Queenstown Estate, Singapore, image) Every efort is made to create the common, accessible spaces and amenities that defne the common Singaporean lived experience. (e.g. Ang Mo Kio Central, image)

Charles Jencks' 2016 essay "Notopia: the Singapore paradox and the style of Generic Individualism" myopically interpreted Singapore's architecture and urbanism through the lens of the authored "iconic building".

For every major big-ticket investment in Singapore's infrastructure to secure the country's future (e.g. Changi Airport Terminal 5, KPF & Heatherwick Studio), there are equivalent investments in social infrastructure like new housing estates (e.g. Tengah New Town, image below) and markets. (e.g. Jurong West Hawker Centre, by CSYA Studio)

Changi Jewel, an imaginative lifestyle complex located at Changi Airport, designed by Moshe Safdie.

Our Tampines Hub, a hub for integrated community, recreational and public services by DP Architects (2017).

The Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) updates its Master Plan of Singapore every 10 years or so, taking into account the nation's complex and evolving needs.

Kampung Admiralty, a WoHa-designed complex, integrates senior-friendly apartments with a rooftop park, medical centre, hawker centre and neighbourhood retail.

Eunoia Junior College, a new-generation "high-density" school typology with its elevated stadium and running track.

The Building & Construction Authority promotes the adoption of technology in new construction – like the use of volumetric construction (this image) and mass-engi of volumetric construction (this image) and mass-engineered timber.

Gaia@NTU, a mass-engineered timber building designed by Toyo Ito.

The Arcadia (1984) designed by the Hawaii firm Wimberly, Whisenand, Alison Tong & Goo was among the first buildings in Singapore to integrate greenery.

The idea of urban typologies planted with greenery was developed into a theoretical proposition by Tay Kheng Soon in his 1989 publication "Mega-Cities in the Tropics" and his proposal for Kampung Bugis Development Guide Plan in the same year.

Newton Suites by WoHa Architects. (c. 2007)

Parkroyal Pickering Hotel (2013) and Oasia Hotel Downtown (2016), designed by WoHa architects, attained "green replacement" ratios of between 2 and 9.

BRAC University by WoHa Architects in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

The Oliv by W Architects uses the sky terrace as a front for each duplex unit, reconvening the spatial feel of "villas in the sky"

The sky gardens in Capitaspring Tower by BIG (2021) are sectionally linked and programmed with restaurants and lifestyle amenities.

Pinnacle@Duxton (ArcStudio, 2008) was one of Singapore's first 50-storey high-density residential estates.

Skyville@Dawson (WoHa Architects, 2015) follows and improves on the model defined by Pinnacle@ Duxton.

Skyterrace@Dawson by SCDA Architects (c. 2015)

Skyresidence@Dawson (Surbana Jurong, 2023) with its syncopated heights.

Toa Payoh Town Centre in the early 1970s was planned as an amenity centre for Singapore's frst satellite housing township of Toa Payoh.

Toa Payoh Town Centre today at a higher built density.

Our Tampines Hub, the frst "whole-of-government" attempt to create a one-stop-shop of civic, recreational, institutional and public service functions.

Section of Kampung Admiralty showing integration of diferent community and age-friendly programmes.

Oasis Terraces: a retail, polyclinic and community complex in the Punggol neighbourhood by Serie Architects. (2019)

Bukit Canberra by DP Architects. (2022)

Enhancements to the original Ang Mo Kio Town Centre by Zarch Collaboratives.

The SDE4 Building at National University of Singapore, one of Singapore's frst Net Zero energy buildings, by Serie Architects.

SDE1 & SDE3 buildings at the National University of Singapore by Pencil Design, an adaptive re-use of 40-year-old campus buildings.

Yusof Ishak House, adaptive re-use design by Pencil Design.

Delta Sports Complex by Red Bean Architects. The project enhances its relevance to the surrounding community through selective stitching, minor demolition and additions to a complex built in 1979.

"The Singapore Songlines: Portrait of a Potemkin Metropolis … or Thirty Years of Tabula Rasa" in S,M,L,XL , a critique of Singapore's urbanism by Rem Koolhaas written 30 years ago.

New Bahru by FARM, c. 2024.

Singapore's conservation programme of its vernacular and colonial built heritage started early in the 1980s. Today's challenge is the fght to conserve its Modernist heritage.

The Singapore Conference Hall, designed by the Malayan Architects Co-Partnership (c.1965) was unsympathetically renovated before its gazetting as a national monument.

Jurong Town Hall, the frst of Singapore's post-independence buildings to be gazetted a national monument and restored.

Pearl Bank Apartments by Archurban Architects (c. 1976), since demolished.

Golden Mile Complex, the frst privately-owned post-independence structure to be gazetted for conservation, is being redeveloped. With additional GFA to make it commercially viable, the integrity of the original structure's massing is altered.

Docomomo SG's position paper on People's Park Complex builds on lessons learnt to anticipate "high-integrity" scenarios for the responsible redevelopment of the complex.

"Brick and Mortar Shop" by L Architects uses discarded "of-cut" stones and chip tiles with concrete hollow bricks to create a sensual tactile interior of material economy.

Sukasantai Farmstay by Goy Architects. The building redeploys the simplicity of generous eaves in vernacular regional architecture. It sits gently on its site, using humble materials that refect indigenous Southeast Asian crafts in a contemporary way.

"Quiet Room" at the National Museum of Singapore (Lekker Architects, 2019) ofers a soft, womb-like sensory "safe-space" for children on the ASD spectrum with sensory-processing

"Kindle Garden" (Lekker Architects, 2015) is Singapore's frst inclusive pre-school where special-needs and "normal" children freely interact and learn together.

loading......

loading......